- Blog

- Nudging for better management

Contents

- From homo economicus to human beings: irrationality makes behavior unpredictable

- Nudges rely on human heuristics, cognitive shortcuts or rules of thumbs to steer behavior into an intended direction.

- Nudges work by influencing, limiting or eliminating the choices available to people

- “Nudge management” promises to help organizational efficiency and productivity with subtle changes

- Nudges in management largely focus on information at work and how it is made available to people

- Creating a workplace nudge is relatively simple, flexible, quick and cost-effective

- Nudging may help motivation but is not a solution for all problems

- More research is required to prove whether nudging increases efficiency

- The lesson is clear: subtle dynamics matter in organizations and should be taken into consideration

- Nudging should receive a dedicated space in any manager’s toolbox

- References and further reading

Successful management arguably involves constant re-evaluation and seeking of new methods when challenges arise. One of the most recent trends that has grabbed the attention of practitioners has been the idea of “nudging” in management. Based on a groundbreaking book in behavioral economics, “nudging management” promises to help solve organizational problems by relying on subtle “nudges” or shoves to behavior, which promise to better align worker behavior with organizational goals. What is nudging really about and is it a useful framework to adopt into the manager’s toolkit? In the following blogpost, we will consider what nudging can and cannot bring to the table.

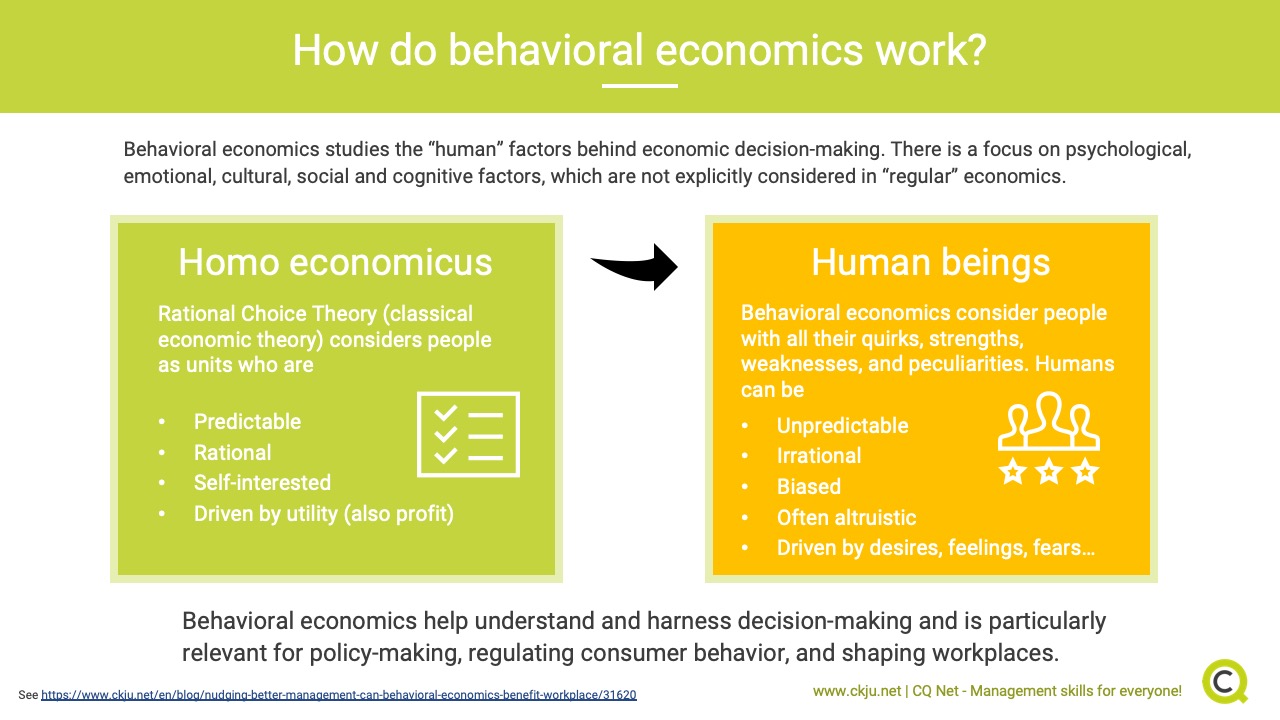

From homo economicus to human beings: irrationality makes behavior unpredictable

Classical economics relies on rational choice theory (RCT), ie. the idea that human beings are rational units who make decisions based on a clear-cut cost-benefit analysis, which prioritises the decisions that provide the most utility (i.e. profit). In other words, rationality means acting in untainted self-interest. Indeed, much of economic theory and other (often older traditions) in political science, philosophy and sociology rely on the idea of the so-called “homo economicus”, which has led to many mainstream theories and assumptions to reflect and replicate these assumptions.

Many RCT assumptions sound familar: a persons’ interest are reflective of their most likely actions, outcomes and choices can be predicted, circumstances only marginally affect decision-making, the collective will benefit if individuals behave rationally, etc. Like other disciplines, also management theory has been influenced by RCT.

Nudges rely on human heuristics, cognitive shortcuts or rules of thumbs to steer behavior into an intended direction.

