- All Management Learning Resources

- Culture impacts communication

Executive summary

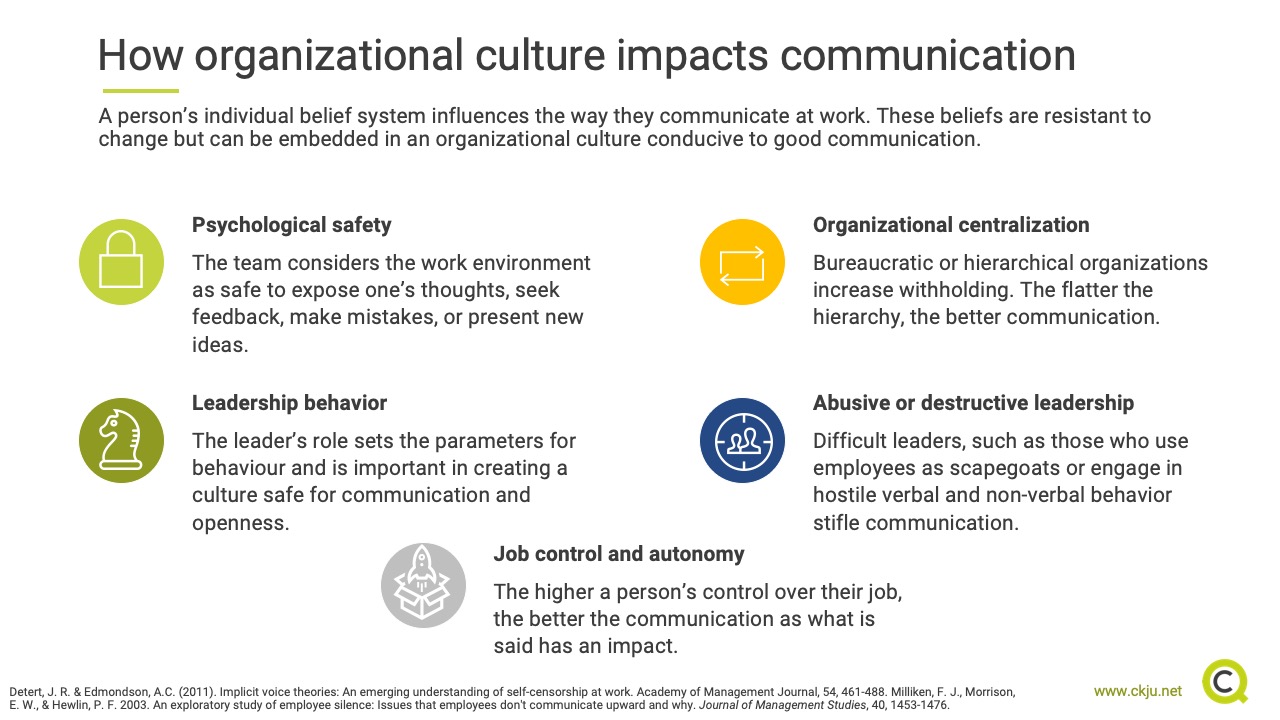

This CQ Dossier describes how organizational culture impacts communication in the workplace alongside the internal belief systems of employees. Research has found that psychologically safe cultures with flat organizational hierarchies encourage communication, but a person’s internal belief system (irrespective of culture) also affects their willingness to communicate at work.

Contents

- Executive summary

- What is organizational culture and how does it impact the workplace?

- Both organizational culture and internal beliefs impact workplace communication

- Numerous cultural variables affect communication.

- The impact of organizational culture on workplace communication is not entirely conclusive

- Internal beliefs help us to quickly form opinions and act on them

- Internal beliefs are stable and tend to be resistant to external influences

- Effective communication at work can be nurtured through an organizational culture that takes into account internal beliefs of employees

- Key take-aways

- Refences and further readings

What is organizational culture and how does it impact the workplace?

Around the world, there are tens of thousands of organizations, and each one has its own unique culture. Culture has many definitions, but it is easy to think of it as a set of norms, values, and principles shared among people in an organization (Needle, 2004). These values and principles tell us everything from what to wear to whether or not we should eat at our desks.

Additionally, an organization’s culture also tells us a lot about how we should communicate with our coworkers. Should we talk openly to people at all levels? Should we be careful about speaking upward? Do people want certain kinds of information in emails or do they want it discussed at meetings? The answers to these questions can be a part of an organization’s culture, which dictates norms for communication.

