- All Management Learning Resources

- Situational awareness

Executive summary

Situational Awareness is a concept that has been around in aviation, healthcare and the military for many years. The benefits associated with situational awareness are significant with an increase in safety, task, team and organizational performance as the most important outcomes. We have a look how it can be used as management tool in the private and public sector in this CQ Dossier. Our focus will be on the foundations of situational awareness, the three level model, and measures how to improve situational awareness in a particular setting.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Situational awareness in the area of error prevention and performance improvement

- What is situational awareness?

- Situational awareness in project management

- Situational awareness in operations

- Situational awareness and continuous improvement

- The three-level model of situational awareness: Perceiving, understanding and predicting

- What benefits are associated with situational awareness?

- How to improve situational awareness?

- Critical appraisal of situational awareness: Solidity rating 4

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

Situational awareness in the area of error prevention and performance improvement

Human error a natural part of organizational life. In a safe environment errors can be a source of inspiration, a driver of learning and even a spark for innovation. However, in many situations human errors do more harm than good and should thus be reduced to a minimum or completely avoided at all. This especially applies to healthcare, aviation and other high-risk sectors where errors can have severe consequences. In other organizations, errors or other unexpected deviations can undermine organizational performance.

The concept of situational awareness has been around for many years. In that time, both scholars and practitioners confirmed the benefits associated with situational awareness in the area of error prevention and performance improvement (Brady et al. 2013; Stanton et al. 2006). Regardless of whether you are in the private or public sector, having such a management tool at hand is an important asset for your professional development.

What is situational awareness?

One of the key concepts of situational awareness is the distinction between a person (or system) and the environment. The environment refers to everything important that is going on around a person. A focus on important elements of the environment emphasizes that situational awareness is always about getting someting done. This can be a task, a project or anything else that requires interaction with relevant elements of the person's environment.

Situational awareness distinguishes between person and environment

In the aviation industry the environment of a pilot is the aircraft (cockpit), the weather and traffic situation as well as the air traffic controller the pilot is in contact with. In the business sector, the environment of a project manager is the project team, internal and external stakeholders, the project progress and all relevant project stakeholders (e.g. steering committee, customers, regulators) he or she has to deal with in order to achieve the project objective.

Situational awareness is about knowing what is going on in the environment

On the most basic level, situational awareness is about knowing what is going on in the environment and its implications for the present and the future (Endsley 1988). While this might sound straightforward in a stable and simple situation, it can become a real challenge in a fast paced and complex environment. This makes situational awareness a concept that is especially relevant for situations characterized by a high level of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA).

Situational awareness in project management

There is almost no project without deviations. The source of project deviations can be a change of customer requirements, unforeseen issues during implementation phase or simply mistakes that can lead to time and cost overruns. The earlier deviations are recognized, the smaller their impact is on the project progress. As a project manager, a high level of situational awareness can make your life much easier as you are able to avoid issues from the very beginning.

Situational awareness in operations

Reaching a high level of safety, productivity and quality is one of the most important objectives in operations. Whether it is in supply chain management, manufacturing or server administration, you need to be aware of the full picture to avoid accidents, a loss of productivity or service disruptions.

For instance, recognizing an attack on your IT infrastructure as early as possible can tremendously reduce to risk of unplanned downtime. The same applies to an unsafe situation on a manufacturing plant shopfloor. A high level of situational awareness ensures that unsafe situations are recognized as critical, are addressed, and that countermeasures are implemented.

Situational awareness and continuous improvement

One of the key objectives of situational awareness is error identification and prevention. In a similar way situational awareness can contribute to the continuous improvement process in teams and organizations on two levels.

First, improved situational awareness can help to identify issues before negative consequences emerge. Second, the concept helps to go through a structured learning process and identify situations which could have been avoided with a proper level of situational awareness. This makes situational awareness a management tool to drive organizational learning.

