- All Management Learning Resources

- team conflict management

Executive summary

Team conflicts are common occurrences that are difficult to manage. In this CQ Dossier, we ask where team conflicts come from, how they can be managed, and whether they can be beneficial. We take a look at various sources of conflict that shed light on common underlying issues causing team conflicts. Effective, long-term conflict management is holistic and considers the source of conflict, team dynamics, and future outlook. We consider different types of conflict management interventions, and highlight the important role of the team and team cohesion in the process of managing conflict. Finally, we take a look at potential benefits of team conflict and the factors that allow teams to reap these benefits.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Teams are important building blocks of modern organizations

- Team conflicts open avenues for research and understanding

- Why do team conflicts take place?

- The team is not an isolated unit: organizational conflict also influences team conflict

- How to solve team conflicts? Different conflict management strategies

- The ability to manage conflict in teams strongly depends on the team itself

- High performance teams with high cohesion choose holistic strategies organically

- Team cohesion is directly linked to conflict management: cohesion is the basis for long-term benefits

- Can team conflicts be good for teams?

- Conflict can be positive for teams - but not for all

- Teams that overcome conflict further improve team cohesion and effectiveness

- Teams that overcome conflict can be more innovative

- Teams that overcome conflict develop trust

- Conflict can help improve team performance

- It is not good to avoid conflict - regardless of team

- Conclusion

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

Teams are important building blocks of modern organizations

As we have also established in our review of teams, there is widespread consensus that in organizations today, teams are crucial building blocks and methods of choice for organizations to flourish and survive (Tekleab et al, 2009 ; Somech, Desivilya and Lidogoster, 2009). Teams have multiple characteristics, including having complimentary skills, being mutually accountable, and sharing a long-term goal (see Katzenbach and Smith, 1993).

However, teams face conflicts. The term “conflict“ itself often leads to discomfort, although in organizations it simply refers to what happens when team members express differences in values and perspectives (Tuckman, 1965), resulting in struggles and incompatibility. Singh and Antony elaborate that “[team] conflict arises from a multitude of sources that reflect the differences in personality, values, ideologies, religion, culture, race, and behavior” (2006, p2).

Team conflicts open avenues for research and understanding

Conflict itself is not only common, but could even be conceived as a somewhat natural occurence and logical consequence of the inherent differences between people. Some even consider conflict inevitable when groups of people work together (Greer & Dannals, 2017).

A considerable amount of research has been done on conflicts in organizational settings, centring not only on the causes of conflict, but also on types of successful conflict management interventions and on the further impact the conflict might have on other variables, like team dynamics or outcomes (see Somech, Desivilya and Lidogoster, 2009). Conflicts are complex matters. We will consider each of these three aspects - causes, interventions, and consequences - in turn.

Why do team conflicts take place?