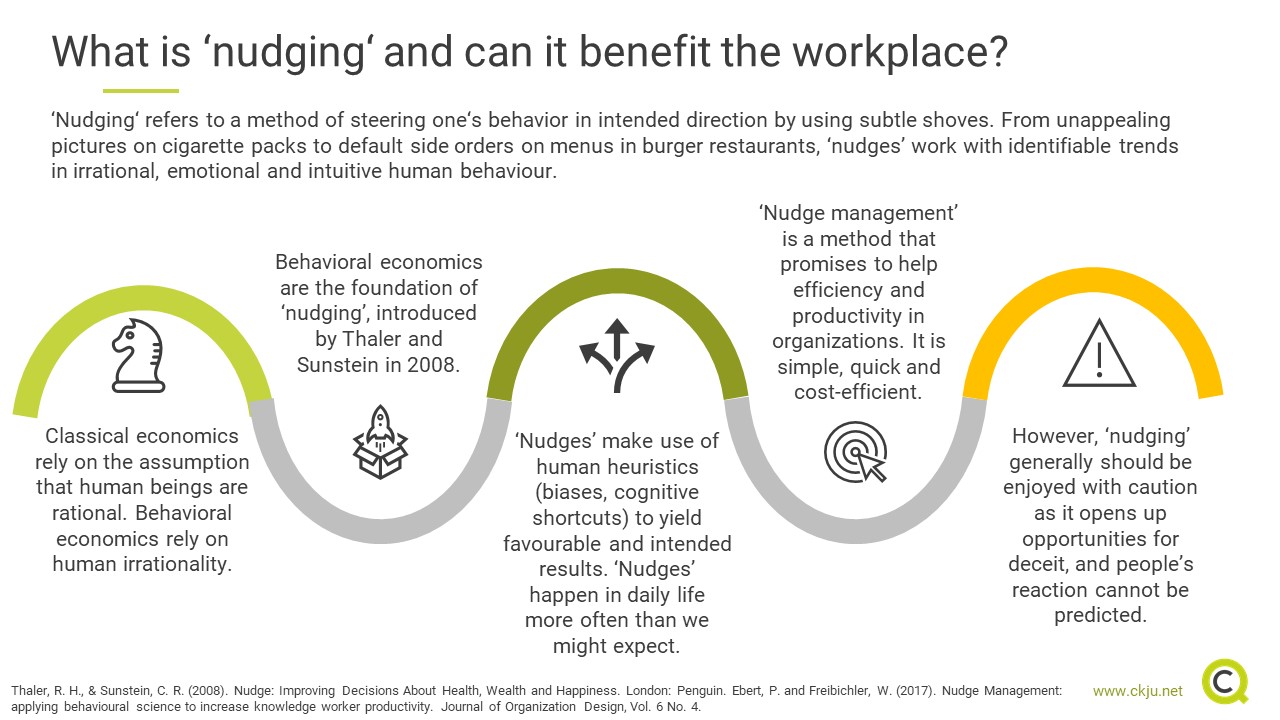

Over the past decades, the discipline of behavioral economics has gained more and more popularity and legitimacy. Radically departing from RCT, behavioral economics draws upon insights from psychology and the behavioral sciences to assess economic decision-making. One of its most vital contributions is the understanding that the human rationality assumed by RCT is “bounded” (i.e. limited).

For behavioral economists, rational choice theorists for rely on a too rigid conception of human nature, forgetting the element of irrationality that makes decision-making unpredictable. Instead, behavioral economists posit that humans are in fact irrational beings driven (at least to some extent) by emotion, intuition, and other behavioral patterns, which influence decision-making. However, as patterns can be identified and also show some consistency, they provide new opportunities for subtle interventions that can still yield intended outputs. In this vein, the idea of “nudging” was born.

Nudges work by influencing, limiting or eliminating the choices available to people

Originally introduced in a book by Thaler and Sunstein (2008), nudge theory builds on the idea that there are identifiable trends in this irrational, emotional and intuitive human behavior. These are commonly known as heuristics, cognitive shortcuts or rules of thumb that aid decision-making.

By understanding these patterns, subtle “nudges” can be developed and to steer behavior into the intended direction. Nudges can make use of heuristics and redirect them into an intended direction, thereby making use of the “shortcomings” of human behavior to yield favourable results. This works by influencing, limiting or eliminating the choices available to people.

Two simple examples highlight how nudges work in practice:

- A study on organ donation by Johnson and Goldstein (2003) showed that when people are required to opt-out of something, the rate of people who stays in a certain scheme is higher than when people are required to opt-in.

- Alternatively, when salad is the default side option to a burger at a restaurant, less people will order fries, which may be a more subtle initiative to improving public health than forbidding fries altogether.

Many different actors have serious interest in these insights and strategies, including marketing agencies but also governments and other public administration entities. For example, in 2010 the British Government introduced a Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) to improve policy and services.