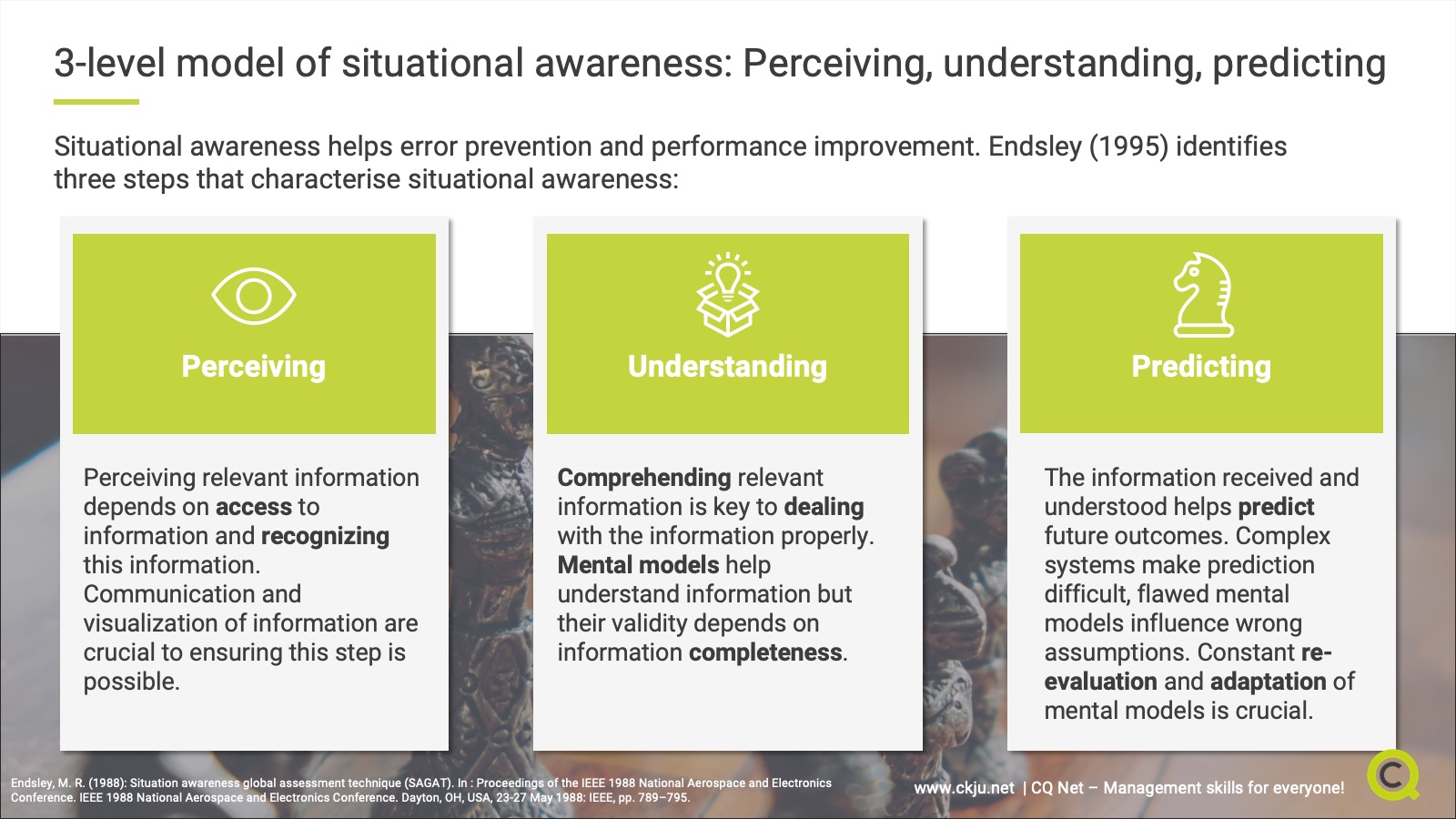

The three-level model of situational awareness: Perceiving, understanding and predicting

Various models of situational awareness have been developed (Stanton et al. 2017). The most popular and from our point of view most practicable one is the three-level model from Endsley (1995):

Level 1 SA: Perceiving

The first level of situational awareness is about perceiving the relevant information. This has two important implications. First, the person must have access to the relevant information. Seconds, once access is in place, the person has to recognize it. Consequently, one of the key requirements of level 1 SA is communication and proper visualization.

For instance, when a project manager isn’t informed about an issue that is going to cause a project delay, he can’t initiate countermeasures to mitigate it. As a consequence, he lacks level 1 SA which makes it hard to make the right decisions moving on with the project in the right direction.

Interestingly, level 1 SA seems to be one of the key contributors of accidents in the healthcare and aviation sector. For instance, Schulz et al. (2015) found that of 200 critical incidents in anesthesia, 163 were related to a breakdown in SA with the biggest portion in level 1 (38%). Jones and Endsley (1996) come to a similar conclusion in their analysis of aviation accidents.

Level 2 SA: Comprehending

The second level of situational awareness refers to the requirement to properly comprehend the relevant information. Depending on the specific situation, this requires the right knowledge to deal with the acquired information. Mental models play an important role in level 2 SA (Jones and Endsley 1996).

