- Blog

- Revamping hierarchy

Contents

- There is an academic and practical fascination with radical decentralization

- A hierarchical organization is characterized by different ranks of power and control

- Hierarchy is the oldest form of human organization

- Hierarchy creates a psychologically rewarding environment

- Hierarchy functions as an incentive system - the more success, the higher the status

- Hierarchies can be good or bad depending on organization and situation

- The less stable the environment, the less effective hierarchies can be

- Less hierarchical forms of organizing are gaining traction as the nature of work is changing

- Flatterning or delayering can help revamp the hierarchical states in organizations

- One common form of delayered hierarchies in organizations is team networks

- New organizational structures help supplement and consolidate familiar hierarchies

- References and further reading

People respond to hierarchies with strong emotional reactions: understandably so, as hierarchies determine so many aspects of their lives—from their standard of living, and the work opportunities they get, to their mental, emotional, and financial wellbeing. Depending on their own experiences and their individual position in the hierarchy, people tend to either approve them with enthusiasm or reject them with strong aversion - but they rarely, if ever, show ambivalence (Halevy, Chou, & Galinsky, 2011).

With the high-speed technological changes and the dramatic impact they have on the way we work, play, and everything in between, the idea of scraping hierarchies to the point of radical decentralisation started to attract attention, first within the practitioners’ community but then in academic circles as well. This blog post aims to explore whether a hierarchy is an obsolete concept and how to reinvent it to better fit the current environment characterized by increasing complexity and uncertainty.

There is an academic and practical fascination with radical decentralization

Fascination with organizations that shun the conventional hierarchy and evangelize the radical decentralization of authority, although not new, was at the margin of both academics' and practitioners' attention. However, recently, organizational experiments in radical decentralization have gained mainstream position. Still, academic understanding of radical decentralization remains limited.

Lee and Edmondson (2017) shed some academic light on the better understanding of less-hierarchical organizing at its limits. They use the term 'self-managing organizations' to describe those that radically decentralise authority in a formal and systematic way throughout the organization.

A hierarchical organization is characterized by different ranks of power and control

But before diving into the inner workings of a radically decentralized organization, I will take one step back and try to find answers to the following questions:

- Are hierarchies in organizational setting really that obsolete?

- Can we avoid the polarisation and take a mix-and-match approach between hierarchical and decentralized systems?

- Can taking the best bits from both systems and creating a solution on the spectrum between the two extremes be beneficial?

Hierarchy is an organization based on establishing, maintaining, and (usually) formalising differences among members of an organization. This differentiation translates into ranking of power, control, independence, resource allocation, and respect (Blau & Scott, 1962). Hierarchies can vary considerably in the degree of formalisation (Gruenfeld & Tiendes, 2010).

Hierarchy is the oldest form of human organization

Thinking about hierarchy in historical context, we will inevitably find that the concept has existed since humans started living in organised formations, which, considering that we are social animals, is basically since ever. We naturally tended towards hierarchy long before we spent any time contemplating the most efficient and effective way to organise ourselves as we do nowdays.

Halevy, Chou, and Galinsky (2011) explore the reasons behind the fact that hierarchy is the oldest and most widespread form of human organization. They propose five ways in which hierarchy can enhance performance: there is evidence that hierarchies better satisfy certain basic psychological needs, such as the need for power and achievement, the need for certainty, predictability, and structure rather than egalitarian social modalities (Gruenfeld & Tiendes, 2010).

