- All Management Learning Resources

- Self-efficacy

Management summary

Over the past thirty years, there has been a large amount of empirical evidence to show that when employees feel confident in their abilities (self-efficacy), they are more likely to be effective performers. This CQ Dossier describes the concept of self-efficacy, describes how to measure the concept, and how to boost employees’ self-efficacy through leadership interventions. The CQ Dossier also describes the research showing the linkage between self-efficacy and job performance.

Contents

What is self-efficacy?

Self-efficacy refers to one’s belief in ability to carry out a series of behaviors in a specific domain (Bandura, 1982; 2001). Bandura proposed that self-efficacy enhances performance through increasing the difficulty of self-set goals.

Self-efficacy results in more challenging goals

Because the individual has set difficult goals, they tend to increase their effort and are more persistent over time (Bandura, 2012). The model proposes that because high self-efficacy results in more challenging goals, there is an improvement in performance because of the discrepancy between the individual’s current state and desired state (Bandura, 1982; 2001).

Self-efficacy can be seen as stable trait and as a situation-specific state

Self-efficacy has been depicted as both a stable trait and as a situation-specific state that varies across domains. Bandura (1982; 2001) stated that individuals acquire mastery in a limited number of domains; it would be unfeasible to acquire mastery in all aspects of human life.

For example, a professional might have a high degree of efficacy for financial management but low efficacy for counseling. However, it is also feasible to conceive of self-efficacy as a trait because an individual can show relative constant levels across a variety of domains (Eden, 1988).

How to measure self-efficacy?

Researchers have devised several scales to measure self-efficacy. Researchers use Likert scales including strongly disagree to strongly agree as anchors. However, Bandura (2012) proposed that self-efficacy should be measured with a unipolar scale ranging from no confidence to complete confidence.

Within work psychology, Eden has devised several measures of self-efficacy that have demonstrated reliability and validity and follow Bandura’s guidelines.

For example, in a study of special forces candidates, state self-efficacy was assessed through the candidates rating their competence to perform successfully in three career stages (Eden & Kinnar, 1991). The 10-point scale was anchored with “I completely lack the requisite ability”, and “I have the ability to do very well.”

Eden (1988) also proposed an additional way to measure state self-efficacy through comparative quantiles (e.g., quartiles, deciles, percentiles) that express expected success in terms of subjective social comparison so the frame of reference is the individual’s competence relative to peers.

The third method suggested by Eden (1988) is determined by asking employees how much output they expect to produce if they worked hard. In the study conducted with special forces, the candidates were asked to indicate the grade (from 0 to 100) that they expected to obtain in each career stage.

There are also measures of generalized self-efficacy whereby self-efficacy is conceived as being more trait than state-like. A popular self-efficacy scale by Scherer and colleagues (Scherer et al., 1982; 1983) includes items like “When I make plans, I am certain I can make them work” and “When I decide to do something, I go right to work on it” using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