This is because the person creates a new mental model or updates an existing one based on how the information is interpreted. When there is anything important missing or the information is incorrect, the mental model is flawed. As a consequence, the person experiences a breakdown on level 2 SA.

An example of level 2 SA is a project manager who is informed about a delayed project deliverable. Having in mind the overall project schedule, the project manager updates his mental model about the project status based on the newly received information.

Jones and Endsley (1996) and Schulz et al. (2015) identified Level 2 SA issues as the second most important reason for incidents. Examples include a lack of knowledge how to operate equipment, wrong assumptions how to operate it or simply errors in the way procedures are implemented.

Level 3 SA: Predicting

The last and final level 3 SA refers to predicting the future state based on the information perceived and comprehended. This is especially critical when dynamic processes are projected into the future based on wrong assumptions. For instance, complex systems are characterized by a high level of interdependencies. This makes it hard to predict how changes in one variable might influence the overall system state. Wrong or not up-to-date mental models are another source of level 3 SA breakdown.

In our project management example, level 3 SA refers to the project manager’s projection of the current project status into the future. This requires him to consider how deliverables, project delays, and other relevant issues impact the overall project progress. Furthermore, he will decide whether the project should be implemented as planned or countermeasures to get back on track are required.

What benefits are associated with situational awareness?

There are many benefits associated with situational awareness. First, situational awareness is important to prevent errors and deviations. There is a wealth of research that confirms this claim. For instance, Goldenhar et al. (2013) and Brady et al. (2013) implemented a set of measures to increase situational awareness in a quaternary care children’s hospital. As a result, the level of unrecognized situation awareness failure event (UNSAFE) was significantly reduced.

There is also a wealth on research about how a breakdown in situational awareness contributes to human errors (Situational Awareness and Patient Safety 2017). Consequently, measures to improve situational awareness are associated with an increase in safety performance.

The same applies to task performance. Situational awareness is an important prerequisite to identify what needs to be done in order to perform a task in a complex and dynamic environment. This makes it an important element of agility and agile leadership. Only when you continuously align your activities with environmental changes and implementation progress will you achieve your desired objective.

How to improve situational awareness?

Situational awareness can be improved (Drake 2018). We will have a look at some measures that help you to increase situational awareness and benefit from it.