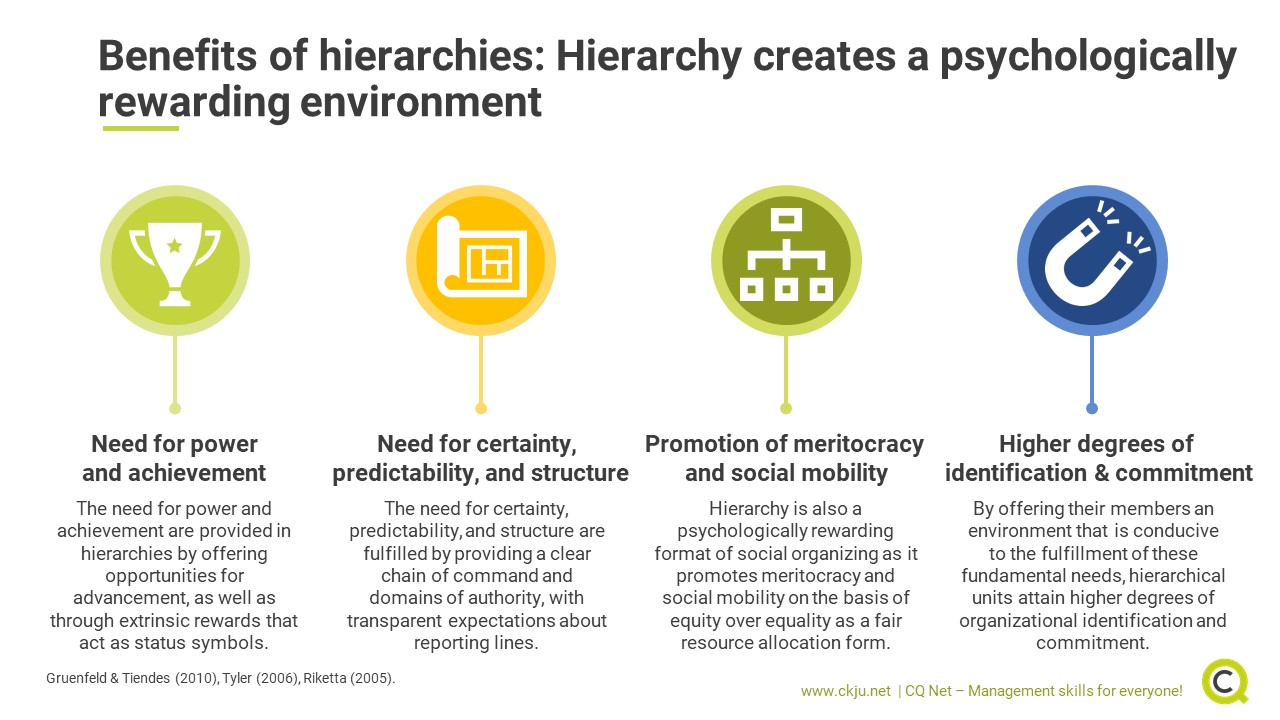

Hierarchy creates a psychologically rewarding environment

It is not without reason that one of the oldest form of organizing relies on hierachies. Before we start looking at strategies to get rid of them we'll briefly explore the benefits of a hierarchical organizational.

Need for power and achievement

The need for power and achievement are provided in hierarchies by offering opportunities for advancement, as well as through extrinsic rewards that act as status symbols.

Need for certainty, predictability, and structure

The need for certainty, predictability, and structure are fulfilled by providing a clear chain of command and domains of authority, with transparent expectations about reporting lines.

Promotion of meritocracy and social mobility

Hierarchy is also a psychologically rewarding format of social organising as it promotes meritocracy and social mobility on the basis of equity over equality as a fair resource allocation form. This is essential as perceptions of social and organizational justice infuse legitimacy into the system, which promotes respect and cooperation (Tyler, 2006).

Higher degrees of organizational identification and commitment

By offering their members an environment that is conducive to the fulfillment of these fundamental needs, hierarchical units attain higher degrees of organizational identification and commitment, which in turn enhances performance (Riketta, 2005).

Hierarchy functions as an incentive system - the more success, the higher the status

There is a considerable body of research that suggests that hierarchy improves performance because it provides an effective incentive system (Magee & Galinsky, 2008; Ridgeway, 1987) through the use of promotion, differential pay, and various status symbols such as office size, job title, and parking location to visibly reward certain individuals (Gruenfeld & Tiedens, 2010).

Interestingly, these findings hold true both for high- and low-ranked group members. After being rewarded with a higher position, higher-ranked members respond by increasing their effort, which allows them to not only maintain their high rank but to serve organizational goals at the same time (Gould, 2002).

Lower ranked members are motivated to increase their effort for four reasons:

- to decrease the likelihood of immediate sanctions and increase the likelihood of immediate rewards;

- because it leads to long-term promotional opportunities;

- because there is evidence that low-ranked members take pleasure in positive interactions with high-rank members (Gould, 2002);

- to increase their efforts to achieve these rewards themselves (Magee & Galinsky, 2008).

Hierarchies can be good or bad depending on organization and situation

Notwithstanding the evident benefits that hierarchy brings, there are certain environments where this impact is particularly strong. Halevy, Chou, and Galinsky (2011) suggest that hierarchical form of organization is especially beneficial:

- For organizations where there is a higher degree of task interdependence, because task interdependence is a force that creates the need for hierarchy. Hierarchy can enhance performance through its psychological effects on the group-level processes that were identified previously.

- Hierarchy is more likely to have a positive effects on performance when it has high rather than low legitimacy.

- Hierarchy is more likely to facilitate group functioning and performance when different dimensions of hierarchy such as competence, dominance, power, prestige are aligned rather than misaligned. Misalignment of different dimensions of the hierarchy will decrease its ability to satisfy the basic human needs for structure and predictability and will fail to motivate performance through hierarchy-related incentives effectively.

The less stable the environment, the less effective hierarchies can be

However, over the last fifty years, a tendency of managerial hierarchy (whereby the flow of directives runs from top to bottom) to become rigid has become increasingly evident. Indeed, research suggests that managerial hierarchy functions more effectively in stable conditions but faces serious challenges in dynamic conditions (Burns, 1961; Mintzberg, 1979). It also enables efficient execution of known tasks but hinders complex non-routine task execution, especially those that span across functional boundaries (Adler, 2001; Barley, 1996; Heckscher & Donnellon, 1994).

Less hierarchical forms of organizing are gaining traction as the nature of work is changing

First, the pace of the change due to technological developments are not compatible with rigid managerial hierarchy. Then, there is a significant growth in knowledge-based work - the whole economy is becoming increasingly knowledge-based, as ideas and competence comprise the dominant sources of value creation (Blacker, Reed & Whitaker, 1993). Finally, improving employee experiences is gaining both academics' and practitioners' attention, as work and organizations are viewed more and more as sources of personal meaning since some traditional sources of meaning play a declining role in many parts of society.

