- All Management Learning Resources

- High-performance work practices

Executive summary

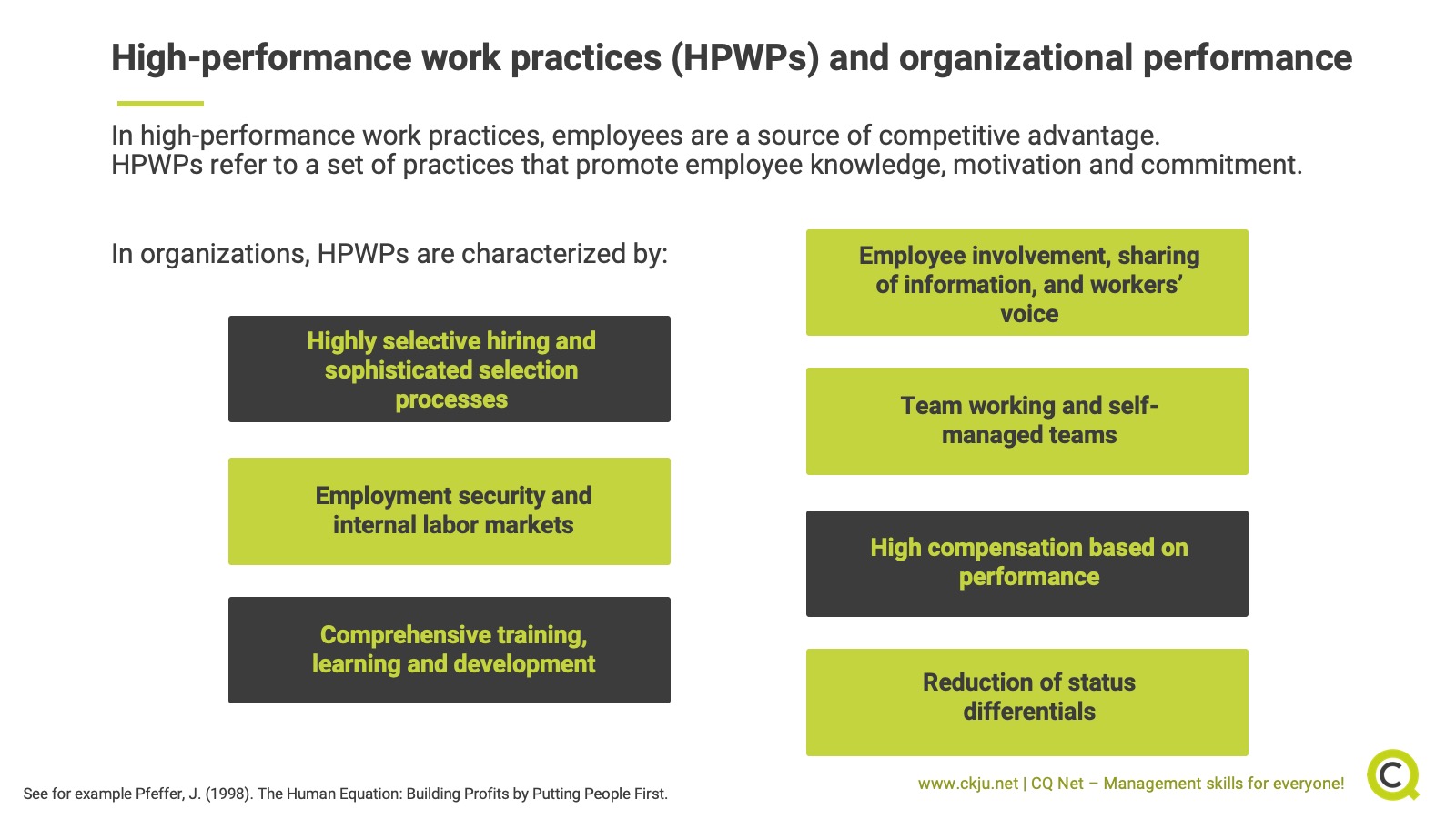

High-performance work practices are defined as a way of organizing work in which employees participate in making decisions that have a real impact on their jobs and the broader organization. The aim of these practices is to achieve a high-performance culture, one in which the norms, values, and human resources are combined to create an environment in which the achievement of high levels of performance is a way of life. This CQ Dossier describes the merits and shortcomings of high-performance work practices (HPWPs), explains why they matter, and gives recommendations on how they can be implemented in practice.

Contents

- Executive summary

- What are high-performance work practices?

