- All Management Learning Resources

- Organisational learning

Executive summary

To remain relevant in a VUCA environment characterized by rapid change and rising uncertainty, the ability to learn is critical - both for organisations and individuals. The field of organisational learning has emerged as essential in this highly demanding environment. Yet, it is still rife with elusiveness as there is little agreement on what organisational learning means and even less on how to develop a learning organisation. There is a tension between its rhetorical appeal of the concept, on one side, and the difficulties with operationalizing it on the other – a contrast that results in challenges when professionals and managers need to start putting organisational learning into practice. This CQ Dossier will aim to shed evidence-based light on organisational learning, giving practical insights on how to foster organisational learning in practice.

Contents

- Executive summary

- What is organisational learning?

- Organisational learning capability and how to measure it: The Organisational Learning Survey

- What are the benefits of organisational learning?

- How to foster organisational learning?

- How to improve organizational learning in practice

- Leaders are pivotal in fostering a learning environment

- Critical appraisal of organisational learning: Solidity Level 3

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

What is organisational learning?

Organisational learning as a discipline is the study of the learning processes of and within organisations (Karatas-Özkan & Murphy, 2010). During the past 30 years, since the ‘60s when Cyert and March (1963) first introduced the term, and especially during the past two decades, organisational learning has emerged as a fundamental concept in organisational theory and a critical subject for organisations, managers and professionals (Friedman, Lipshitz & Popper, 2005). Yet, despite exponential growth in the literature, organisational learning remains an elusive concept for both researchers and practitioners. Little agreement on what organisational learning is, leads to the lack of evidence-based guidelines for managers and professionals wishing to implement it.

Senge’s vision (1990), although uplifting and captivating, projected an irresistible image of the desired state—the learning organisation—while leaving vague the steps that managers and professionals need to take to achieve it. As a result, practitioners often find themselves inspired but at the same time unclear how they should proceed towards the implementation of these processes within everyday organisational contexts, especially in established organisations.

The concept of organizational learning is rather vague

It is no easy task to navigate the field. Friedman, Lipshitz, and Popper (2005) argue that there is a mystification of the concept to which both academic and popular literature contributed by:

- Continually providing new definitions, in part because the field attracted academics from a wide range of disciplines, from psychology, sociology, anthropology, and history to economics, management, and political science – each bringing their own perspective on the same subject.

- Anthropomorphizing organisational learning, or treating organisations as if they were human beings and applying models of individual learning to the organisational level.

- Splitting the field between visionaries and skeptics. For example, when Senge, whose book The Fifth Discipline (1990) contributed most to the subsequent proliferation of the subject in the ‘90s, held keynote speech at the annual conference of the Strategic Management Society in 1992, an informal poll of participants found that most academics thought that his address was mere “preaching,” while managers and consultants “loved it” (Friedman, Lipshitz, & Overmeer, 2001).

- The reification of terminology as the terms like double-loop learning, systems thinking, organisational memory, mental models, knowledge creation, competency traps, defensive routines, and absorptive capacity, have come into extensive use without necessarily articulating clear meanings or reflecting a significant change in practice.

- Active mystification as it appears that obscurity of the meaning and practical application of these concepts may actually increase its appeal.

Organizational learning frameworks provide guidance on how to implement it

A meta-analysis (Bapuji & Crossan, 2004) reviewed the literature published during the period 1990–2002, examining the prominent questions arising in the field, such as:

- What is learning and how is it different from constructs like 'change' and 'adaptation'?

- Who or what does the learning – an individual or an organisation?

- Is learning exogenous or endogenous?

The analysis revealed that there is a growing consensus in the literature that learning can be behavioral and cognitive, exogenous and endogenous, incremental and radical, and can occur at various levels in an organisation. The study is useful for evidence-based implementation of organisational learning, as it provides a systemized framework emerging from the consensus in academia on concepts such as:

- external (congenital, vicarious, and Inter-organisational Learning) and

- internal learning (from organisation's own cumulative experience),

- learning perspective which links the learning with performance,

- learning traps which hinder organisation’s success,

- learning facilitators (culture, strategy, structure, environment, organisational life stage, and availability of resources),

- premature learning which can result in organisations with insufficient experience applying inappropriate generalizations to future operations, and temporal and spatial boundaries to learning.

