- All Management Learning Resources

- Workplace safety

Executive summary

This CQ Dossier focuses on what constitutes an effective safety climate and how to improve workplace safety in general. Recent disasters such as the Grenfell Tower Fire incident illustrate the importance of safety in the work environment. At the Grenfell Tower, people escaped using a single staircase and while more than 65 people were rescued, an estimated 71 people died and countless others were injured (Castle et al. 2017). A recent report on the Grenfell Tower incident found that there were organizational problems within the building industry that led to the fire (Hackitt, 2018). One of the main problems was the lack of an effective safety climate. In this CQ Dossier we describes the key elements of an effective safety climate and focuses on organizational and individual factors that are antecedents of effective workplace safety.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Workplace safety basics: Safety climate is more transcient than safety culture

- Five factors determine workplace safety climate

- Safety climate is a multi-level concept covering organizational and group level

- Leadership in combination with safety policies, procedures, rewards drives workplace safety

- BP Deep Water Horizon Accident: The role of top management in workplace safety

- CEOs have to drive workplace safety in their management teams

- There is more about workplace safety than safety climate: Four factors of workplace safety and how to improve them

- Personality, attitudes, and belief predict safe working behavior

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

Workplace safety basics: Safety climate is more transcient than safety culture

First, it is important to differentiate between safety climate and safety culture:

- Safety culture is the product of individual group values and patterns of behavior that reflect an organization’s health and safety management. These values are deep and rooted in tradition and the history of the organization.

- Safety climate is more transient and is reflective of individual states or moods. It is the shared perceptions among organizational members of safety policies, procedures and practices (Wallace, Popp & Mondore, 2006).

Employees do not directly respond to the work environment but first reflect and interpret on environmental stimuli; then they act according to their diagnosis of the environment (Wallace et al., 2006).

The first formal definition of safety climate was developed by Dov Zohar (1980). Zohar defined safety climate as “a summary of molar perceptions that employees share about their work environment” (Zohar 1980). The model was tested among Israeli workers across a variety of industries. This seminal study established a method to assess safety climate through assessing shared perceptions of an organization’s safety climate.