How to influence and build self-efficacy

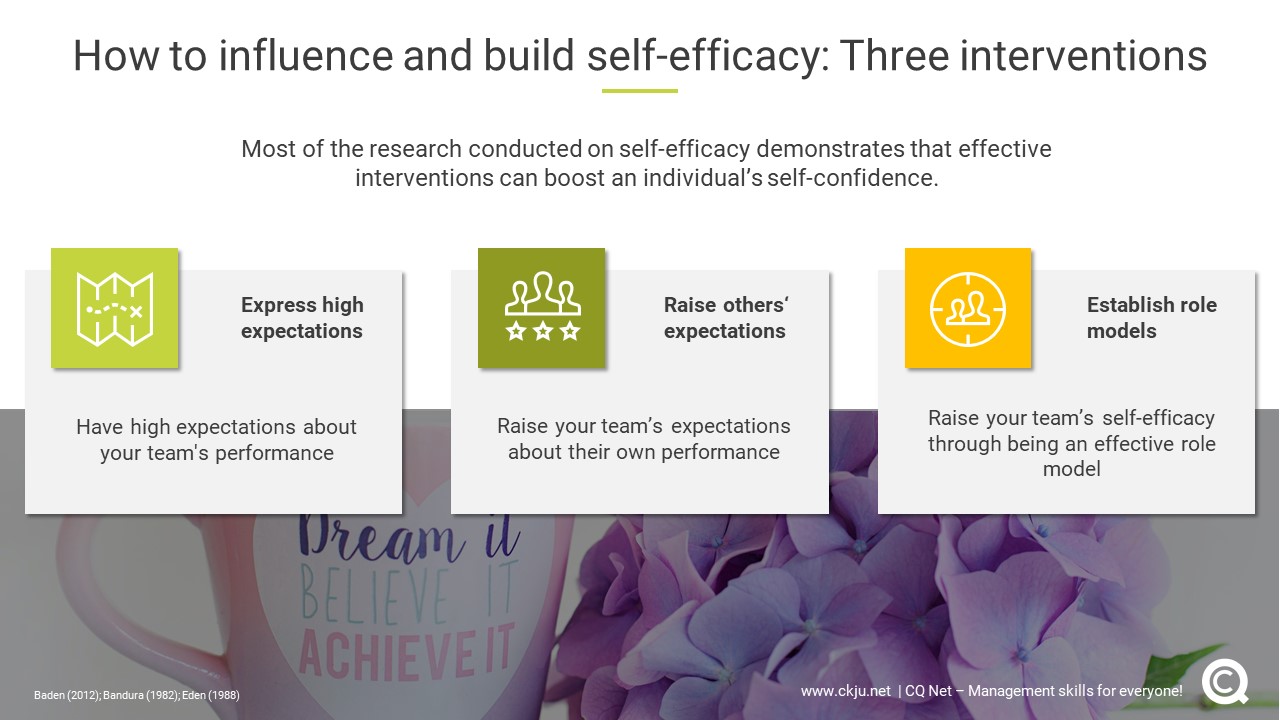

Most of the research conducted on self-efficacy demonstrates that effective interventions can boost an individual’s self-confidence.

The Pygmalion Effect: Express high expectations

One of the most ways to influence self-efficacy is through utilizing the Pygmalion Effect. The Pygmalion effect occurs when managers have high expectations about their subordinates’ performance; these high expectations result in subordinates increasing their work effort and performance (Eden, 1990).

The Galatea Effect: Raise subordinates’ expectations

The Galatea Effect also boosts self-efficacy through raising subordinates’ expectations about their own performance. The Galatea effect can occur independently of the manager so can be useful in some situations where the employee doesn’t have a manager.

Social learning: Establish role models

Bandura demonstrated that self-efficacy can be increased through effective use of role models (Bandura, 1982). In fact, social learning theory shows that self-confidence develops vicariously through social learning. Managers can raise subordinates’ self-efficacy through being effective role models.

In an intriguing study on ethics, business students were exposed to role models of social entrepreneurs; those who were inspired expressed an intention to be like the entrepreneurs in their future business careers. There was also a boost to self-efficacy in the students’ belief that they could be ethical in business (Baden, 2012).

Self-efficacy and job performance

Empirical research has found positive relationships between self-efficacy and job performance. In fact, over 93% of research studies have found positive correlations between self-efficacy and performance and boosts in self-efficacy (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998).

However, there have been questions raised recently about whether past performance increases self-efficacy rather than self-efficacy increases performance (Sitzmann and Yeo 2013).

Self-efficacy is related to job performance in between-groups studies

In the meta-analysis performed by Stajkovic and Luthans (1998) boosts to self-efficacy increased performance by 28%. When compared to other interventions such as goal setting, feedback and behavior change, the boost to self-efficacy was the strongest (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Another meta-analysis also found that the majority of studies revealed positive relationships between self-efficacy and performance (Sitzmann & Ely, 2011).