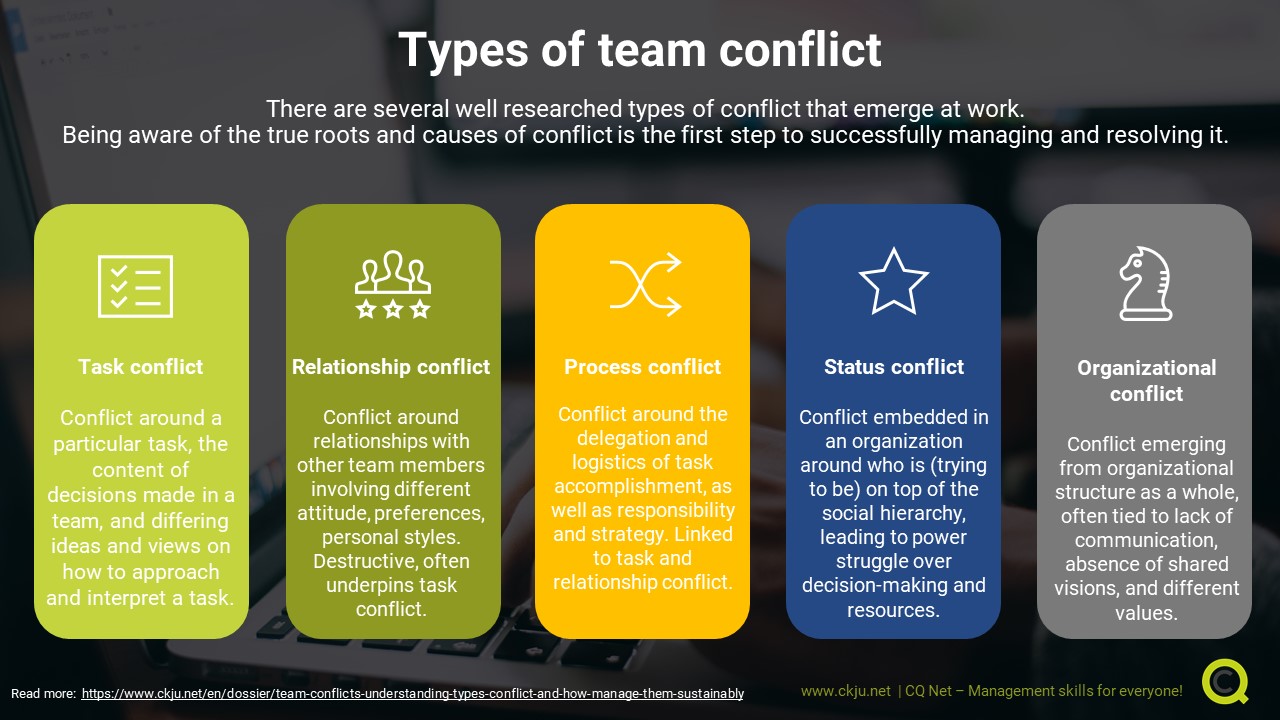

There are varying approaches to studying team conflict and where it comes from: these can be broadly sorted into two categories: intra-group and organizational. On the one hand, research considers the sources of team conflict on the individual and inter-personal level. De Wit, Greer and Jehn (2012) in their comprehensive meta-analysis of intrapersonal conflict identify three main sources of conflict in teams: task conflict, relationship conflict, and process conflict.

Task conflict: conflict because of what

Task conflict, as the name says, revolves around the particular task a team is given. In other words, it is about the content of the decisions made by the team in relation to a specific task (Simons and Peterson, 2000). According to Troth (2009), this type of conflict comes from differences in ideas and views on the task, and sometimes even stems from disagreements on what the task to be done is in the first place. Greer et al. (2012) point out that task conflict is less destructive when it is isolated, i.e. when it is not underpinned by other types of conflict, for example relationship conflict.

Relationship conflict: conflict because of who

In relationship conflict, it is the team members relationships with each other that are at stake. Relationship conflict thus includes differences involving different preferences, personal and interpersonal styles, and attitudes (De Dreu and Weingart, 2003). This is one of the types of conflict most likely to be destructive to teams, because it is often linked to negative emotions, hostility and personal dislike, which is not only destructive but also distracting (Greer et al., 2012). For some scholars (Simons & Peterson, 2000), relationship conflict is a shadow of task conflict, as the quality of inter-group relationships is linked to the ability to solve tasks together.

Process conflict: conflict because of how

Process conflict has to do with the delegation of tasks and the process through which team tasks are solved, that is to say, the logistics of accomplishing a task. Conflict arises when there are disagreements over task division and responsibility, as well as strategy on how to best tackle the task (Behfar, Peterson, Mannix and Trochim, 2008). Process conflict is considered by De Wit, Greer and Jehn (2012) as the worst form of intra-group conflict: not only is it linked to a specific task, but the issues at hand is often linked to disagreements about who is in which role and gets to control resources, meaning it shows attributes of relationship conflict too.

The team is not an isolated unit: organizational conflict also influences team conflict

On the other hand, going beyond intra-group conflict, there is also team conflict that is embedded into broader organizational dynamics. This type of conflict assumes that a team and an organization mutually influence each other, therefore intra-personal relations cannot be seen in isolation (see George and Jones, 1997).

Status conflict: conflict because of who is where

There is evidence that the social hierarchy within a group can be a source of conflict. Bendersky and Hays (2012) in their literature review show that it is natural for teams to form into social hierarchies, leading to power struggles over social esteem and control over decisions or resources. This form of conflict is structural, meaning there is usually no interest in conflict outcomes, but rather in the broader achievement of a social position or function, which may well exceed beyond the team (see Benjamin and Poldony, 1999).

Organizational conflict: conflict because of structure

This context-related source of conflict refers to the actual make-up of an organization and the rules, norms and values it represents. For example, organizations with limited knowledge, various cultural values and traditions, and different work ethics and visions are less likely to engage in negotiation processes but rather act unilaterally and forcefully (see Morrill, 1995). Their organizational counterparts with similar working styles, values and goals are more likely to communicate, negotiate, and seek compromise and conflict resolution. In organizations that are less attuned, there is a likelihood that status struggles will emerge, as power positions bring great benefits to those who attain them (see Ridgeway and Correll, 2006).