These shortcomings have sparked both academics' and practitioners' interest to search for less-hierarchical forms of organizing. As there is still a widespread view that hierarchical organizing is both lasting and natural (Gruenfeld & Tiedens, 2010), understanding whether and how organizations can deviate from the managerial hierarchy in practice, not just in theory, is essential.

Flatterning or delayering can help revamp the hierarchical states in organizations

There has been an ongoing trend of flattening or delayering in the corporate sector. Rajan & Wulf (2006) conducted a panel analysis of over 300 large U.S. firms tracked over a period of up to 14 years. They find that

- companies are becoming flatter,

- the CEO span is becoming broader,

- intermediate managers are being dispensed with, and

- divisional managers are getting more authority, higher pay, and are becoming closer to the CEO.

Although companies are getting flatter, it cannot be simply characterized as centralization or decentralization. Centralization is present as the CEO is getting more involved with lower levels of the organization, but decision-making and incentives are pushed down, too, and that is a form of decentralization.

Despite the fact that organizations have fewer management layers than ever before, there is little evidence on how this should be achieved. Kettley (1995) identifies three methods:

- delayering as downsizing,

- delayering as part of cultural change,

- and delayering of pay grades.

One common form of delayered hierarchies in organizations is team networks

One of the most common forms of delayered or flattened organization is the so-called 'network of teams', which characterized by a high degree of empowerment, strong communication, and fast information flow. Authority is decentralized to highly trained and empowered teams with real-time, accurate data about activities.

Unlike traditional hierarchically structured organizations where management sets goals and tells people what to do, in the new model, goals are set at the bottom, and managers are not evaluated by the span of control, but by performance while performance management is a continuous process. However, a formal structure is still needed to ensure that the network of teams works effectively (McDowell et al., 2016).

The principles of the network of team organizational forms are (McDowell et al., 2016).:

- People are grouped in customer-, product-, or market- and mission-focused teams that are led not by professional managers, but by leaders who are experts in their domain.

- Teams have the freedom to set their own goals and make their own decisions within the given strategy or business plan.

- There is information and operations center to gather and share information and identify links between team activities and desired results.

- Teams are not organised around business function, but around the mission, product, market, or integrated customer needs.

- People are encouraged to work across teams and enabled to move from team to team as needed.

- Senior leaders are in roles that are focused on planning, strategy, vision, culture, and cross-team communication.

New organizational structures help supplement and consolidate familiar hierarchies

The new structures are based on the ability of a company to quickly design, deploy, dissolve, and reform teams. But these new models do not mean that functional organizations are going away, but that they are being supplemented by so-called service centers and centers of excellence to enable scale and consolidate administrative activities (McDowell et al., 2016).

References and further reading

Adler, P. S. (2001). Market, hierarchy, and trust: The knowledge economy and the future of capitalism. Organization science, 12(2), 215-234.

Barley, S. R. (1996). Technicians in the workplace: Ethnographic evidence for bringing work into organizational studies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 404-441.

Blacker, F., Reed, M., & Whitaker, A. (1993). Editorial introduction: knowledge workers in contemporary organisations. Journal of Management Studies, 30(6), 851-862.

Burns Т, S. G. (1961). The management of Innovation. L.: Tavistock.

Gould, R. V. (2002). The origins of status hierarchies: A formal theory and empirical test. American journal of sociology, 107(5), 1143-1178.

Gruenfeld, D. H., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2010). Organizational preferences and their consequences. Handbook of social psychology, 2, 1252-1287.

Halevy, N., Y. Chou, E., & D. Galinsky, A. (2011). A functional model of hierarchy: Why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance. Organizational Psychology Review, 1(1), 32-52.

Heckscher, C., & Donnellon, A. (Eds.). (1994). The post-bureaucratic organization: New perspectives on organizational change. SAGE Publications, Incorporated.

Kettley, P., & Thompson, M. (1995). Is Flatter Better. De-layering the Management Hierarchy', IES Report, 290, 1995.

Lee, M. Y., & Edmondson, A. C. (2017). Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Research in organizational behavior, 37, 35-58.

Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). 8 social hierarchy: The self‐reinforcing nature of power and status. Academy of Management annals, 2(1), 351-398.

McDowell T, Miller D., Agarwal D., Okamoto T., and Page T. (2016). Organizational design: The rise of teams. Deloitte University Press. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/human-capital-trends-introduction/DUP_GlobalHumanCapitalTrends_2016_4.pdf

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of Organizations, Pearson.

Rajan, R. G., & Wulf, J. (2006). The flattening firm: Evidence from panel data on the changing nature of corporate hierarchies. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 759-773.

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis. Journal of vocational behavior, 66(2), 358-384.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 57, 375-400.

Top Rated

About the Author

Comments

Most Read Articles

Blog Categories

RELATED SERVICES

Add comment