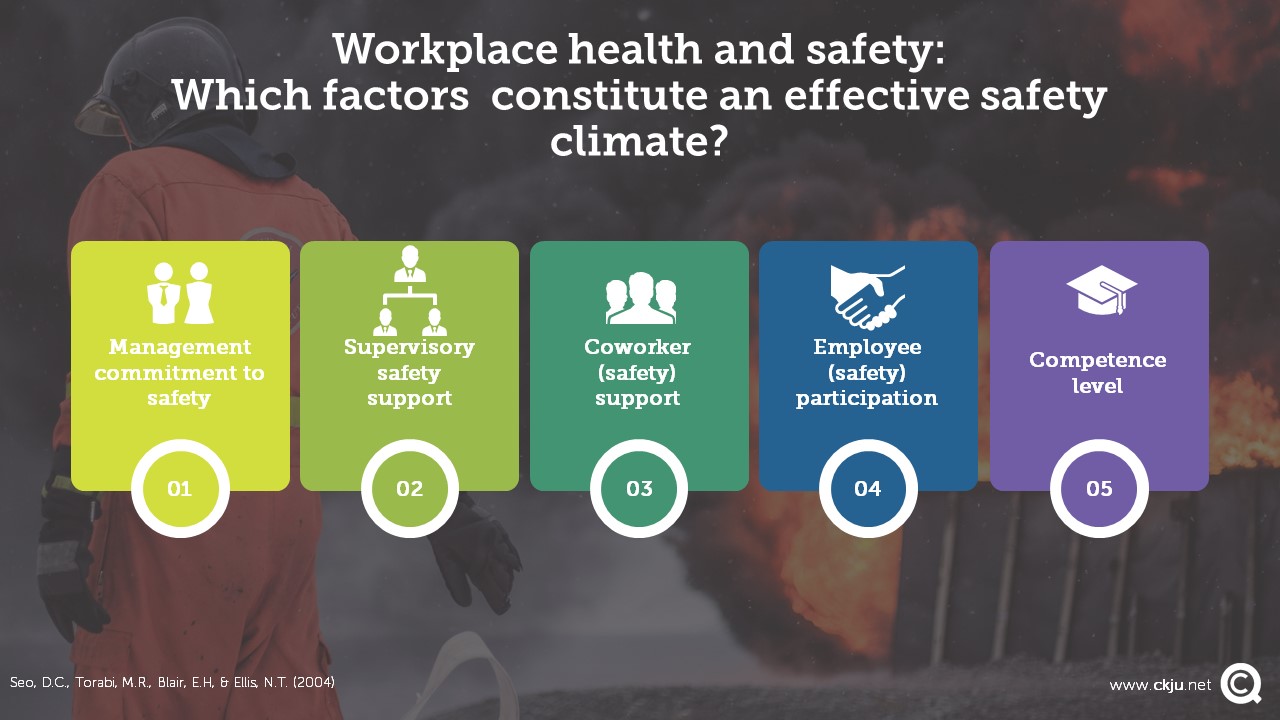

Five factors determine workplace safety climate

An organization’s climate and safety culture will impact the safety performance of individuals. Research has shown that work health and safety practices are important in fostering a safety climate (Zohar et al., 2014). The concept of safety climate is a good predictor of safety behavior (Beus et al., 2016). Zohar’s (1980) original safety climate factors included the following:

- Importance of safety training,

- Effects of required work pace on safety,

- Status of safety committee,

- Status of safety officer,

- Effects of safe conduct on promotion,

- Level of risk at work place,

- Management attitudes toward safety and

- effect of safe conduct on social status.

A recent review of the literature concluded that the set of critical factors has not really diverged from this original 1980s set of dimensions. Seo and colleagues (2004) found that the themes clustered into five core constructs of safety climate:

- Management commitment to safety,

- Supervisory safety support,

- Coworker (safety) support,

- Employee (safety) participation and,

- Competence level.

Safety climate is a multi-level concept covering organizational and group level

More recently, Zohar (2000) has also acknowledged the multi-level nature of safety climate and argued that group members must have shared cognitions regarding safety priorities and expectations (Zohar, 2010). This logic resulted in a new multi-level model and safety climate questionnaire (Zohar & Luria, 2005). Two levels emerged from the study – organizational safety climate and group safety climate constructs.

The study revealed that safety climate is complex and multi-level; company policies predicted organizational climate perceptions and these predicated how supervisors behave in accordance with these policies. Supervisory practices of safety were related to group-level climate perceptions, showing that employees determine the importance of safety based on the actions of their supervisor. If supervisors make safety requirements contingent on production deadlines, workers will infer low safety priority even if it is stated by top management that safety has top priority (Zohar & Luria, 2005).

Leadership in combination with safety policies, procedures, rewards drives workplace safety

Griffin and Neal (2000) also acknowledge the multi-level nature of safety climate. Based on their research, they conceptualize safety climate as a high order factor comprised of specific first order factors including safety policies, procedures and rewards. The higher order factor is the extent to which employees believe that safety is valued within the organization. This higher-order factor is important because research shows that employees look to management to determine what constitutes safe behavior. If management espouse safety as important but then focus on profitability, employees will perceive the organization to place little value on safety. This especially applies to organizations and top management teams that strongly focus on goals and their achievment in form of key performance indicators (KPIs). When they put too much focus on goals, there is a risk of negative side effects that can also undermine workplace safety.

BP Deep Water Horizon Accident: The role of top management in workplace safety

Because organizational safety climate predicts group-level safety climate, there is evidence to suggest that leaders can drive an effective safety climate. Management commitment to safety is important because team members look to their leaders to determine whether safety is important (Zohar & Luria, 2005). A recent study found that top management is instrumental in driving safety behaviors. Tucker and colleagues (2016) found that chief executive officers indirectly impact workplace injuries. One of the reasons for conducting the study was following an investigation into the BP Deep Water Horizon Explosion, which took the lives of 11 workers (Tucker et al., 2016).

CEOs have to drive workplace safety in their management teams

There was much criticism of the BP CEO and the top management team (TMT) and the researchers wished to analyze the extent to which leaders impact accidents. They found that when the CEO drove a TMT safety climate, this was positively related to organizational supervisors’ reports of the broader organizational safety climate. In turn, this supervisor support for safety was associated with fewer employee injuries. This research show that an effective safety climate involves many parties and is not just the responsibility of the individual.