“Nudge management” promises to help organizational efficiency and productivity with subtle changes

Some management approaches indeed already rely on behavioral insights to some extent: leadership development, rewards systems, competency models - these frameworks rely on the idea that human behavior deserves attention in successful management. In a new study, Ebert and Freibichler (2015) posit that nudge theory can and should be used to design organizational contexts that aid the knowledge worker: they term this “nudge management”.

Drawing from Peter Drucker, the authors conceive knowledge workers as those whose main asset/capital is knowledge over manual labour, arguably better reflecting the contemporary workforce. Ebert and Freibichler argue that with nudge theory, fast thinking and more efficient, goal-conducive behavior can be invoked. Indeed, previous research confirms that “whether you’re part of a large organization or a small, you may be thoughtful about the environment you create“ (Bock, 2015, p. 317).

Kröning Mogensen and Christiansen (2017, p.83) found that with the rise of new demands for fast, flexible and cost-effective methods for change-making in organizations, nudge theory has emerged as a potential strategy to help manage the new, self-managing knowledge worker.

Nudges in management largely focus on information at work and how it is made available to people

Ebert and Freibichler offer several concrete examples of how nudging can help productivity in the organization. Comparable to other research on human behavior at the workplace, their focus is largely on the manner in which information is provided to employees in the workplace. Information is identified as an easily accessible and already existing resource. Their suggestions seem simple (2017: p. 4):

- by setting the time for meetings lower (30 instead of 60 minutes) and starting the agenda with each employee giving feedback on the circulated documents, productivity and efficiency is increased.

- long-term planning can be improved through introducing “implementation intentions”, openly communited commitments, objectives and targets to ensure increased accountability and work ethic.

- task efficiency can be improved through providing a framework for “deep work” and concentration, for example through introducing a “no-meeting” day.

