- Blog

- AI in the workplace

Contents

- This time it's different: AI brings many benefits for the workplace

- AI is changing the workplace as we know it

- AI disrupts the workforce: what is hype and what is reality?

- Research findings on the impact of AI on unemployment vary

- AI is rapidly advancing as computerization starts to permeate cognitive domains

- There are many tasks that are still beyond the reach of AI

- The skills of the future are a combination of interpersonal and cognitive skills

- Managers must prepare organizations for upcoming disruptions to work

- References and further reading

This time it's different: AI brings many benefits for the workplace

Recent PwC research (Rao & Verweij, 2017) shows that global GDP could increase by up to 14% by 2030 as a result of productivity, efficiency, and accuracy gains and lower costs brought by AI. This is the equivalent of an additional $15.7 trillion, about half of which would be in operational savings, but the other half would come from opening up new markets, new products, and new businesses.

People have been intensively competing with machines since the Industrial Revolution more than 250 years ago. However, unlike prior waves of technological advancements that have primarily affected so-called blue-collar jobs, the latest strides in AI threaten to impact all levels of employment and management.

Another remarkable difference is the rate of change – the impact of previous technological breakthroughs played out over decades, leaving enough time for people to develop new skills and adapt.

AI is changing the workplace as we know it

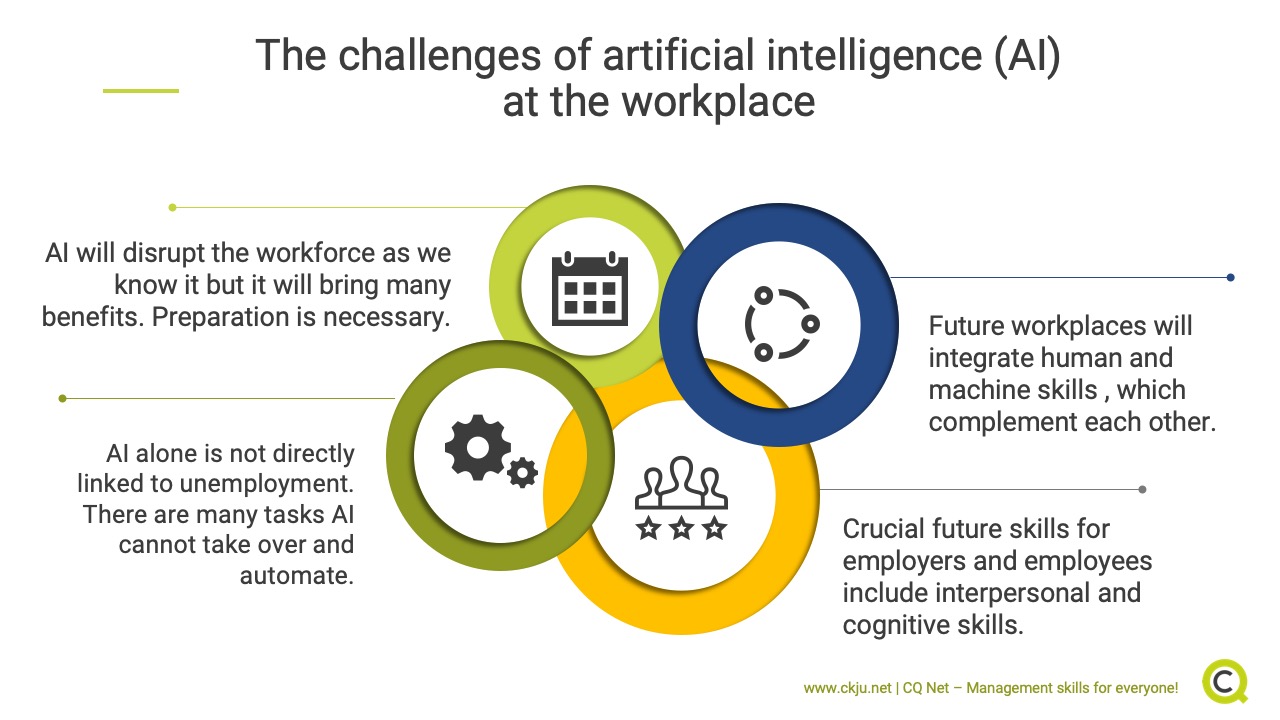

Although the effects of the AI on the workplace have been subtle so far, its capabilities are evolving extremely rapidly, and the scale of the change is starting to become apparent. The technology is expected to affect every sector by the end of the decade. Work will be transformed, but not every job is at equal risk - some are more vulnerable to disruption, others less so.