Organisational learning capability and how to measure it: The Organisational Learning Survey

Learning capability can be described as the concept that consists of managerial practices, mechanisms, and management structures that can be implemented to promote learning in an organisation (Goh, Elliott & Quon, 2012). Studies that examine the relationship between organisational learning and performance use measures in forms of survey-type instruments developed to capture learning capability. These measures are then linked to a set of performance measures.

Goh & Richards (1997) developed a 21-item survey to measure the learning capability of organisations using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. This Organisational Learning Survey enables organisations to diagnose the extent to which they embrace the principles of organisational learning. To date, the survey has been applied in a variety of organisations at different staff levels, and it has demonstrated solid psychometric properties and a reliability of .91 as measured by Cronbach alpha (a measure of internal consistency which is an indicator of the quality of scientific studies).

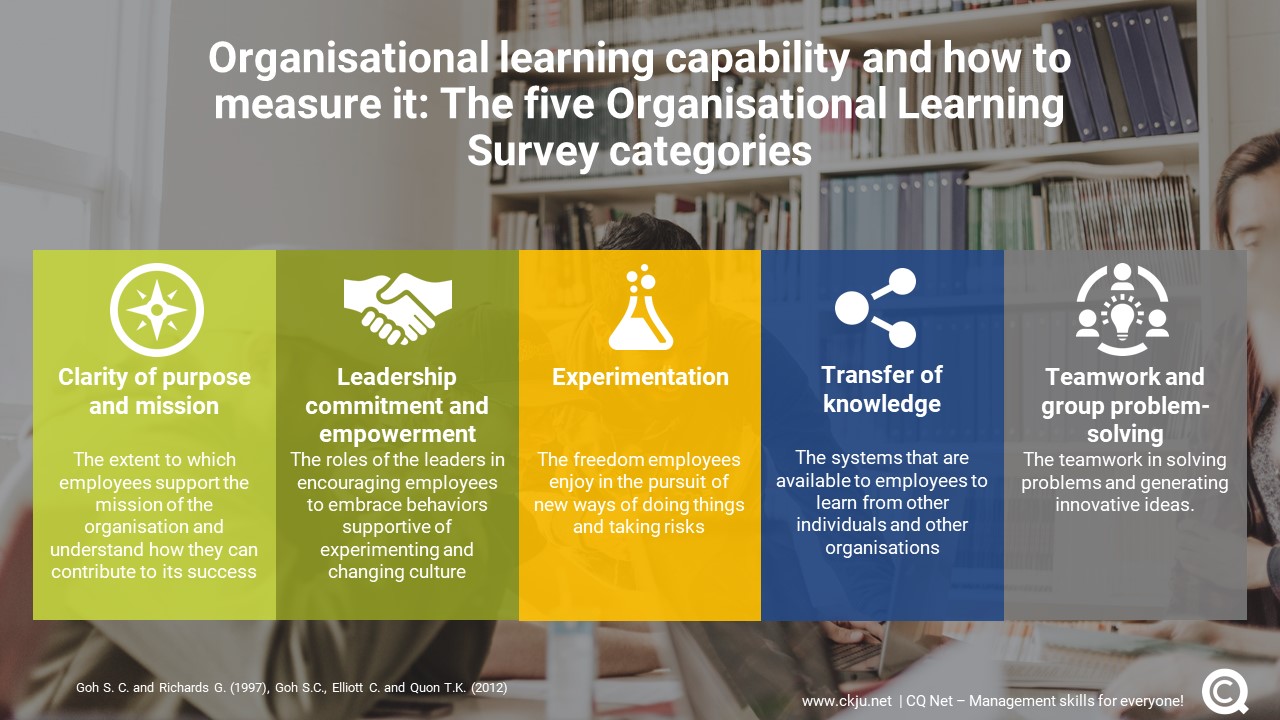

The authors identify five underlying categories that facilitate organisational learning in order to measure the learning capability. These five interdependent and mutually supportive categories are:

- Clarity of purpose and mission: The extent to which employees support the mission of the organisation and understand how they can contribute to its success;

- Leadership commitment and empowerment: The roles of the leaders in encouraging employees to embrace behaviors supportive of experimenting and changing culture;

- Experimentation: The freedom employees enjoy in the pursuit of new ways of doing things and taking risks;

- Transfer of knowledge: The systems that are available to employees to learn from other individuals and other organisations;

- Teamwork and group problem-solving: The teamwork in solving problems and generating innovative ideas.

These five categories already provide a good indication of which practices do foster organisational learning in practice.

What are the benefits of organisational learning?

Despite the explosive growth in the literature, before 1996, there was no empirical work that measured the learning capability and the relationship between organisational learning and performance. Since then, there has been a growing body of empirical research.

But the initial literature was non-conclusive regarding the question of whether there is a positive relationship between learning capability and financial performance. Also, there appeared to be no consensus on a consistent measure of organisational performance as it relates to learning capability since a plethora of measures were included in the studies, ranging from

- objective financial measures such as return on investment (ROI) and return on assets (ROA);

- perceptual measures such as profitability, productivity, flexibility/adaptability, competitiveness, and innovation; and,

- in some cases, a mix of both financial and non-financial measures (Panayides, 2007).

Goh, Elliott & Quon (2012) conducted a meta-analysis of these studies to explore whether there is significant empirical evidence of a link between learning capability and organisational performance, both financial and non-financial. The study is essential, as it attempts to answer a vital question with both conceptual and practical implications: Does developing a learning organisation lead to improved organisational performance and effectiveness?

The meta-analysis shows that empirical research documents that there is a significant positive relationship between learning capability and both financial and non-financial performance. Among the latter, innovation and job satisfaction have the highest correlation with learning capability.

How to foster organisational learning?

Findings of this meta-analysis have significant practical implications as they provide managers and professionals with a concrete approach to building a learning capability by:

- helping them build a stronger case for investing resources into improving the organisational learning capability as these findings clearly document that learning brings benefits;

- developing diagnostic tools they can use to assess an organisation’s learning capability, enabling them to benchmark their organisations and identify practices and resources that are needed to build a stronger learning capability (Goh, Elliott & Quon, 2012).

Albeit the present lack of unified views about almost any concept in the field, the empirical literature did reach convergence in the set of areas that make the foundation of a learning organisation. These four essential areas are in line with the five organisational learning survey categories:

- a shared vision of the organisation and the way it relates to the work of groups and individuals,

- a focus on group work and group problem-solving,

- a culture that fosters experimentation and innovative thinking, and

- the ability to share and transfer knowledge throughout the organisation

Leadership is seen as an all-encompassing concept that plays a crucial role in facilitating, rewarding, and encouraging the four building blocks of a learning organisation.

How to improve organizational learning in practice

Having gone throught the fundamentals of organizational learning, the questions arises how to foster it in practice. We have collected a set of evidence-based practices that help you to develop your organization into the right direction.

Have a clearly communicated purpose

First, both the organisation and each unit within it, need to have a clearly communicated purpose which employees need to understand as well as how they contribute to its achievement. The organisation needs to promote employee commitment to these goals (Goh & Richards, 1998). As stated by Senge (1990, 1992), 'building a shared vision' creates tension as employees see the gap between the vision and the existing state, which leads to learning because they strive to overcome that gap.

Collaborate to accomplish organisational objectives

Second, in today's complex world, individuals need to collaborate to accomplish organisational objectives, and this must be reflected in structures and systems of the organisation. This way, knowledge can be shared across the organisation, enabling its better transfer. Cross-functional teams are also needed, and their lower dependency on upper management should be encouraged (Senge, 1990, 1992).