- knowledge sharing and communication can be facilitated through enabling regular encounters between employees in “micro kitchens”, equipped with healthy snacks and a comfortable environment (most famously, Google is a proponent of this method).

Other ideas along these lines could thus also include displaying visual reminders of past successes to increase motivation, or creating separate areas for “planning” or “research” that help workers focus. Indeed, recent and ongoing research at the University of Utrecht confirms similar insights: “It turns out that the way [a situation] is communicated to employees and the type of information provided to them can have an important effect on the quality of ideas that are submitted.” (Rigtering & Weitzel, 2016).

Creating a workplace nudge is relatively simple, flexible, quick and cost-effective

As is evident from these examples, creating a workplace nudge is relatively simple, flexible, quick and cost-effective compared to other management interventions. Halpern (2015) identifies four markers that define a successful nudge: they must be easy (attainable), attractive (grasp attention), social (make use of networks) and attainable (immediate).

Indeed, these four markers sum up very well the general characteristics of nudges. Nudges are

- easy-to-implement

- intriguing

- friendly

- feasible

- subtle

As such, they are great methods to help foster and improve organizational culture. In the words of Ebert and Freibichler, nudging management is a “new, exciting opportunity to improve (knowledge) worker productivity by focusing on and refining the organizational context that influence fast thinking to improve efficiency, effectiveness and motivation” (p. 6).

Nudging may help motivation but is not a solution for all problems

Despite this undoubtedly promising and simple, straightforward strategy, there are some aspects to consider that tend to be downplayed in popular management discourses.

Nudging can be abused very easily and should always be used with good intentions to improve welfare

Nudging is a technique that opens up a breadth of opportunity for deceit and manipulation, as it can be (ab)used very easily. While most managers might not have an interest in this, making use of innate heuristics for a certain goal may interfere with people’s freedom of choice in unintended ways. Thaler, one of the two professors behind nudge theory, himself outlined three principles of nudging: nudges should be transparent and never misleading, easy to opt out of, and should be used for improving the welfare of those nudged (Thaler, 2015).

People are people and nobody can fully predict how they will respond

Under no circumstances can it be predicted how people respond, whether the outcomes are the intended ones, or whether the nudges work in the first place. Similar to rational choice theory which views people as rational units, behavioral economics equally works with preconceived notions of the human psyche, which may not always be fruitful and may have detrimental effects. In fact, recent research shows that nudging may not work for some people at all, as a person's individual decision-making process influences whether or not nudging even works (Benkert & Netzer, 2018).

Context matters - while nudging works in one scenario, it might not work in another

It makes sense to keep in mind contextual differences pertaining not only to organizations, but also to differences in work culture or general culture. Nudges may not be a one-size-fits-all solution for all problems, and are also unlikely to apply to all contexts equally.

More research is required to prove whether nudging increases efficiency

Most importantly for this piece, van Deun et al. (2018, p. 21) in their comprehensive literature review of over 300 articles about nudging in public management find that “evidence is inconclusive at best when it comes to measurable efficiency”. While it is true that there is little attention to mechanisms that drive human behavior in more traditional management theory, the authors state that nudging literature often refers to anecdotal results, rather than evidence-based ones. The applicability and success of nudges seems to be taken as a given and is not subject to scientific scrutiny, the authors point out. As such, nudging more generally should be scrutinized and researched critically.

The lesson is clear: subtle dynamics matter in organizations and should be taken into consideration

Although nudge theory has been subject to criticism, taking a “nudge-view” informed by behavioral insights allows for important take-aways about organizations, which can be of use for managers and working professionals alike without making use of “nudges” directly.

Organizations are driven by interactions, relationships, procedures and human behavior

Organizations can be governed by very subtle aspects, which with classical management tools may not always be considered. Particularly the importance of information, the manner in which it is conveyed and presented, and the environment in which information exchange takes place matters for efficient and productive work. Kinley & Ben-Hur (2015 p.2) clearly state that “managers need to include insights from psychology and behavioral economics to shape the environment in which decisions are made if they want to become more efficient in realizing organizational transformation”.