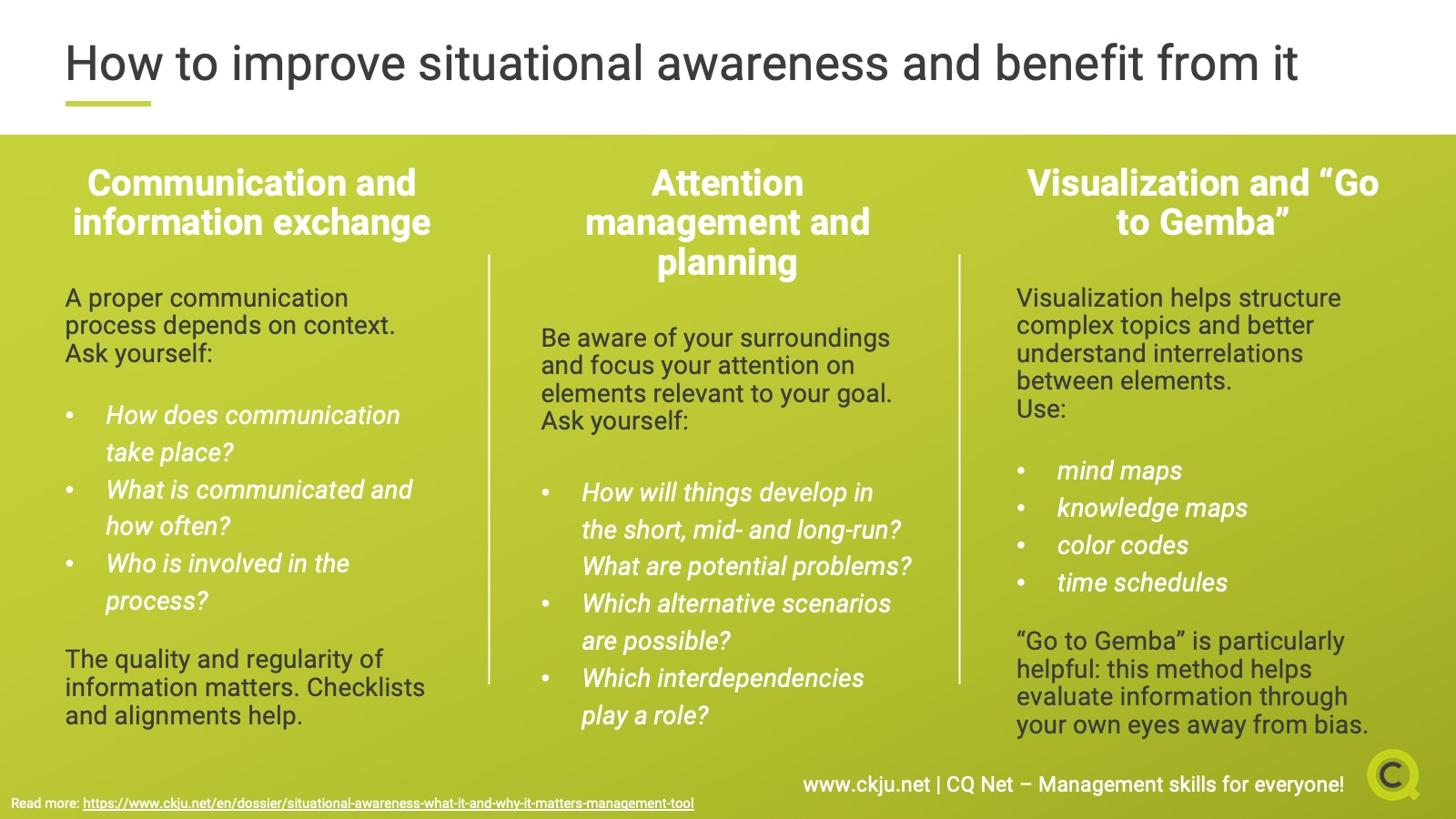

Proper communication and information exchange

A key prerequisite of situational awareness is proper communication and information exchange (Eduardo Salas et al. 2015, Stanton et al. 2017). However, there is no one size fits all approach but the need to tailor the way communication takes place to the specific context. The following key questions provide you an indication which factors should be considered when setting up a proper communication process:

- How does communication take place?

- What is communicated?

- How often does communication take place?

- Who is involved in the communication process?

An important point is that it is not about the communication quantity but its quality. The more complex an environment, the more frequent communication is required to keep situational awareness high. But this doesn't necessarily mean that the quantity of communication has to be high as well.

In many cases, short alignment or "huddles" (Goldenhar et al. 2013) are enough to make sure that you stay up to date on relevant changes. Another practical example of a communication tool that fosters situational awareness are checklists.

For instance, in a study in an healthcare emergency department Mullan et al. (2015) found that the introduction of a shift handoff checklist had a positive effect on safety, situational awareness, communication and effective care.

Attention management and planning

Situational awareness is about knowing what is going on around you. This requires you to continuously watch out what is going on in the environment. However, you can’t pay attention to every single detail. Instead you need to focus on those elements that are important to achieve a certain task or objective. Cognitive management (O'Brien and O'Hare 2007) is about actively managing your attention in a way such it is directed towards the most important elements based on their priority.

There is some evidence (O'Brien and O'Hare 2007) that when this prioritization process is combined with a planning process, situational awareness improves further. This can be achieved by asking the following questions:

- How will things develop In the short, mid long run?

- Which alternative scenarios can happen?

- Which problems/issues can arise in the short, mid and long run?

- Which interdependencies do play a role in how things might evolve?

Visualization and ‘Go to Gemba’

A special form of communication and information exchange is visualization and Go to Gemba. Visualization helps to structure complex topics, recognize deviations and better understand how single elements are related to each other. There are various visualization tools and methodologies that you can easily use in any type of organization:

- Different forms of maps such as mind maps, knowledge maps

- Color codes that indicate special areas, functionality or risks

- Time schedules with important milestones

Go to Gemba is a tool that has its origin in lean management and refers to being where things happen. The main point of Go to Gemba is that you can only recognize an issue to its full extend when you see it with your own eyes. One of the key assumptions behind this approach is that all information you don’t get firsthand is somehow biased, incomplete or lacking detail. As a consequence, you need to have a look at the issue with your own eyes to really know what is going on. This makes Go to Gemba a method to improve situational awareness.

Critical appraisal of situational awareness: Solidity rating 4

Based on the empirical evidence for the importance of situational awareness, this Dossier is assigned a Level 4 rating (based on a 1- 5 measurement scale). A level 4 is the second highest rating score for a Dossier based on the evidence provided on the importance of situational awareness. To date, the research on situational awareness has demonstrated the importance of this construct and has demonstrated the positive outcomes associated with it. However, even though a variety of empirical studies confirm the positive outcomes of situational awareness, there is still a lack of meta-analyses supporting the claims made.

