- All Management Learning Resources

- Behavior change

Executive summary

How should you as a professional go about instituting new work processes or eradicating unproductive or bad habits in your organization, team or project? Research into the psychology of habitual behavior change can provide numerous insights. Neuroscientific research, in particular, has uncovered many tips for changing how a person behaves on a regular basis. Below are some of the latest, science-supported tips for eradicating bad workplace behavior, encouraging employees to adopt new habits, and making sure that those new habits “stick” long after the intervention has ended.

Contents

When is behavior change necessary?

“Micromanagement” has a bad reputation for a reason. When an employee or team member feels that their every move is examined and evaluated, they tend to feel on-edge, uncomfortable, and disrespected (Yamada, 2008). In most cases, focusing on the granular details of an employees’ productivity methods is a waste of time at best, and a means of eroding relationships at worst (Cleary, Hungerford, Lopez, & Cutcliffe, 2015). Generally, if an employee is getting the work done in an effective way that doesn’t make collaboration difficult or alienate their peers, it’s best for a professional to take a hands-off approach.

Breaking bad habits: When behavior starts to hurt performance

Of course, a hands-off approach to employee methods and behaviors is not always sufficient. You as a professional do play a crucial role in helping employees develop the workplace processes and habits that will guarantee success. And at times, employees may be caught in behavioral feedback loops or engaging in workflows that drain time and resources; in those cases, intervention is necessary (Graybiel & Smith, 2014).

How to break bad habits and initiative behavior change

Truly “bad” workplace habits are not just mildly annoying or unusual, they are disruptive, inconsiderate, or cause losses to team productivity or cohesion. As a manager, your first task is learning to differentiate between the tolerable or odd behavior, and bad habits that need to be broken (Pulakos et al, 2015). For example, an employee who needs to listen to music to complete a writing project can be easily accommodated, whereas an employee who talks loudly, starts side conversations, and distracts peers at their desks probably requires intervention. A team member who tends to ramble in meetings may be tolerable, but an employee who talks over other people, interrupts, and derails conversations probably needs to be addressed.

Make the individual aware of problematic behavior

Many bad workplace habits are unconscious, or relatively thoughtless. A good initial response, as a professional and manager, is to professionally and privately make the employee aware that the behavior is occurring. Use descriptive, illustrative language, and provide concrete examples (Ng, Feldman, & Butts, 2014). For example, you can say, “I have noticed that you stop by Karen’s desk to talk to her many times during the day. Yesterday, you talked to her for twenty minutes while she was working on a project.” In some cases, merely making an employee aware that they are engaging in problematic behavior (such as leaving a mess in the breakroom, or interrupting women in meetings) is sufficient to inspire change.

Convey consequences if behaviour change doesn't occur

Help your employees understand why a habit is problematic. Provide a few specific examples of a time when the behavior caused conflict, resulted in work errors, or harmed other people. Once the employee has a sense of why the habit is a problem, explain to them how you will respond if the behavior continues.

Provide alternatives to replace bad habits

Bad habits usually have to be replaced with new, more beneficial habits. In some cases, this may require working with the employee to determine what needs or desires they are seeking to meet with their current, unproductive habits (Spotswood et al, 2015). Together, you can determine alternate ways of meeting those needs that do not impact productivity in a negative way.

For example, if an employee interrupts people during presentations because he is worried his ideas will be forgotten or left unheard, he can begin writing down his ideas on a notepad, and can be invited to share a summary of thoughts at the end of the meeting. An employee who is hanging around in other workers’ spaces and irritating them may actually be seeking an opportunity to stretch her legs; she may be able to meet this need by using a standing desk or taking short walking breaks every two hours.