Frame problems as opportunities for experimentation

Third, problems faced by organisations present opportunities for experimentation, which should be supported by their structure and systems such as budgeting and compensation systems (Senge, 1990; Pedler, Boydell & Burgoyne, 2006).

Focus on effective and efficient communication

Fourth, communication needs to be relevant, clear, fast, and focused, crossing external, functional, and sub-unit boundaries within the organisation. (Shaw and Perkins,1991; Pedler, Boydell and Burgoyne, 2006).

Leaders are pivotal in fostering a learning environment

These are management practices that are important for building learning organisations. Managers and professionals need to be committed to the accomplishment of organisational goals and the goal of learning, creating a climate of meritocracy, and trust where people are approachable and failures are viewed as a part of the learning process.

Leaders need to help detect performance gaps and then help define goals that encourage the acquisition of knowledge that will bridge the performance gaps. Leaders are pivotal in fostering a learning environment through their stimulating behaviour, such as requesting feedback, being open to criticisms, owning up to mistakes, and empowering their employees to make decisions and take risks (Garvin, 1993; Slocum, McGill and Lei, 1994).

Critical appraisal of organisational learning: Solidity Level 3

Even though the concept of organisational learning has been around for many years, the empirical evidence whether it really has a positive impact on organizational performance is rather weak. We found just one meta-analysis that supports the claim that organizational learning has a positive impact on a variety of performance outcomes. As a consequence, we assign a level 3 rating (based on a 1- 5 measurement scale) to available evidence supporting the concept of organizational learning. A level 3 is the third highest rating for a CQ Dossier and the evidence provided on the efficacy of a construct.

Key take-aways

- Despite the increasing popularity of organisational learning and the explosive growth in literature, the concept remains elusive for professionals and managers

- However, first meta-analysis of studies does document that there exists a positive relationship between organisational learning and organisational performance

- The research findings emphasize four practical pillars of organisational learning: shared vision, teamwork, knowledge transfer and experimentation and innovation

- Leadership plays an important role as well with focus on encouraging meritocracy, openness and a safe environment for innovation

References and further reading

Bapuji, Hari & Crossan, Mary. (2004). From Questions to Answers: Reviewing Organizational Learning Research. Management Learning. 35. 397-417. 10.1177/1350507604048270.

Cyert, R. M. & March, J. G. (1963). A Behavioural Theory of Firm. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Friedman, V., Lipshitz, R., & Overmeer, W. (2001). Creating Conditions for Organizational

Learning. In M. Dierkes, A. Berthoin-Antal, J. Child, & I. Nonaka (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Learning (pp. 757-774). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Friedman, V. J., Lipshitz, R., & Popper, M. (2005). The Mystification of Organizational Learning. Journal of Management Inquiry, 14(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492604273758(link is external)

Goh S.C., Elliott C. and Quon T.K. (2012). The Relationship Between Learning Capability and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analytic Examination. The Learning Organization Vol. 19 No. 2.

Goh S. C. and Richards G. (1997). Benchmarking the Learning Capability of Organizations. European Management. Journal Vol. 15, No. 5.

Karatas - Özkan M. and Murphy W.D. (2010). Critical Theorist, Postmodernist and Social Constructionist Paradigms in Organizational Analysis: A Paradigmatic Review of Organizational Learning Literature. International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 12

Panayides P. (2007). The Impact of Organizational Learning on Relationship Orientation, Logistics Service Effectiveness and Performance. Industrial Marketing Management 36. 68-80. 10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.07.001.

Pedler M., Boydell T and Burgoyne J. (2006). The Learning Company. Studies in Continuing Education. 11. 91-101. 10.1080/0158037890110201.

Senge P. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday

Senge P. (1992). Mental Models. Planning Review, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 4-44. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb054349(link is external)

Shaw R.B. and Perkins, D.N.T. (1991). The Learning Organization: Teaching Organizations to Learn. Organization Development Journal, 9 (4), 1-12.

About the Author