Key take-aways

- Situational awareness is about knowing what is going on around you

- In its core, situational awareness distinguishes between a person and the environment

- One of the most prominent situational awareness models distinguishes between three different levels

- The first level of situational awareness is about perceiving the relevant information

- The second level of situational awareness refers to the requirement to properly comprehend the relevant information

- The third and final level of situationnal awareness refers to predicting the future state based on the information perceived and comprehended

- Measures to improve situational awareness are associated with an increase in safety and task performance

References and further reading

Brady, Patrick W.; Muething, Stephen; Kotagal, Uma; Ashby, Marshall; Gallagher, Regan; Hall, Dawn et al. (2013): Improving situation awareness to reduce unrecognized clinical deterioration and serious safety events. In Pediatrics 131 (1), e298-308. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-1364.

Drake, Kirsten (2018): How to hone situational awareness. In Nursing management 49 (6), p. 56. DOI: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000533778.45038.38.

Eduardo Salas; Carolyn Prince; David P. Baker; Lisa Shrestha: Situation Awareness in Team Performance: Implications for Measurement and Training. In Hum Factors 1995 (37(1)), pp. 123–136.

Endsley, M. R. (1988): Situation awareness global assessment technique (SAGAT). In : Proceedings of the IEEE 1988 National Aerospace and Electronics Conference. IEEE 1988 National Aerospace and Electronics Conference. Dayton, OH, USA, 23-27 May 1988: IEEE, pp. 789–795.

Endsley, Mica R. (1995): Measurement of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems. In Hum Factors 37 (1), pp. 65–84. DOI: 10.1518/001872095779049499.

Goldenhar, Linda M.; Brady, Patrick W.; Sutcliffe, Kathleen M.; Muething, Stephen E. (2013): Huddling for high reliability and situation awareness. In BMJ quality & safety 22 (11), pp. 899–906. DOI: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001467.

Jones, Debra; Endsley, Mica (1996): Sources of situation awareness errors in aviation. In Aviation, space, and environmental medicine 67, pp. 507–512.

Mullan, Paul C.; Macias, Charles G.; Hsu, Deborah; Alam, Sartaj; Patel, Binita (2015): A Novel Briefing Checklist at Shift Handoff in an Emergency Department Improves Situational Awareness and Safety Event Identification. In Pediatric Emergency Care 31 (4), pp. 231–238. DOI: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000194.

O'Brien, K. S.; O'Hare, D. (2007): Situational awareness ability and cognitive skills training in a complex real-world task. In Ergonomics 50 (7), pp. 1064–1091. DOI: 10.1080/00140130701276640.

Robert R. Hoffman; Beth Crandall; Nigel Shadbolt: Use of the Critical Decision Method to Elicit Expert Knowledge: A Case Study in the Methodology of Cognitive Task Analysis.

Salas, Eduardo; DiazGranados, Deborah; Klein, Cameron; Burke, C. Shawn; Stagl, Kevin C.; Goodwin, Gerald F.; Halpin, Stanley M. (2008): Does team training improve team performance? A meta-analysis. In Human factors 50 (6), pp. 903–933. DOI: 10.1518/001872008X375009.

Salas, Eduardo; Dietz, Aaron S. (2011): Situational awareness. Farnham England, Burlington VT: Ashgate (Critical essays on human factors in aviation).

Schulz, Christian M.; Krautheim, Veronika; Hackemann, Annika; Kreuzer, Matthias; Kochs, Eberhard F.; Wagner, Klaus J. (2015): Situation awareness errors in anesthesia and critical care in 200 cases of a critical incident reporting system. In BMC Anesthesiol 16 (1), p. 729. DOI: 10.1186/s12871-016-0172-7.

Situational Awareness and Patient Safety (2017). In AORN journal 106 (5), pp. 433–468.

Stanton, N. A.; Salmon, P. M.; Walker, G. H.; Salas, E.; Hancock, P. A. (2017): State-of-science: situation awareness in individuals, teams and systems. In Ergonomics 60 (4), pp. 449–466. DOI: 10.1080/00140139.2017.1278796.

Stanton, N. A.; Stewart, R.; Harris, D.; Houghton, R. J.; Baber, C.; McMaster, R. et al. (2006): Distributed situation awareness in dynamic systems: theoretical development and application of an ergonomics methodology. In Ergonomics 49 (12-13), pp. 1288–1311. DOI: 10.1080/00140130600612762.

About the Author