A healthy workplace culture can develop by initiating and steering good-decision making

Emotional and intuitive behavior reminds us that rather than forcing good decisions, humans value incentives, positive reinforcement, communication and positivity, which all can yield more sustainable results. In the words of Grunwald, Hammermann and Placke (2017, p. 154), “it is not possible to force good decisions, but rather initiate them”. Regulations often put a vision over the process of getting there and do not allow for a healthy workplace culture to develop.

Nurturing organizational culture is vital for performance, particularly in agile organizations

Just as much as managers are leaders, they are also coaches with the capacity to educate employees and to help them reach their potential. In this vein, rather than investing in costly methods to increase efficiency and productivity, it makes sense to establish a dynamic culture of open communication, feedback loops and re-evaluation of working methods and openly take into account shortcomings in human behavior. This way, needs can be voiced, problems discussed and interventions commonly agreed upon. In fact, new research points out that nudging may be a particularly vital lever in agile organizations, helping communication and creativity (Dianoux et al., 2019).

Nudging should receive a dedicated space in any manager’s toolbox

Thaler and Sunstein’s nudge theory most certainly brings vital insights to contemporary management. However, as is the case with any theory, critical reflection and re-evaluation is crucial to ensure that goodwill does not fall victim to unintended consequences. While nudging promises a cost-effective way to align individual behavior with organizational goals, it also raises questions about ethics, applicability and scientific value. However, the behavioral insights on heuristics, emotions, intuition and the implied “bounded” rationality are valuable aspects to consider in collaborative workplaces and should definitely receive a dedicated space in any manager’s toolbox (Kröning Mogensen and Christiansen, 2017, p. 57)

References and further reading

Benkert, J. M. and Netzer, N. (2018). Informational Requirements of Nudging. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 126 No. 6, pp 2323.

Bock, l. (2015). Work Rules. John Murrey.

Dianoux, C., Heitz-Spahn, S., Siandou-Martin, B., Thevenot, G., and Yildiz, H. (2019). Nudge: A Relevant Communication Tool Adapted for Agile Innovation. Journal of Innovation Economics & Management, Vol 1 No. 28, p. 7-27.

Ebert, P. and Freibichler, W. (2017). Nudge Management: applying behavioural science to increase knowledge worker productivity. Journal of Organization Design, Vol. 6 No. 4.

Foster, L. (2017). Applying behavioural insights to organisations: Theoretical underpinnings. OECD. Paper prepared as background document to the OECD European Commission seminar on “applying Behavioural insights and organizational behaviour” in May 2017 at OECD Headquarters in Paris, France.

Grunwald, A., Hammermann, A. and Placke, B. (2017). Human Resource Management and Nudging: An Experimental Analysis on Goal Settings in German Companies. International Journal of Economics and Finance, Vol. 9 No. 9, pp. 147-156.

Halpern, D. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How Small Changes Can Make A Big Difference. Ebury Press.

Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. G. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, Vol. 302, pp. 1338-1339.

Kinley, N. and Ben-Hur, S. (2015). Changing Employee Behaviour - a Practical Guide for Managers. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kröning Mogensen, A. B. and Christiansen, S. N. (2017). Nudging Organisational Change: Why and When is it Relevant? Master thesis, Copenhagen Business School.

Thaler, R. H. (2015). The Power of Nudges, for Good and Bad. The UpShot. New York Times. Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/01/upshot/the-power-of-nudges-for-good-and-bad.html.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. London: Penguin.

Van Deun, H., van Acker, W., Fobé, E., Brans, M. (2018). Nudging in public policy and public management: a scoping review of the literature. presented at the PSA 68th Annual International Conference, Cardiff University, United Kingdom.

Top Rated

About the Author

Comments

Most Read Articles

Blog Categories

RELATED SERVICES

Add comment