The workplace of the future will need to integrate the capabilities of humans who see the big picture and have interpersonal skills, and machines that will continue to do the computational work they do well. Dellermann et al., (2019) argue that the most likely division of labor between humans and machines in the next decades is hybrid intelligence which aims at using the complementary strengths of human intelligence and AI to act more intelligently than each of the two could be separately.

For example, an automated diagnostic method achieved a 92% success rate in identifying the presence of lymph nodes cancer and a human pathologist scored 96%, while the combination of human and machine yielded a 99.5% success rate (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 2016).

This will mean people will need to work alongside AI and algorithms. Managers will need to manage these teams effectively, bringing the new dimension to the meaning of diversity.

AI disrupts the workforce: what is hype and what is reality?

A new generation of labor, called the human intelligence of artificial intelligence, will emerge as the key factor for enterprises to survive in this changing environment (Ertel, 2018). But the workforce needs to be reskilled to exploit AI rather than compete with it.

While widely cited headline-grabbing estimate that 85% of the jobs that today’s primary aged children will hold do not exist now, turned out to be ungrounded (Newton, 2018) and overstated, it is reasonable to expect that we will need new hybrid-skilled knowledge workers who can operate in jobs that have never existed before, capable of adapting to new processes, systems and tools every few years (Pew Research Center, 2018).

Research findings on the impact of AI on unemployment vary

Technology can create extraordinary value, but it often does so through a highly disruptive process, creating benefits in the long term, but significant dislocations in the short term. The extent of the impact is hard to predict, with studies documenting varying results within a considerable range.

When widely-cited initial research (Frey and Osborne, 2013) estimated that 47% of total US employment fell into the 'high risk of automation' category, it prompted an intense public debate that followed. This encouraged researchers to explore the issue further, resulting in differentiation between AI’s impact on individual activities and complete occupations, which mostly yielded weaker effects of AI (The British Academy & The Royal Society, 2019).

AI is rapidly advancing as computerization starts to permeate cognitive domains

AI slowly but surely spreads into the realm once considered exclusive to humans. Computers can now read emotions from facial expressions, recognize the voice, understand written text, and write themselves. How did this happen?

Knowledge work automation, or automation of tasks that consists of sophisticated analyses, subtle judgments, and creative problem solving became possible by advances in three areas:

- computing technology,

- machine learning, and

- natural user interfaces such as speech/voice/image recognition technology.

With smartphones becoming a staple in the modern age, connected products and the expansion of the Internet of Things, and increasing digitization of everything around us, we are leaving an immense digital footprint behind us in our day to day lives – and it’s growing. This is what Big Data is.

Then, strides in computer power (doubling every two years on a price/performance basis), data storage systems and cloud computing, allow this immense amount of digital data to be feed into algorithms that learn and get smarter as they go along. The more they process big data, the more refined the algorithms become.

The machines now learn, and here lies the fundamental difference. As Goldin and Katz (2009) explain, the reason why human labor has prevailed during previous technological shifts relates to its ability to adapt and acquire new skills through education and learning. However, as the computerization increasingly permeates cognitive domains, this will become increasingly challenging (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2012).

There are many tasks that are still beyond the reach of AI

The engineering becomes increasingly better at unbundling various occupations into simple tasks to make them automatable, but it still fails to make a breakthrough in the following areas (Frey and Osborne, 2013):

Perception and manipulation tasks

Computers still don’t have depth and breadth of human perception and are still clumsy at these tasks, especially those that require precision or those relating to an unstructured work environment.

Creative intelligence tasks

Creativity is a novelty, coupled with values. Generating novelty proved not particularly difficult for computers. Instead, the main hurdle to computerizing creativity is stating our creative values sufficiently clearly (what humans think is beautiful or creative) so that they can be encoded in an algorithm. Besides, human values change over time, making it even harder to encode them. For now, it seems unlikely that occupations requiring a high degree of creative intelligence will be automated in the next decades.