Management skills newsletter

Join our monthly newsletter to receive management tips, tricks and insights directly into your inbox!

How to solve team conflicts? Different conflict management strategies

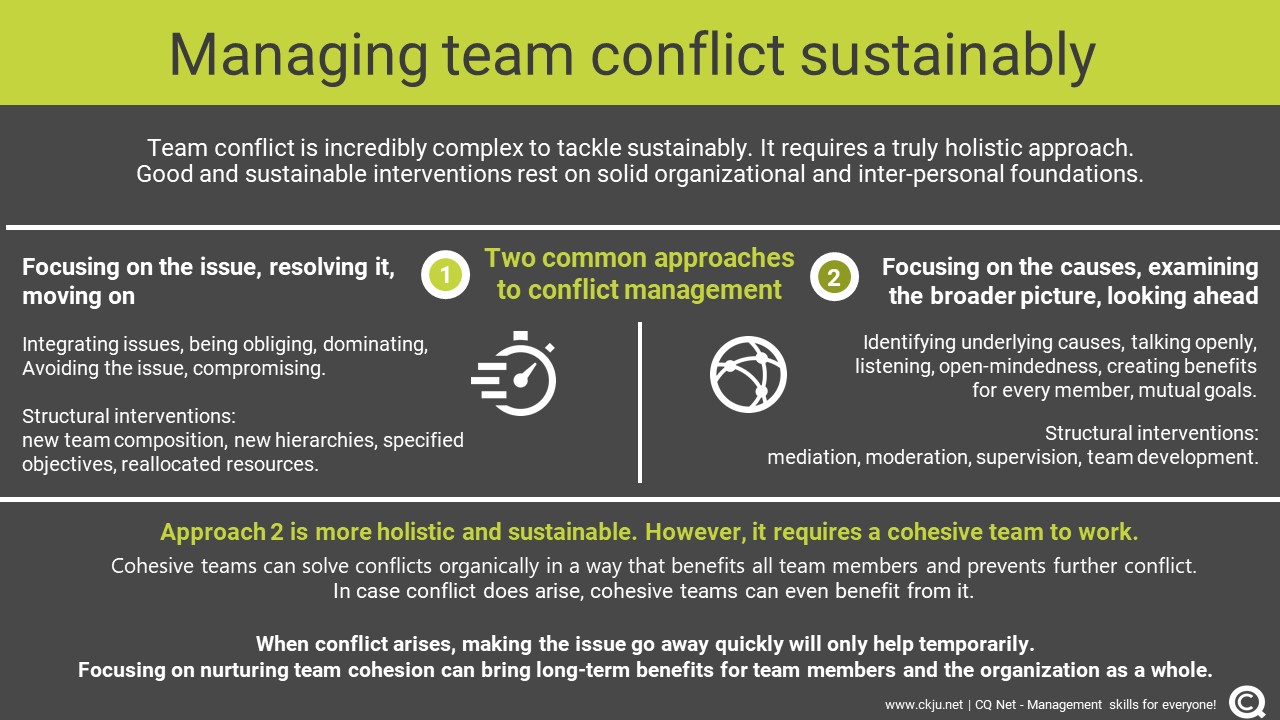

Generally, the rule of thumb in organizational studies is that what matters in conflict management is not the conflict itself, i.e. the concrete issue, but the way in which it is managed (Rayeski & Bryant, 1994). The first step to determining how to best manage conflict is to understand the causes of the issue. The second step is to evaluate the objective: is the goal to simply end the conflict, or to lay the foundations that prevent it from happening again in the future?

Arguably, these are the two broad directions that conflict management interventions could take:

Focus on the conflict, issues underpinning it, and resolving the situation

This form of conflict management could be considered the “traditional” type, referring to management interventions that make conflicts vanish quickly. However, there is a high chance that conflicts re-appear.

Research originally carried out by Blake and Moutin (1964), which was extended and modified several times, points to five intra-personal strategies usually found in this sphere:

- integrating,

- obliging,

- dominating,

- avoiding, and

- compromising.

In addition, Proksch (2016) lists “top-down” interventions like new team composition, redefining hierarchies, specifying objectives and reallocating resources as measures that are readily employed but don’t have long-term benefits. Rather, these strategies are likely to make the conflict re-emerge at some point.