Both organizational culture and internal beliefs impact workplace communication

In recent years, researchers have found that culture doesn’t act alone when influencing communication in the workplace. In addition to culture, internal belief systems about communication also affect what people choose to say and what they choose to withhold. These internal beliefs are actually formed outside of the workplace, but people bring these belief systems to work and they govern behavior (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). Therefore, without examining internal beliefs, looking at culture alone would provide an incomplete explanation of what underlies the decision to communicate or withhold in the workplace.

Milliken, Morrison, and Hewlin (2003) proposed that part of the acclimation process to a workplace includes learning what is okay to discuss and what one should be quiet about. Essentially, they argued that people should learn the organization’s culture and adjust their communication style to match it. There are numerous cultural variables that affect communication, so only the most significant ones will be discussed in this CQ Dossier.

Management skills newsletter

Join our monthly newsletter to receive management tips, tricks and insights directly into your inbox!

Numerous cultural variables affect communication.

Psychological safety

One of the strongest variables that affects communication is psychological safety. Psychological safety is the “shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking” (Edmondson, 1999 p. 5). A psychologically safe environment is one where people expect others to respond positively when one exposes one’s thoughts, such as by asking a question, seeking feedback, reporting a mistake, or proposing a new idea.

Therefore, employees who feel that their environment is psychologically safe are less likely to withhold communication since the team is not perceived as likely to embarrass or reject them. Team psychological safety can be measured using Edmondson’s (1999) 7-item scale, which includes items such as, “Members of my unit are able to bring up problems and tough issues” and “it is safe to take a risk in my unit” in which people rate these items on a scale ranging from (1) highly inaccurate to (7) highly accurate.

Organizational (de)centralization

Milliken et al. (2003) suggested that employees’ perception of their organization’s centralization is likely to influence voice. Organizations that are high in centralization feel bureaucratic and hierarchical, and they increase withholding by employees.

The degree to which an organization is centralized in this manner can be empirically measured by a scale developed by Hage and Aiken (1969). A representative item from this scale is “Even small matters have to be referred to someone higher up for an answer” with a 4 point scale ranging from (1) definitely false to (4) definitely true.

Leadership behavior

The behavior of leaders in an organization sets the culture and affects communication. Culture is often said to come from the top, and leaders certainly have an important role to play in the creation of a culture that is safe for communication. For example, leader openness is positively related to voice (Detert & Burris, 2007; Dutton, Ashford, Lawrence, & Miner-Rubino, 2002).

Leader openness can be measured on a scale that includes items such as, “My boss is interested in my ideas” with rating choices from (1) never to (7) always.

Abusive or destructive leadership

Furthermore, leaders who are difficult to work with tend to stifle communication. The variable called abusive supervision, defined as “subordinate's perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000, p.178) has a significant negative relationship to communication (Burris, Detert, & Chiaburu, 2008).

Abusive supervision is closely related to destructive leadership and can be measured using a scale by Burris et al. (2008). Sample items include “My boss blames me to save himself/herself embarrassment,” and “My boss puts me down in front of others” with rating scale from (1) never to (5) always.

Job control and autonomy

Finally, job control affects communication as well. Job control varies within and between organizations, and it refers to the degree that an individual has a say in what they do at work and how their work gets done (Dwyer and Ganster, 1991). If a person has higher job control, this leads to better communication, because what people have to say actually has a clear impact on their workplace versus those with less job control.

Job control can be measured with a scale from Dwyer and Ganster (1991) that includes questions such as, “How much can you generally predict the amount of work you will have to do on any given day?” scored on a 5-point scale, ranging from (1) very little to (5) very much. Job control even includes questions like “how much are you able to decorate, rearrange, or personalize your work area?”

The impact of organizational culture on workplace communication is not entirely conclusive

Cultural variables certainly have an effect on communication, and they have been studied for decades. Although early researchers (e.g., Milliken, Morrison, and Hewlin, 2003) argued that culture affects communication, the role of culture is not entirely conclusive. Other researchers have argued that context plays less of a role than it is being given credit for and that internal beliefs about communication are formed outside of one’s current workplace. Therefore, beliefs about speaking up may be minimally related to current context (Detert & Edmondson, 2011).

Internal beliefs help us to quickly form opinions and act on them

Early social psychologists recognized that people’s internal beliefs, even if not held in the conscious mind, can play an important role in social understanding and behavior (Heider, 1958; Jones & Thibaut, 1958; Kelly, 1955). Internal beliefs contain assumptions about cause and effect (Anderson & Lindsay, 1998) that allow individuals to make predictions about the outcome of a situation or the behavior of a person, given the presence of certain characteristics (Levy, Chiu, & Hong, 2006).