Social intelligence tasks

Human social intelligence is essential for conducting tasks such as negotiation, persuasion, and care. Researchers within the fields of Affective Computing (also called Artificial Emotional Intelligence) and Social Robotics are trying to computerize these tasks, but computers are still mostly bad at this.

The reason is that human brains use an immense amount of 'common sense' information during even the simplest of social interaction. This is difficult to articulate and feed into algorithms to make computers function seamlessly in social settings (yet). The whole brain emulation - the scanning, mapping and digitalizing of a human brain is currently only a theoretical technology in this field, which if happens, will have an immense impact on employment, and life in general.

The skills of the future are a combination of interpersonal and cognitive skills

There is little chance for humans to outsmart computers, as many of those who play chess with machines are already aware. The new workers and managers should not bet their money on this if they were to thrive in the future workplace. Instead, they should aim to outhuman the increasingly humanized Artificial Intelligence. As Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2012) describe - fortunately, humans are strongest exactly where computers are weak, creating a potentially beautiful partnership.

Somewhat unexpectedly, the net effect of AI proliferation into the workplace may well be that it will make the people and the workplace more – human - as this is the unique value proposition people bring to the table in the work of the future.

Recent research (Bakhshi et al., 2018) finds that the skills of the future are the combination of

- Interpersonal (social)

- Cognitive skills: system skills, judgment and decision-making, systems analysis and systems evaluation

Managers must prepare organizations for upcoming disruptions to work

AI creates opportunities for growth, though with one essential caveat – that the education and training systems are agile enough to respond appropriately (Bakhshi et al., 2018).

Decision-makers within organizations and society as a whole need to acknowledge this to harness the full growth potential, rather than ignore it, risking a backlash against technology.

References and further reading

Bakhshi H., Downing J.M. & Osborne M.A., Schneider P. (2018) The Future of Skills: Employment in 2030. Available at https://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~mosb/public/pdf/2864/Bakhshi%20et%20al.%20-%202017%20-%20The%20future%20of%20skills%20employment%20in%202030.pdf

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Artificial Intelligence Achieves Near-Human Performance in Diagnosing Breast Cancer. ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 20 June 2016.

Brynjolfsson E. & McAfee A. (2012). Race Against The Machine: How The Digital Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly Transforming Employment and The Economy. The MIT Center for Digital Business. Research Brief January 2012.

Dellermann, D.; Calma, A.; Lipusch, N.; Weber, T.; Weigel, S. & Ebel, P. (2019): The Future of Human-AI Collaboration: A Taxonomy of Design Knowledge for Hybrid Intelligence Systems. In: Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). Hawaii, USA.

Frey C. & Osborne M. (2013). The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation? Oxford Martin School Working Paper.

Goldin C & Katz LF (2009). The Race between Education and Technology: The Evolution of U.S. Educational Wage Differentials, NBER Working Paper No. 12984. Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/lkatz/publications/race-between-education-and-technology-evolution-us-educational-wage-differentials

Newton D. (2018). What Mark Twain Didn't Really Tell Us About Technology Disruption, Jobs And Education. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/dereknewton/2018/07/26/what-mark-twain-didnt-really-tell-us-about-technology-disruption-jobs-and-education/#17a9f6da42e2

Pew Research Center (2018). Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humans. Concerns About Human Agency, Evolution and Survival. Retrieved from https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/12/10/concerns-about-human-agency-evolution-and-survival/

Rao S.A. & Verweij G. (2017). Sizing the Prize: What’s the Real Value of AI for your Business and How can you Capitalise? PwC Report. Retrieved from https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/analytics/assets/pwc-ai-analysis-sizing-the-prize-report.pdf

The British Academy & The Royal Society (2019). The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Work: An Evidence Synthesis on Implications for Individuals, Communities, and Societies. Retrieved from https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/AI-and-work-evidence-synthesis.pdf

Top Rated

About the Author

Comments

Most Read Articles

Blog Categories

RELATED SERVICES

Add comment