Focus on the causes of the problem, the broader picture, and future outcomes

On an inter-personal level, cooperative approaches that prioritise collective goal-attainment are beneficial. Building on Deutsch’s theory of collaboration and competition (1973), inter-group strategies that help solve conflict sustainable include:

- identifying underlying causes together

- emphasizing cooperative goals

- communicating openly

- listening open-mindedly

- practicing empathy and understanding

- promote mutual goals and resolve problems for mutual benefit

Such strategies help team members be productive, bolster confidence and trust, and help nurture the belief that future problems can also be solved together (see Tjosvold, 1998).

In the same context, Proksch (2016) lists basic forms of “top down” conflict management. These look beyond the traditional, “mechanistic” methods described in the previous category and also echo the nature of inter-personal strategies :

- mediation

- moderation

- supervision

- coaching

- team development

These management interventions take into account the “life” of the organization and seek to focus on individuals, their needs, and integrative measures to improve the situation for the team on the long run. Proksch also points to broader organizational development as a so-called “complementary method”, which could be characterized for example by structures that foster collaborative relationships (Almost et al., 2016).

The ability to manage conflict in teams strongly depends on the team itself

Conflict is unbelievably complex and affected by multiple factors that influence the conflict itself, the style or methods with which it is to be best managed, and the outcomes that emerge (see Almost et al., 2016). However, the most important actor in managing team conflict is - not surprisingly - the team.

Regardless of whether it is an external management intervention or a conflict management strategy employed within the team, the team itself is the player who is determinant of whether the team conflict will be resolved, and how. Without the team and its willingness to address the conflict and act on it, team conflicts cannot be managed with long-lasting results (see Tekleab et al., 2009).

High performance teams with high cohesion choose holistic strategies organically

There is research that shows that high-performing teams with a strong emphasis on team cohesion tend to naturally employ distinct conflict management strategies compared to other teams.

In a study conducted in 57 autonomous teams by Behfar, Peterson, Mannix and Trochim (2008), a model was developed that highlights four clusters of conflict management strategies employed by teams themselves along a matrix: on the vertical axis, conflict resolution strategies were split into pluralistic (i.e. tackling the whole team and applying to everyone equally) versus particularistic (i.e. focusing on individual solutions and situations). On the horizontal axis, they were split into reactive (i.e. looking back on a situation and reacting to it), versus pre-emptive (i.e. taking resources to invest into solutions before issues arise).

High performing, cohesive teams were likely to use pre-emptive and pluralistic strategies, like the ones outlined in the section on interventions focusing on long-term outcomes.

Contrastingly, teams with low levels of performance were likely to use reactive and particularistic strategies. As such, there is a distinct correlation between performance, team cohesion, and conflict management strategies - teams with high performance and outcomes are more likely to manage conflict in a sustainable and goal-oriented way that prevents future conflict from arising.

In the context of this Dossier, this shows that once team cohesion and high performance has been attained by a team, the team is likely to organically choose a conflict management intervention that includes all team members and lays the groundwork for the prevention of further conflict. This indicates that team cohesion is linked to inter-personal, holistic conflict management strategies.

Team cohesion is directly linked to conflict management: cohesion is the basis for long-term benefits

Indeed, teams who can directly and openly address conflicts should be better able to develop a long-term, open, healthy, and constructive atmosphere (see Tekleab et al., 2009) that allows them to practice holistic team conflict intervention strategies. Teams who are successfully able to use holistic strategies are likely teams with high levels of team cohesion, which is not only beneficial for conflict management, but also has positive effects on performance.

Cohesive teams also exhibit establish shared identities, shared contexts and shared visions, which has been shown to help mitigate conflict (Hinds & Mortensen, 2005). As such, it is fair to state that team cohesion is a fundamental requirement of effective conflict management.

On the other hand, teams that exhibit low levels of cohesion, unaddressed and severe issues, general fragmentation, bad communication, a psychologically unsafe climate or lacking trust, can lead to very difficult situations. Here, it may make sense to look beyond the conflict and to take an approach that starts at the root of the problem: the team itself.

Can team conflicts be good for teams?

The short answer is - yes, they could be. However, it is not the conflicts per se, but rather the way they are managed that can lead to good team and organizational outcomes.

Indeed, there is scientific evidence that conflict could be truly beneficial for teams - that is, if the conflict does not exceed a certain threshold of intensity (see Deutsch, 1973), is managed well, and rests on foundations of high levels of team cohesion (see Hinds and Mortensen, 2001).

Team conflicts can also give rise to critical evaluation and reflection, which starts at the very root causes of conflict. Dealing with these underlying causes can help determine which aspects influence the conflict and need to be worked on. However, the type of team and the willingness to solve the conflict matters.