- High-performance work practices are a set of coherent and consistent practices that see people as a source of competitive advantage

- High-performance work practices empower employees, which helps organizational efficiency and performance

- HPWPs are not based on control but on employee autonomy, decision-making and responsibility

- Why do high-performance work practices matter?

- A high-performance workforce is a source of untapped potential for many organizations

- What is the relationship between HPWP and organizational performance?

- What are the benefits of high-performance work practices?

- What are shortcomings of high-performance work practices?

- How can high-performance work practices be implemented?

- Organizations must motivate employees to leverage their knowledge, skills and abilities

- Key Take-Aways

- References and further reading

What are high-performance work practices?

The strategic importance of human resource management and its impact on financial performance has created substantial interest within academic and practitioner communities. This interest is focused on the potential of high-performance work practices (HPWPs) to act as a unique, sustainable resource supporting the implementation of corporate strategy and the achievement of operational goals.

The terms such as knowledge workers, intellectual capital, and high-performance work systems reflect a new interest in people as a source of competitive advantage rather than as a cost that needs to be minimized. Consequently, people as intellectual assets and the systems within an organization designed to attract, develop, and retain them are emerging as significant elements of the strategic decision-making process (Becker & Huselid, 1998).

High-performance work practices are a set of coherent and consistent practices that see people as a source of competitive advantage

Although HPWPs have neither been consistently defined nor uniformly named, Datta et al. (2005) point out that HPWPs are most commonly viewed as a set of internally coherent and consistent human resources practices designed to

- promote employee knowledge,

- motivation, and

- commitment.

Also called “high-performance work systems or alternate/flexible work practices” (Delaney & Godard, 2001), these programs share some common elements including rigorous recruitment and selection processes, performance-based incentives, and comprehensive training programs centered around the needs of the business (Becker, Huselid, Pickhus, & Spratt, 1997).

High-performance work practices empower employees, which helps organizational efficiency and performance

HPWPs involve substantial investment in human capital to empower employees by developing their knowledge, skills, flexibility, and motivation, with the expectation that the employer will provide them with the ability and the opportunity to deliver input into workplace decisions (Van Buren & Werner, 1996).

In return, companies expect that empowered employees will be able to adapt quickly to rapidly changing market conditions, thus improving operational efficiency and performance of the company (Becker & Huselid, 1998; Cappelli & Neumark, 1999).

Pfeffer (1998) outlines the main components of HPWPs in organizations:

- Highly selective hiring and sophisticated selection process

- Employment security and internal labour markets

- Comprehensive training, learning, and development

- Employee involvement, sharing of information, and workers’ voice

- Team working/Self-managed teams

- High compensation based on performance

- Reduction of status differentials

Management skills newsletter

Join our monthly newsletter to receive management tips, tricks and insights directly into your inbox!

HPWPs are not based on control but on employee autonomy, decision-making and responsibility

HPWPs are intended to lead to a highly motivated, skilled, and empowered workforce, with the goals of the employees closely aligned with those of the management (Flood, MacCurtain & Guthrie, 2005).

They are part of so-called “high involvement work practices”, or those in which managers seek to involve the employees in decision making and encourage them to exercise discretion, making them more responsible. In contrast, control-oriented work processes are those in which managers try to control decisions.

Why do high-performance work practices matter?

Huselid (1995) reports that companies using HPWPs benefit from reduced employee turnover while increasing their productivity and financial performance. Becker and Gerhart (1996) also indicate that HPWPs can act as a source of competitive advantage as long as the managerial practices are aligned with existing organizational features (internal fit) and with strategic and operating objectives (external fit).

HPWPs need the support and trust of employees to be effective

The prerequisite for HPWPs to have a positive impact on organizational performance is that employees view the associated practices as positive. Appelbaum et al., (2000) cite that trust and intrinsic rewards (i.e., motivating employees to use their skills), organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and work-related stress are outcomes that are not necessarily in the interests of the company to the same extent that they are to the employee.

A high-performance workforce is a source of untapped potential for many organizations

The strategic importance of human resource management in which the skilled and motivated workforce provides the speed and flexibility essential in the challenging business environment is increasingly acknowledged, especially as traditional sources of competitive advantage (technology, quality, economies of scale, etc.) have grown easier to imitate. As the markets for other sources of competitive advantage are becoming ever more efficient, the intricacies around the development of a high-performance workforce remain a considerable unrealized opportunity for many organizations (Becker & Huselid, 1998).

What is the relationship between HPWP and organizational performance?

Although there exists increasing evidence that HPWPs affect organizational performance, the magnitude of the overall effect remains difficult to estimate due to differences in research designs, performance measures, sample characteristics, and methodologies of the existing studies, which resulted in their findings to vary dramatically.