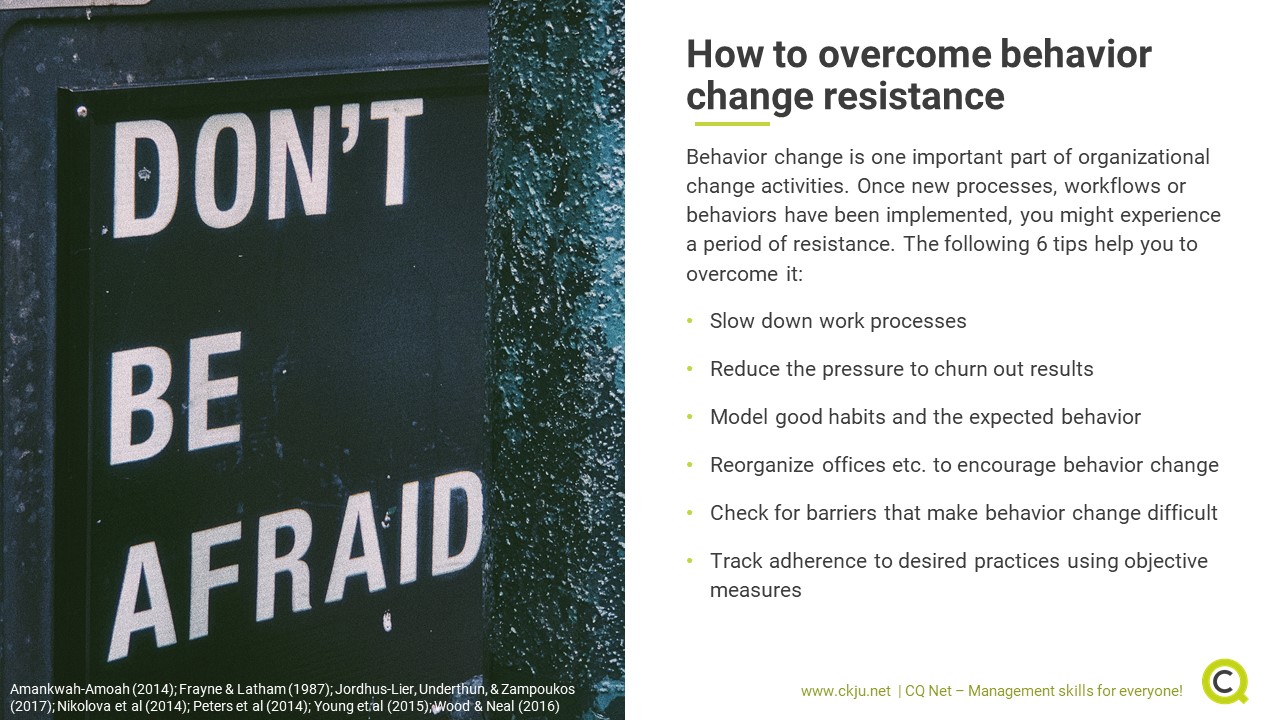

How to overcome behavior change resistance

Often, professionals and managers struggle to get employees to adopt new habits. However, shifting behavioral patterns is frequently part of a professionals job. Perhaps a new step has been added to an existing work process, or new habits must be adopted for the sake of improving outcomes. In either case, there will typically be a period of resistance, during which employees forget to engage in the behavior, find the behavior challenging, or even refuse to do it (Amankwah-Amoah, 2014). The science of behavior change, thankfully, can provide some pointers for opposing this resistance.

Management skills newsletter

Join our monthly newsletter to receive management tips, tricks and insights directly into your inbox!

Slow down processes

When a workflow has become fast-paced and automatic, employees struggle to make changes to it. It can be difficult to “break the flow” and add a new step, especially if an employee still feels pressure to complete work just as quickly as they did before the step was added. To combat this, and to help employees form new patterns, slow down the work process (Peters et al, 2014).

Reduce the pressure to churn out results

While a new habit is being introduced, reduce the pressure employees feel to churn out results. Walk everyone on a team through the individual steps that make up the new habit or process. Give employees time to reflect on how they do their work, and to sequence their steps. When employees are able to carefully observe their own actions and see all the individual “steps” in the process, they are more likely to make intentional, correct choices regarding their habits (Young et al, 2015).

Model good habits and expected behavior

Social modeling is powerful. Seeing other people engaging in a behavior, and benefitting from that behavior, can be more useful than instruction or practice alone (Frayne & Latham, 1987). To implement new work habits, try appointing a few employees to lead the charge. Train them in the new behaviors, so they can model those behaviors for their peers. These “model” employees can also answer questions, and help their compatriots trouble-shoot problems.