Conflict can be positive for teams - but not for all

It is important not to forget that these relationships are almost never unidirectional - there is no guaranteed causal relationship between conflict and positive outcomes. A conflict can be useful for some teams, but detrimental to others. Nonetheless, there are promising trends that highlight possible long-term, positive effects of effective conflict management, which are all interrelated:

Teams that overcome conflict further improve team cohesion and effectiveness

There is evidence that team cohesion mediates the relationship between conflict and team effectiveness. This is particularly true for task conflict (see Peterson, 1997). Cohesive teams who actively address and discuss (task) conflicts are able to better understand each other in the long run (Edmondson and Smith, 2006). However, the evidence is not clear as there are factors like relationship conflict and group dynamics that further influence this complex relationship (Tekleab et al., 2009).

Teams that overcome conflict can be more innovative

A study by Lovelace et al. (2001) found that overcoming task conflict, so disagreement about particular tasks, can be beneficial for team innovation as it helps team members speak openly about their concerns and discuss new ways to deal with the conflict at hand. This, in turn, helps nurture a positive climate of creativity, communication, and trust, which feeds into innovation (Hinds and Mortensen, 2001).

Teams that overcome conflict develop trust

Trust is a tool for conflict management, but is also a consequence thereof. Omisore and Abiodun (2014) find that overcoming conflict as a team can help improve personal initiative, innovation, communication, mutual understanding, and opinions. As such, the trust that grows within teams helps mediate between task and relationship conflict. That means that conflicts related to tasks are less likely to be fueled by interpersonal reasons conflict. Trust is beneficial particularly for mediating between task and relationship conflict (Simons and Peterson, 2000).

Conflict can help improve team performance

A review by de Dreu and Weingart (2003) shows that most studies actually show a negative relationship between managing conflict and improved performance. Recent research however shows that particularly for task performance, overcoming it together can help interpersonal relations, which helps group performance and cooperation (Alper, Tjosvold & Law, 2000). Bradley et al. (2012) find that performance is only improved if conflict management takes place within a psychologically safe environment.

It is not good to avoid conflict - regardless of team

Research has shown that avoidance behaviors in team conflict (both avoiding the conflict from arising and avoiding dealing with the conflict) have negative effects on teams as a whole. Not only could avoidance aggravate existing differences, but it also reduces the team’s overall potential as the possibilities hidden in conflict management and the evaluation of causes and opportunities are not tapped into (Tjosvold, Law & Sun, 2006; Tjosvold, 2008).

This points to the positive effects of conflict: addressing conflict helps deal with underlying issues. Managing these issues can help teams work better together in the long run. Of course, realistically speaking, teams often do avoid conflicts and not all teams can address issues. This can lead to escalations.

In such situations, it makes sense to look at context and to consider broader interventions to (re)build team cohesion, develop new teams as a whole, or even resort to large-scale approaches relating to organizational development. In either scenario, a conflict can be a great agent for change management.

Conclusion

Teams are complex entities that experience conflicts. Team conflict can have many causes which are important to understand, as these can determine which intervention makes sense. Whether it be top-down or coming from the team, resolving a conflict is an important act. The team itself is the most vital player in finding solutions for team conflict. As such, factors like team cohesion play an important role in determining which interventions can be successful in the first place. Teams with high levels of cohesion can even benefit from team conflict when it arises. Therefore, conflict can be an opportunity for growth and not an occurrence that should be avoided, stifled, or ignored. Team conflicts are extremely complex and multi-faceted, but holistic interventions starting at the very foundations of the team and of conflict can turn them into opportunities.

Key take-aways

- Team conflict is complex and there is no one-size-fits-all formula that solves conflicts

- Different sources of conflict include task, relationship, process, status, and organizational conflict

- Conflict resolution strategies either focus on solving the issue or on preventing it from happening again in the future

- Whether or not conflict can be successfully managed at all strongly depends on the team

- High performance, high cohesion teams organically turn to participatory and pre-emptive measures

- Cohesive teams are more likely to benefit from conflict and conflict management

References and further reading

Almost, J., Wolff, A. C., Stewart-Pyne, A., McCormick, L. G., Strachan, D., & D'Souza, C. (2016). Managing and mitigating conflict in healthcare teams: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(7), 1490–1505.

Alper, S., Tjosvold, D., & Law, K. S. (2000). Conflict management, efficacy, and performance in organizational teams. Personnel Psychology, 53(3), 625–642.