By comparing new characteristics to previously encountered characteristics that are schematically stored in memory, individuals can quickly form an opinion and take action (Chiu, Hong, & Dweck, 1997) – largely because the decision-making process takes place outside of conscious awareness. A related concept appears in stereotype research, in which scholars have demonstrated how people form, use, and maintain stereotypes without conscious awareness (e.g., Fiske, 1998; Levy et al., 1998).

Internal beliefs are stable and tend to be resistant to external influences

As mentioned earlier, Detert and Edmondson (2011) explored the relationship between internal beliefs (referred to as implicit theories) and communication in the workplace. Similar to stereotyping processes, they found that silence in organizations is governed by a set of internal beliefs that are quickly activated upon encountering a familiar situation.

People’s internal beliefs tend to remain stable, despite changes in their environment like a new boss. According to the logic of our internal belief systems, a boss is a boss. There is little variability between them, so we do not behave as differently form one boss to the next as other research might suggest.

Problems can occur when people follow beliefs that may be appropriate for one boss or organization but not another organization. For example, if your first boss told you never to bring up a problem without a proposed solution, you might carry that belief to your next job where your boss will be upset that you failed to bring up a problem sooner.

In the literature, a bad experience with a boss left an individual holding the same internal beliefs about speaking up for 12 years and through three separate managers (Kish-Gephart et al., 2009). Like stereotypes driven by beliefs that inhibit variability in perceptions of others, it seems that internal beliefs might persist through multiple environments and multiple bosses. The possibility that individuals may form beliefs that persist in spite of cues from the current context is an issue that has been studied a great deal in the last 5-10 years, given the problems for individuals and organizations that can arise from a person following old internal rules that do not benefit the present situation.

Effective communication at work can be nurtured through an organizational culture that takes into account internal beliefs of employees

Understanding communication in the workplace requires an understanding of culture and internal belief systems. While leaders and coworkers can affect culture which ultimately affects communication, employees also bring existing beliefs to work about what is appropriate to say to their coworkers. These beliefs remain fairly stable as they move into different jobs, and they may not match the culture or needs of an organization. Therefore, in order to have a robust understanding of the drivers of communication, it is important to understand both cultural factors in the organization and also to understand internal beliefs that employees hold.

Key take-aways

- Workplace cultures that are psychologically safe encourage communication

- Organizations that are more bureaucratic and hierarchical discourage communication

- Leaders who are open and interested in subordinates’ thoughts create a culture that encourages communication

- Hostile bosses who blame subordinates for problems discourage communication

- The degree to which you have control over your job encourages communication

- Internal beliefs learned outside of the organization will affect communication behavior within the organization, irrespective of cultural influences

- Internal beliefs (also known as implicit theories) are very resistant to change and will persist from one job to the next

Refences and further readings

Anderson, C. A., & Lindsay, J. J. (1998). The development, perseverance, and change of naive theories. Social Cognition, 16, 8-30.

Burris, E. R., Detert, J. R., & Chiaburu, D. S. (2008). Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 912-922.

Chiu, C., Hong, Y, & Dweck, C.S. (1997). Lay dispositionism and implicit theories of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 19-3.

Detert, J. R. & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 869-884.

Detert, J. R. & Edmondson, A.C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: An emerging understanding of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 461-488.

Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., Lawrence, K. A., & Miner-Rubino, K. (2002). Red light, green light: Making sense of the organizational context for issue selling. Organization Science, 13, 355-369.

Dwyer, D.J. and Ganster, D.C. (1991). The Effects of Job Demands and Control on Employee Attendance and Satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 595-608.

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350-383.

Fiske, S. T. (1998). Stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination. In D.T. Gilbert, S.T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.) The Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 357-411) Boston: McGrawHill

Hage, J. & Aiken, M. (1969). Routine technology, social structure, and organizational goals. Administrative Science Quarterly, 14, 366-376.

Heider, F. (1958). The Psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, E. E. & Thibaut, J. W. (1958). Interaction goals as bases of inference in interpersonal perception.(In R. Tagiuri & L. Petrillo (Eds.), Person perception and interpersonal behavior. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 151-178.

Kish-Gephart, J., Detert, J.R., Trevino, L.K., & Edmondson, A.C. (2009). Silenced by fear: Psychological, social, and evolutionary drivers of voice behavior at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163-193.

Levy, S. R., Stroesser, S.J., & Dweck, C.S. (1998). Stereotype formation and endorsement: The role of implicit theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1421-1436.

Levy, S. R., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (2006). Lay theories and intergroup relations. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 9, 5-24.

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. 2003. An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don't communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1453-1476.

Needle, D. (2004). Business in Context: An Introduction to Business and Its Environment. Mason: South Western Educational Publishing

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178–190.

About the Author