- All Management Learning Resources

- Decisiveness

Why should you care about decisiveness?

As a professional it is your daily business to make decisions. This applies to your professional life in the same way as to your private life. Moreover, with an increased focus on self-responsibility, most organizations expect from their employees to be decisive. Consequently, decisiveness is a key characteristic important for professionals in leadership positions and beyond. We have a look at the foundation of decisiveness, how it works and what you can do to benefit from it.

Contents

- Why should you care about decisiveness?

- What is decisiveness?

- How does decisiveness work?

- How to measure decisiveness?

- How to implement decisiveness?

- What are the benefits of decisiveness?

- Critical appraisal of decisiveness: Solidity Rating 3

- Key recommendation for professionals

- References and further reading

What is decisiveness?

In a fast-paced environment it is key to make timely decisions without losing time. Decisiveness is basically a trait or characteristic that describes people who are biased towards action even though they face uncertainty (Simpson et al., 2002). This makes decisiveness an important concept for professionals in almost any domain.

In politics, decisiveness or the perception whether one is decisive or not can make the difference whether presidential candidates win an election or not (Bernheim and Bodoh-Creed, 2020). In other areas such as healthcare and the private sector, decisiveness is perceived as a strength and success factor (Halstead, 1989).

In management it makes most sense to think of decisiveness as personality trait (Barrick and Zimmerman, 2005) which can be measured and developed to a certain extent. You should also consider that decisiveness is not necessarily connected to decision-making quality. In other words, decisive action can do more harm than good when the decision was the wrong one. The concept of decision-making competence (DMC) provides guidance how to improve decision-making quality.

How does decisiveness work?

In order to better understand the concept of decisiveness, it is important to know how it works. From a management skills point of view, we decided to have a detailed look at the following three ways to understand how decisiveness works:

- Decisiveness as a personality trait

- Decisiveness and cultural differences

- Decisiveness and decision-making competence

Decisiveness as a personality trait

On a basic level, you can understand decisiveness as a personality trait. From this perspective, decisiveness is an enduring and stable characteristic that describes how people behave in similar decision-making situations. There are various personality models you can use to explain how decisiveness works.

For instance, Chapman et al. (2013) found that decisiveness is part of the extraversion personality dimension in one of the early Eyseneck personality models. The associated question “Do you like doing things in which you have to act quickly” (Chapman et al., 2013) emphasizes the speed and determination of decisiveness as personality trait. In a more recent personality model, the Five Factor model of personality (also known as the Big 5 model), decisiveness is more closely connected to the personality traits of consciousness (Barrick and Zimmerman, 2005).

In this Big 5 model, conscientiousness consists of the personality subdomains order, self-discipline and achievement striving which one could argue point into a similar direction as decisiveness. However, there is no clear-cut answer available yet whether it is fully covered by the personality domain consciousness or whether it is also related to other domains in the big 5 model.

Decisiveness in feminine and masculine cultures

Cultural differences are another approach to understand how decisiveness works. In a study about intercultural differences, Hofstede (1996) found that decisiveness is a cultural attribute more closely connected to masculinity. Organizations and countries that tend towards a culture of masculinity lean towards influencing strategies that rely on authority, power, control and decisiveness (Shapiro et al., 2011).

This also explains why decisiveness plays a prominent role in traditional leadership approaches such as the great man theory. Therefore, especially in masculine cultures decisiveness is a characteristic people expect from leaders and professionals as basis to perform well (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005).

Decisiveness and decision-making competence

Being decisiveness does not necessarily mean that one makes the right decisions. In some high-risk cases, making the wrong decision could lead to a worse outcome compared to making no decision at all. Therefore, it is important not just to be decisive but to work on your decision-making competence.

According to Parker and Fischhoff (2005) decision-making competence consists of the following seven categories:

- Consistency in risk perception

- Recognizing social norms

- Resistance to sunk costs

- Resistance to framing

- Applying decision rules

- Path independence

- Under/overconfidence

How to measure decisiveness?

Decisiveness can be measured and observed. For instance, there are personality test such as the NEO-PI which relies on the above mentioned five factor model of personality. Taking a personality test can help you to get a better understanding whether decisiveness is part of your personality profile.

Another way to measure whether you are biased towards action is to use one of the available indecisiveness scales. Germeijs and Boeck (2002) developed such a questionnaire that contains 22 items and has good psychometric properties. It covers questions such as “I find it easy to make decision” and “I don't know how to make a decision” (Germeijs and Boeck, 2002).

Finally, you can spend some time for self-reflection of recent situations where you had to make an important decision. In addition, you can also ask people close to you how they experience you when it comes to timely decisions and bias towards action.

How to implement decisiveness?

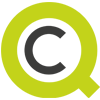

There are several ways to implement and strengthen your bias towards action. We will have a look at four interventions with a proven track record of having a positive impact on decisiveness and whether people experience you as a decisive professional.