Behfar, K. J., Peterson, R. S. [Randall S.], Mannix, E. A., & Trochim, W. M. K. (2008). The critical role of conflict resolution in teams: A close look at the links between conflict type, conflict management strategies, and team outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 170–188.

Bendersky, C., & Hays, N. A. (2012). Status Conflict in Groups. Organization Science, 23(2), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0734

Benjamin, B. A. and Poldony, J. M. (1999). Status, quality and social order in the California wine industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(3), 563–589.

Blake, R., & Mouton, J. (1964). The managerial grid. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Bradley, B. H., Postlethwaite, B. E., Klotz, A. C., Hamdani, M. R., & Brown, K. G. (2012). Reaping the benefits of task conflict in teams: The critical role of team psychological safety climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 151–158.

de Wit F. R. C., Greer L.L. and Jehn, K.A. (2012). The paradox of intragroup conflict: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97,360–90.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict: Constructive and destructive processes. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dreu, C. K. W. de, & Weingart, L. R. (2003). Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.4.741

Edmondson, A. C., and D. M. Smith. (2006). Too Hot to Handle? How to Manage Relationship Conflict. California Management Review, 49(1), 6–31.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1997). Experiencing work: Values, attitudes, and moods. Human Relations, 50(4), 393–416.

Greer, L. L., & Dannals, J. E. (2017). Conflict in teams. In R. Rico, E. Salas, & N. Ashkanasy, The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Team Dynamics, Teamwork, and Collaborative Working. Somerset, NY: Wiley Blackwell.

Greer, L. L., Saygi, O., Aaldering, H., & de Dreu, C. K. W. (2012). Conflict in medical teams: opportunity or danger?. Medical Evaluation, 46(10), 935-942.

Katzenbach, Jon R, and Douglas K. Smith (1993). The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press.

Lovelace, K., Shapiro, D. L., & Weingart, L. R. (2001). Maximizing cross-functional new product teams’ innovativeness and constraint ad-herence: A conflict communications perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 779–783.

Morrill, C. (1995). The executive way: conflict management in corporations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mortensen, M. and Hinds, P. (2001). Conflict and shared identity in geographically distributed teams. International Journal of Conflict Management, 12(3), 212-238.

Omisore, B.O., & Abiodun, A.R. (2014). Organizational Conflicts: Causes, Effects and Remedies. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences, 3(6).

Peterson, R. S. (1997). A directive leadership style in group decision making can be both virtue and vice: Evidence from elite and experimental groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1107— 1121.

Proksch, S. (2016). Conflict management. Switzerland: Springer.

Rayeski, E., & Bryant, J. D. (1994). Team resolution process: A guideline for teams to manage conflict, performance, and discipline. In M. Beyerlein & M. Bullock (Eds.), The International Conference on Work Teams Proceedings: Anniversary Collection. The Best of 1990 - 1994 (pp. 215-221). Denton: University of North Texas, Center for the Study of Work Teams.

Ridgeway, C.L. & Correll, S.J. (2006). Consensus and the Creation of Status Beliefs. Social Forces, 85 (1), 431-453

Simons, T. L., & Peterson, R. S. [R. S.] (2000). Task conflict and relationship conflict in top management teams: The pivotal role of intragroup trust. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 102–111.

Singh, A.K. & Antony, D. (2006). Conflict management in teams: causes & cures. Delhi Business Review, 7(2), 1-1.

Somech, A., Desivilya, H.S. and Lidogoster, H. (2009). Team conflict management and team effectiveness: the effects of task interdependence and team identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 359-378.

Tekleab, A. G., Quigley, N. R., & Tesluk, P. E. (2009). A Longitudinal Study of Team Conflict, Conflict Management, Cohesion, and Team Effectiveness. Group & Organization Management, 34(2), 170–205.

Tjosvold, D. (1998). Cooperative and competitive goal approach to conflict: Accomplishments and challenges. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 47(3), 285–342.

Tjosvold, D. (2008). The conflict-positive organization: It depends on us. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29: 19–28.

Tjosvold, D., Law, K. S. and Sun, H. (2006). Effectiveness of Chinese teams: The role of conflict types and conflict management approaches. Management and Organization Review, 2: 231–252.

Troth, A.C. (2009). A model of team emotional intelligence, conflict, task complexity and decision making. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, 14(1), 26-40.

Tuckman, Bruce W. (1965) ‘Developmental sequence in small groups’, Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399. The article was reprinted in Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal, Number 3, Spring 2001.

About the Author