Combs et al. (2006) conducted a meta-analysis of 92 studies to estimate the size of this effect and to test whether effects are larger for

- HPWP systems versus individual practices,

- operational versus financial performance measures, and

- manufacturing versus service organizations.

Research on HPWPs is highly relevant for questions relating to the dynamic world of work today

The meta-analysis reveals an overall correlation estimated at 0.2, with a stronger relationship in the case of HPWP systems and among manufacturers. The relationship appears invariant across performance measures (financial vs. operational). The authors use their findings to offer suggestions for future research that might answer today’s emerging questions.

This research offers five contributions:

- It statistically aggregates existing evidence on the impact of HPWPs on organizational performance, providing a conservative point estimate of the relationship’s strength.

- It tests a central claim of strategic human resources management theory - the claim that HPWPs reinforce and boost each other when used in harmonized systems of HPWPs (Huselid, 1995).

- It explores whether the relationship varies depending on the distance between performance measures and employees’ daily work (i.e., operational measures vs. financial measures).

- It tests whether HPWPs are more impactful in manufacturing than in services settings.

- It offers suggestions for future research to ensure that today’s emerging questions are addressed in the future.

Organizational systems are holistic entities - HPWPs must be implemented in a holistic manner

HPWPs, when implemented correctly, improve productivity and quality, but the key is to view systems not component by component, but in a holistic manner - how they can be implemented in an all-embracing way. This approach involves implementation around the firm as a whole, including technology, employees, and their workplaces (Aghazadeh & Seyedian, 2004).

What are the benefits of high-performance work practices?

Combs et al. (2006) argue that HPWPs improve organizational performance through three interconnected processes:

- They give employees the KSAs (knowledge, skills, and abilities) necessary to perform their tasks and the motivation and opportunity to do so (Delery & Shaw, 2001).

- They improve the social structure within organizations, which enables effective communication and collaboration among employees (Evans & Davis, 2005).

- Jointly, these two processes improve job satisfaction and ensure more productive work, which, in turn, reduces employee turnover (Becker et al., 1997).

HPWPs are correlated with productivity and safety indicators

Tregaskis et al. (2013) conducted a longitudinal case study to explore the causal relationship between HPWPs and performance using a quasi-experimental design in a single case. The research draws on longitudinal data from managers, employees and unions gathered during the implementation of HPWP interventions over 30 months, in combination with performance metrics collected before and after the HPWP interventions (over 66 months).

These data are used to evaluate the effects of the introduction of HPWP interventions on performance over time. Analysis of the performance data revealed that the introduction of HPWPs had a sustained impact on productivity and safety indicators, but the effect is delayed from one quarter to two quarters, respectively.

HPWPs help employees express their ideas on the functioning of an organization

Chamberlin, Newton & LePine (2018) conducted a meta‐analysis of 151 independent samples involving 53.200 employees to explore empowerment and voice as transmitters of high‐performance managerial practices to job performance. Voice is viewed as the discretionary expression of employees’ constructive ideas regarding the functioning of an organization.

Although empowerment offers the predominant explanation of the positive relationship between high‐performance managerial practices and employee job performance, the authors propose that these practices also affect performance as they support employees to engage in voice.

The authors also suggest that empowerment and voice combined provide a complete explanation of the link between HPWPs and job performance, as empowerment transmits the positive effects because it engenders voice. The authors find in particular the positive effects of opportunity‐enhancing practices, because employees respond to opportunity enhancing practices with voice.

What are shortcomings of high-performance work practices?

Although HPWP practices are generally considered to have a positive impact on employees’ wellbeing, there also exist certain opposing views. Judith Mair, in her widely-discussed, albeit controversial book “End of Fun," claims that conventional work systems provide a more beneficial work environment and also result in better organizational performance.

Flat hierarchy, flexibility and agility, self-actualization, and the like supersede conventional organizational forms, but with destructive consequences: employees are slowly becoming disorientated due to decentralized decision-making; they don’t know what is expected from them as responsibility is passed on from one team member to another.

Critics see HPWPs as too unconventional, being disorienting and blurring the boundaries between private life and work life

Mair states that work has to be work - nothing more and nothing less; she argues that it is more important to ensure that employees are satisfied than to promise fun at work or to present the workplace as a new home and status. Instead, a well-defined structure with elements such as system of rules, discipline, performance orientation, and obligatory modes of communication is needed to provide basic security for workers to feel comfortable. Mair supports selective access to information, precise instructions, clear responsibilities, less focus on soft skills, and a realistic corporate culture. (Mair, 2003).

How can high-performance work practices be implemented?