Know your personality and your decision-making style

The first intervention is about knowing your personality strengths and weaknesses as well as your decision-making style. Once you better understand how you behave in different decision-making situations, you can start to work on your strong and weak points. Keep in mind that changing one’s traits is nothing which will happen overnight. An experiences management counselor can provide you the necessary support to develop to the next level.

Build and maintain healthy social relationships

Social relationships are an important part of our professional and private life. Having strong and healthy social relationships helps to boost self-esteem which is an important driver of decisiveness (Harris and Orth, 2020). In addition, asking others for their opinion regarding important decisions can help you to think out of the box and improve decision-making quality.

Foster transparency in decision-making

Decisiveness alone is not sufficient to be seen as decisive by people around you. Others need to experience you as somebody who makes timely decisions and moves things forward. Foster transparency in your decision-making and decision-implementation process. Inform key stakeholders about important decisions taken and how your efforts towards implementation progress.

Use management tools with a regular decision-making cycle

Another way to implement decisiveness is to rely on management tools that have an build-in decision-making requirement. For instance, agile approaches such as SCRUM, Kanban and agility in general require you to go through a regular decision-making cycle.

What are the benefits of decisiveness?

As a professional it is important to know the benefits associated with decisiveness. Most organizations expect that professionals make timely decisions and have a focus on implementation. Being decisive is thus a trait generally considered as a strength.

On a more specific level, there are some research findings that support the claim that decisiveness is connected to a set of positive work outcomes. In a study of governmental executives Kelman et al. (2017) found that high-performing manager were more biased toward action than the comparison group. Decisive managers seem also to reduce the risk of experiencing stress in their employees (Mulki et al., 2012).

Critical appraisal of decisiveness: Solidity Rating 3

Based on the available evidence that supports the positive effects associated with decisiveness, this CQ Dossier is assigned a Level 3 rating (Based on a 1- 5 measurement scale). This rating reflects the lack of rigorous empirical studies and the ambivalence of the concept of decisiveness as management tool. However, the available knowledge about decisiveness and how to implement it sufficient to utilize it as management tool in practice.

Key recommendation for professionals

- Decisiveness is a characteristic that describes people who are biased towards action

- It can be explained as a personality trait, a cultural attribute connected to masculinity and implicit expectations about leaders and leadership

- Decisiveness is different to decision-making competence. High-quality decisions require both decisiveness and decision-making competence

- There are tools such as personality tests available that help you to work on your bias towards action

- Fostering healthy social relationships and transparent decision-making helps you to strengthen your decisiveness

- Decive action is related to a set of positive outcomes such as performance

- However, there is need for more research to better understand the relationship between performance and decisiveness

References and further reading

Barrick, M. R. and Zimmerman, R. D. (2005) ‘Reducing voluntary, avoidable turnover through selection’, The Journal of applied psychology, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 159–166.

Bernheim, B. D. and Bodoh-Creed, A. L. (2020) ‘A theory of decisive leadership’, Games and Economic Behavior, vol. 121, pp. 146–168.

Chapman, B. P., Weiss, A., Barrett, P. and Duberstein, P. (2013) ‘Hierarchical Structure of the Eysenck Personality Inventory in a Large Population Sample: Goldberg's Trait-Tier Mapping Procedure’, Personality and individual differences, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 479–484.

Germeijs, V. and Boeck, P. de (2002) ‘A Measurement Scale for Indecisiveness and its Relationship to Career Indecision and Other Types of Indecision’, European Journal of Psychological Assessment, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 113–122.

Halstead, F. A. (1989) ‘Boards want leadership and decisiveness’, Physician executive, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 12–14.

Harris, M. A. and Orth, U. (2020) ‘The link between self-esteem and social relationships: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies’, Journal of personality and social psychology, vol. 119, no. 6, pp. 1459–1477.

Hofstede, G. (1996) ‘Gender Stereotypes and Partner Preferences of Asian Women in Masculine and Feminine Cultures’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 533–546.

Hogan, R. and Kaiser, R. B. (2005) ‘What we know about Leadership’, Review of General Psychology, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 169–180.

Kelman, S., Sanders, R. and Pandit, G. (2017) ‘“Tell It Like It Is”: Decision Making, Groupthink, and Decisiveness among U.S. Federal Subcabinet Executives’, Governance, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 245–261.

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, F., Malhotra, S. and Locander, W. B. (2012) ‘Reluctant employees and felt stress: The moderating impact of manager decisiveness’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 77–83.

Parker, A. M. and Fischhoff, B. (2005) ‘Decision-making competence: External validation through an individual-differences approach’, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–27.

Shapiro, M., Ingols, C. and Blake-Beard, S. (2011) ‘Using Power to Influence Outcomes’, Journal of Management Education, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 713–748.

Simpson, P. F., French, R. and Harvey, C. E. (2002) ‘Leadership and negative capability’, Human Relations, vol. 55, no. 10, pp. 1209–1226.

About the Author