Reorganize to encourage behavior change

When an office has done work in a particular way for a long period of time, everything from the floor plan of the office to how people organize their desks reflects that way of doing business (Nikolova et al, 2014). Often, a new workflow or habit is not well suited to the old set-up, and changes may need to be made. Observe new work processes in action, and determine how to set up the office in a way that encourages the proper steps.

Check for barriers that make behavior change difficult

Observe your employees and determine what barriers, if any, are making adoption of new habits difficult (Jordhus-Lier, Underthun, & Zampoukos, 2017). Does work now go through different people, or in a different sequence, than it once did? Then you may want to rearrange the floor plan or furniture to account for this. Have work procedures changed? If so, the scheduling and timing of meetings and other events may need to shift to help everything “fall in place”. Ideally, you want the new habits and work flows to be the path of least resistance – the most natural-feeling option.

Track adherence to desired practices using objective measures

Over time, new habits may dissolve if individuals don’t take intentional steps to maintain them (Wood & Neal, 2016). As a manger, you should check in regularly to ensure that employees are sticking to the correct work behaviors, and aren’t slipping into counter-productive patterns. Re-training and refreshing knowledge in regular meetings or practice sessions can be very beneficial. Tracking adherence to desired practices using an objective measure can be also be helpful; review these benchmarks during regular meetings, and focus on improving team-wide adherence, rather than singling out individuals. Finally, persistence is key – most habits take at least a month or two to become second-nature. New work processes are no exception.

Key take-aways

- To combat negative workplace behavior, make employees aware of their bad habits and convey the impact of those habits in a measurable way.

- Provide alternative outlets for behavior or impulses that are negatively affecting the workplace.

- To introduce new work habits, slow down processes, and give employees models of what “good” behavior looks like.

- Unseen barriers within an organization may make adopting new habits difficult – search for these barriers and restructure the workplace accordingly.

- New habits take time to adopt, and employees should be re-trained in new procedures to help make them “stick”.

References and further reading

Amankwah-Amoah, J. (2014). Old habits die hard: A tale of two failed companies and unwanted inheritance. Journal of Business Research, 67(9), 1894-1903.

Cleary, M., Hungerford, C., Lopez, V., & Cutcliffe, J. R. (2015). Towards effective management in psychiatric-mental health nursing: The dangers and consequences of micromanagement. Issues in mental health nursing, 36(6), 424-429.

Frayne, C. A., & Latham, G. P. (1987). Application of social learning theory to employee self-management of attendance. Journal of applied psychology, 72(3), 387.

Graybiel, A. M., & Smith, K. S. (2014). Good habits, bad habits. Scientific American, 310(6), 38-43.

Jordhus-Lier, D., Underthun, A., & Zampoukos, K. (2017). Changing workplace geographies: Restructuring warehouse employment in the Oslo region. In Royal Geograhical Society with IBG, Annual International Conference, London, 30 augusti–1 september 2017.

Nikolova, I., Van Ruysseveldt, J., De Witte, H., & Syroit, J. (2014). Well-being in times of task restructuring: The buffering potential of workplace learning. Work & Stress, 28(3), 217-235.

Ng, T. W., Feldman, D. C., & Butts, M. M. (2014). Psychological contract breaches and employee voice behaviour: The moderating effects of changes in social relationships. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(4), 537-553.

Peters, P., Poutsma, E., Van der Heijden, B. I., Bakker, A. B., & Bruijn, T. D. (2014). Enjoying new ways to work: An HRM‐process approach to study flow. Human Resource Management, 53(2), 271-290.

Pulakos, E. D., Hanson, R. M., Arad, S., & Moye, N. (2015). Performance management can be fixed: An on-the-job experiential learning approach for complex behavior change. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 51-76.

Spotswood, F., Chatterton, T., Tapp, A., & Williams, D. (2015). Analysing cycling as a social practice: An empirical grounding for behaviour change. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 29, 22-33.

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2016). Healthy through habit: Interventions for initiating & maintaining health behavior change. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2(1), 71-83.

Yamada, D. C. (2008). Human dignity and American employment law. U. Rich. L. Rev., 43, 523.

Young, W., Davis, M., McNeill, I. M., Malhotra, B., Russell, S., Unsworth, K., & Clegg, C. W. (2015). Changing behaviour: successful environmental programmes in the workplace. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(8), 689-703.

About the Author