HPWPs improve organizational performance by increasing employees' knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs), empowering them to utilize their KSAs for the organizational benefit, and motivating them to do so. KSAs are introduced and ensured by adequate recruiting and selectivity (Hoque, 1999) and then further advanced through practices such as training, adequate job design, and compensation linked to skill development (Hoque, 1999; Russell, Terborg, & Powers, 1985).

Organizations must motivate employees to leverage their knowledge, skills and abilities

Employees have the possibility to perform below their true potential as they possess discretionary power over the use of their time and talent. For this reason, organizations need to find a way to motivate employees to leverage their KSAs (Bailey, 1993). Organizations often utilize tools such as internal promotion policies, performance appraisal, incentive compensation, flexible work schedules, employment security, and procedures for airing grievances to motivate their employees.

However, even skilled, knowledgeable, and motivated employees will not employ their discretionary time and talent unless the organizational and job designs offer the freedom to act (Bailey, 1993; Huselid, 1995). This freedom can be provided by HPWPs such as self-managed teams, participation programs, information sharing, and employment security (Delery & Shaw, 2001; Pfeffer, 1998).

Key Take-Aways

- HPWPs improve organizational performance by increasing employees' knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs).

- Three broad concepts underpin HPWPs:

- An inclusive and people-centered, open and creative culture, where decision-making is clearly communicated and shared throughout the organization.

- Investment in people through training, education, flexible working, loyalty, and inclusiveness.

- Measurable performance outcomes such as setting targets and benchmarking, as well as innovation through processes and best practice.

References and further reading

Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P., Kalleberg, A. L., & Bailey, T. A. (2000). Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off. Cornell University Press.

Becker, B., & Gerhart, B. (1996). The impact of human resource management on organizational performance: Progress and prospects. Academy of management journal, 39(4), 779-801.

Becker, Brian & Huselid, Mark & Pickus, Peter & Spratt, Michael & P, Coopers. (1998). HR as a Source of Shareholder Value: Research and Recommendations. Human Resource Management. 36. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199721)36:13.0.CO;2-X.

Becker, E. & Huselid, Mark. (1998). High performance work systems and firm performance: A synthesis of research and managerial implications. Research in Personnel and Human Resource Management. 16. 53-101.

Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Flood, P., Liu, W., MacCurtain, S., & Guthrie, J. P. (2005). High performance work systems in Ireland-The economic case.

Cappelli, P., & Neumark, D. (2001). Do “high-performance” work practices improve establishment-level outcomes?. ILR Review, 54(4), 737-775.

Chamberlin, Melissa & Newton, Daniel & LePine, Jeffery. (2018). A meta-analysis of empowerment and voice as transmitters of high-performance managerial practices to job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 39. 10.1002/job.2295.

Combs, James & Liu, Yongmei & HALL, ANGELA & KETCHEN, DAVID. (2006). How Much Do High-Performance Work Practices Matter? A Meta-Analysis of Their Effects on Organizational Performance. Personnel Psychology - PERS PSYCHOL. 59. 501-528. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00045.x.

Datta, D. K., Guthrie, J. P., and Wright, P. M. (2005). Human resource management and labor productivity: does industry matter? Acad. Manage. J. 48, 135–145. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2005.15993158

Delaney, John & Goddard, John. (2001). An IR perspective on the high-performance paradigm. Human Resource Management Review. 11. 395-429. 10.1016/S1053-4822(01)00047-X.

Delery, J. E., & Shaw, J. D. (2001). The strategic management of people in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and extension. In Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 165-197). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Evans, W. R., & Davis, W. D. (2005). High-performance work systems and organizational performance: The mediating role of internal social structure. Journal of management, 31(5), 758-775.

Hoque, K. (1999). Human resource management and performance in the UK hotel industry. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 37(3), 419-443.

Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of management journal, 38(3), 635-672.

Mair, Judith 2003. Schluss mit lustig. Warum Leistung und Disziplin mehr bringen als emotionale Intelligenz, Teamgeist und Soft Skills. Frankfurt am Main: Eichborn AG.

Mirzamani, Seyed-Mahmoud & Seyedian, Mojtaba. (2004). The high-performance work system: is it worth using?. Team Performance Management. 10. 60-64. 10.1108/13527590410545054.

Pfeffer, J. (1998). The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First.

Tregaskis, Olga & Daniels, Kevin & Butler, Peter & Meyer, Michael. (2013). High Performance Work Practices and Firm Performance: A Longitudinal Case Study. British Journal of Management. 24. 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2011.00800.x.

Van Buren, M.E. & Werner, J.M. (1996). High performance work systems. Business and Economic Review, 43(1), 15–35.

About the Author