There is more about workplace safety than safety climate: Four factors of workplace safety and how to improve them

Older theories of what leads to fewer accidents in the workplace focused on human error viewing human error as a predictor rather than a symptom of deep flaws in the system (Wallace, Popp & Mondore, 2006). New models now show that the picture is more complex and that occupational safety needs to address the following four factors (Wallace et al., 2006):

- work design

- safety climate

- individual differences

- affective, motivational and cognitive processes.

When there are disasters and accident in the workplace, such as the Grenfell Tower disaster or the Challenger Spacecraft accident, many professionals focus on identification of technical issues to examine why these accidents happen. However, this focus on technical issues ignores the individual and organizational factors that contribute to safety. It is critical to consider the probability of loss to human life and to consider those factors that decrease the likelihood of an accident occurring. Individual and organizational factors are multi-level and interdependent with safety behavior occurring at the individual contributing to safety behavior at the organizational level (Zohar et al., 2014). In addition, organizational culture can contribute to the safety at the individual level (Zohar et al., 2014).

Implement an effective organizational policy on safety

The best safety climate policies are those that focus on safety compliance and safety participation (Christian et al., 2009; Neal & Griffin, 2004). Safety compliance behaviors are vital in maintaining workplace safety and include behaviors such as using appropriate protective equipment and following standardized operating procedures also referred to as SOPs (Christian et al., 2009).

Foster safety participation to improve workplace safety

Safety participation is important in developing a workplace environment that supports safety (Christian et al., 2009). Safety participation behavior include (Griffin & Neal, 2000):

- volunteering to be on safety committees,

- participating in safety campaigns, and

- promoting safe working practices, especially amongst co-workers.

Gain management commitment to safety

It is important to gain management commitment to safety because employees are influenced by management behavior regarding safety. In fact, research has shown that leaders play an important role in cultivating an effective safety climate (Neal & Griffin, 2004). When management make statements and engage in actions regarding the importance of safety, this fosters a belief in employees that there is an effective safety climate. Moreover, it is important that management regularly respond to issues regarding safety to show that their actions are consistent with their statements.

Supervisors who engage in a high level of safety leadership can directly influence risk perception by influencing employees’ comprehension of safety issues, their motivation to follow safety procedures, and actual safety compliance. These types of safety leadership behaviors include

- frequent visits to working sites to ensure that safety protocols are being followed,

- praise and recognition for safety behaviors; constructive feedback for risk behaviors,

- and various communication activities to convey statement related to safety.

These types of behavior can lower employees’ perception of risk (Nielsen & Cleal, 2011).

Implement workplace safety training initiatives

One of the key factors that contributes to an effective safety climate is that organizations design, implement, and evaluate safety training initiatives. The safety training must be relevant to the individual’s role so that employees are committed to learn the knowledge and skills relevant to the safety components of their job (Clarke, 2010).

In addition, supervisors can also engage in simple on-the-job safety education and training, to lower employees’ perception of risk; these kinds of behaviors also increase the perception that the organization has an effective safety climate. Research within the construction industry, which has a high level of accidents, showed that safety training can make a difference in reducing accidents. Cooper and Phillips (2004) found that safety training promotes employee safety behaviors. Safety training is related to employees’ safety perceptions and these perceptions are directly related to safety climate.

One example of an industry that requires employees to get regular trainings on individual and team factors to prevent accidents is the aviation industry. The training is called "Crew Resource Management" or CRM and puts an emphasis on non-technical skills (NOTECH) individuals and teams require to perform in complex and dynamic environments.

Promote workplace safety behaviors within the organization

It is important that organizations actively promote safety behaviors in order to increase perceptions of safety climate. The most effective organizations are those that balance safety with competing factors such as productivity and work pace (Neal & Griffin, 2004). Promotion of safety behaviors must originate from senior executives who play an instrumental role in fostering safety throughout the organization (Neal & Griffin, 2004).

Personality, attitudes, and belief predict safe working behavior

Research on safety climate has also identified the influence of individual factors such as personality, attitudes, and belief in predicting safe working behavior (e.g., Hogan & Foster, 2013). Research on personality has focused on the Big Five Personality Model and has identified conscientiousness and neuroticism as two significant predictors of safety behavior (e.g., Hogan & Foster, 2013); Wallace & Chen, 2006). Employees who score high on conscientiousness tend to be methodical, organized and more likely to follow procedural processes so are more safety-focused (Hogan & Foster, 2013); Wallace & Chen, 2006) whereas employees who are neurotic tend to be more careless, less reliable and less likely to comply with procedures (Neal & Griffin, 2004).