Recent findings suggest past performance drives self-efficacy

However, these meta-analytic reviews found positive relationships between self-efficacy and performance for between-groups studies. A recent meta-analysis by Sitzmann and Yeo (2013) found no relationship between self-efficacy and performance for within-subject designs. Sitzmann and Yeo (2013) suggest that their findings reflect the idea that it is past performance that boosts self-efficacy rather than self-efficacy boosting performance.

Leadership interventions to increase self-efficacy

The majority of research suggests that leaders can boost self-efficacy through showing confidence in their subordinates’ ability to perform well (Tims et al., 2011). One of the most effective interventions is through ensuring that leaders themselves are effective in motivating and boosting follower self-efficacy.

Organizations can train managers to be transformational and charismatic in their management style. Transformational or charismatic leaders empower their followers through voicing confidence in their ability to do well.

Through articulating a clear vision based on important values, charismatic leaders increase follower self-worth and self-efficacy (Shamir, House & Arthur, 1993). Consequently, interventions aimed at improving leadership behavior can create a positive organizational climate whereby employees have a high sense of self-worth and self-efficacy.

Overall the relationship between self-efficacy and performance is positive although recent research suggests that the effects are due to past achievements rather than to the boost to self-efficacy. It is recommended that managers boost their subordinates’ expectations through showing confidence in their ability.

Critical appraisal of the available evidence: Solidity Level 4

Based on the empirical evidence for the relationship between self-efficacy and individual performance, this dossier is assigned a Level 4 rating, (Based on a 1- 5 measurement scale). A level 4 is the second highest rating for a dossier and the evidence provided on the efficacy of the relationship between self-efficacy and performance.

The research performed demonstrates high validity and reliability due to the replication of the positive effects of self-efficacy on performance. However, the rating of a 4 is due to the lack of relationship between self-efficacy and performance when research is conducted across participants rather than between participants.

Key take-aways

- Self-efficacy refers to one’s belief in ability to carry out a series of behaviors in a specific domain

- Bandura proposed that self-efficacy enhances performance through increasing the difficulty of self-set goals

- Self-efficacy should be measured with a unipolar scale ranging from no confidence to complete confidence

- A considerable body of evidence supports the claim that an increased self-efficacy improves job performance

- Leadership interventions to increase self-efficacy include an effective use of role models, confidence building and expectation management

- Recent research findings suggest that past performance increases self-efficacy rather than self-efficacy increases performance

Management skills newsletter

Join our monthly newsletter to receive management tips, tricks and insights directly into your inbox!

References and further reading

Baden, D. 2012. No more “preaching to the converted”: Embed- ding eased in the business school curriculum through a service-learning initiative. In R. Atfield & P. Kemp (Eds.), Enhancing education for sustainable development in business and management, hospitality, leisure, sport, tourism. York: Higher Education Academy.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 33, 344- 358.

Bandura, A. (2012). On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management, 28, 9–44.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual review of psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1-26). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.

Eden, D. (1988). Pygmalion, goal setting, and expectancy: Compatible ways to raise productivity. Academy of Management Review, 13, 639–652.

Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effect of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4 (4), 577-594.

Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B. and Rogers, R. W. (1982) ‘The Self-Efficacy Scale: Construction and Validation’, Psychological Reports, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 663–671.

Sherer, M., & Adams, C. H. (1983). Construct validation of the Self-Efficacy Scale. Psychological Reports, 53, 899-902.

Sitzmann T, Ely K. (2011). A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educational attainment: What we know and where we need to go. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 421–442.

Sitzmann, T., & Yeo, G. (2013). A meta‐analytic investigation of the within‐person self‐efficacy domain: Is self‐efficacy a product of past performance or a driver of future performance? Personnel Psychology, 66(3), 531-568.

Stajkovic A & Luthans F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A metaanalysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240–261.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2011). Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 121-131.

About the Author