Conscientiousness predicts safe behavior

A recent review of the literature by Hoffman and colleagues describes the consistency of relationships between personality and safety-related behavior with conscientiousness emerging as a predictor of safe behavior (Hoffman, Burke & Zohar, 2017).

Sensation seeking is related to unsafe behavior

In addition, sensation seeking is more strongly related to unsafe behavior (Hoffman et al., 2017). The connection between personality and safety-related behavior can be addressed during employee selection practices.

In conclusion, organizational factors and individual differences contribute to formation of an effective safety climate. It is important to consider these factors because it allows organizations to formulate policy and practices concerning safety. Safety climate is important because it predicts accident and safety behaviors at work. Consequently, it is important to consider the antecedents of safety climate.

Key take-aways

- Safety culture is long-term and deep-routed

- Safety climate denotes shared perceptions and is transient

- Management attitude towards safety is important

- Management must emphasize safety training

- Establish key positions and groups such as a safety committee and officer

- Leaders drive an effective safety climate

- Occupational safety involves multiple factors and is not just human error

- Safety training must be relevant to the individual’s role

- Balance safety with productivity and work pace

- Personality traits are predictors of safety behavior

Management skills newsletter

Join our monthly newsletter to receive management tips, tricks and insights directly into your inbox!

References and further reading

Beus, J.M., McCord, M.A., & Zohar D. (2016). Workplace safety: a review and research synthesis. Organizational Psychological Review, 6, 4, 352–381.

Castle, S; Hakim, D; & Yeginsu, C (2017) Questions mount after fire at Grenfell Tower in London kills at least 12 The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/13/world/europe/fire-london-apartment-building.html Accessed on 15 Oct 2017.

Christian, M. S., Bradley, J.C., Wallace, J.C., & Burke, M.J. (2009). Workplace safety: a meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1103-1127.

Cooper, M.D,, & Phillips, R.A. (2004). Exploratory analysis of the safety climate and safety behavior relationship. Journal of Safety Research, 35, 5, 497-512.

Griffin, M. A. & Neal, A. 2000. Perceptions of safety at work: a framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 3, 347-358.

Hackitt, J. (2018). Building a safer future. Final Report. Independent Review of Building regulations and Fire Safety.

Hoffman, D., Burke, M., & Zohar, D. (2017). 100 Years of Occupational Safety Research: From Basic Protections and Work Analysis to a Multilevel View of Workplace Safety and Risk. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102, 3, 375-388.

Hogan, J., & Foster, J. (2013). Multifaceted personality predictors of workplace safety performance: more than conscientiousness. Human Performance, 26, 1, 20–43.

Neal A., & Griffin M.A. (2004). Safety climate and safety at work. In: Frone M.R., Barling J., (editors). The Psychology of Workplace Safety. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC.

Nielsen, K., & Cleal, B. (2011). Under which conditions do middle managers exhibit transformational leadership behaviors? An experience sampling method study on the predictors of transformational leadership behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 2, 344-352.

Seo, D.C., Torabi, M.R., Blair, E.H, & Ellis, N.T. (2004). A cross‐validation of safety climate scale using confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Safety Research 35(4): 427‐445.

Tucker, S., Ogunfowora, B., & Ehr, D. (2016). Safety in the c-suite: How chief executive officers influence organizational safety climate and employee injuries. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(9), 1228-1239.

Wallace, J. C., Popp, E., & Mondore, S. (2006). Safety climate as a mediator between foundation climates and occupational accidents: A group-level investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 681-688.

Zohar D. 1980. Safety climate in industrial organizations: theoretical and applied implications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65: 96‐102.

Zohar, D., & Luria, G. (2005). A multilevel model of safety climate: Cross-level relationships between organization and group-level climates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 616–628.

Zohar D., Huang Y.H., Lee J., & Robertson M.M (2014). A mediation model linking dispatcher leadership and work ownership with safety climate as predictors of truck driver safety performance. Accident Analysis Prevention, 62:17–25.

About the Author