- All Management Learning Resources

- organizational resilience

Executive summary

Currently, the world is dealing with the outbreak of COVID-19, a deadly pandemic that is negatively influencing our social and business world. Despite the negative effects of this pandemic, there is much to learn about how professionals and organizations can effectively weather the storm during a crisis such as this. This CQ Dossier provides an overview of the topic of organizational resilience through providing a definition of organizational resilience and describes how organizational resilience is related to success. We will consider why some organizations are more resilient than others and offer recommendations on how organizations can best harness resilience through their employees.

Contents

- Executive summary

- What is organizational resilience?

- Organizational resilience is linked to success

- Resilient organizations invest resources during a crisis

- Why are some organizations more resilient than others?

- How can organizations become more resilient?

- Critical appraisal of organizational resilience: Solidity rating 4

- Conclusion

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

What is organizational resilience?

Organizational resilience is “the ability of an organization to anticipate, prepare for, respond and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and prosper.” (Denyer, 2017).

Research on organizational resilience has focused on behaviors that are either defensive or progressive. When organizations adopt defensive strategies, they are attempting to stop negative events from occurring (Denyer, 2017). Contrastingly, organizations that are progressive in their strategies try to make positive events occur through their actions.

Resilient organizations best use progressive and flexible strategies

There has been debate on which types of strategies work best (Denyer, 2017). Although still contentious, a more adaptive approach has emerged from this debate through a focus on adaptive innovation. Several scholars and practitioners propose that organizational resilience occurs when organizations create, invent and discover unknown markets. Organizations can be competitive in the marketplace through being both progressive and flexible (Denyer, 2017).

Organizational resilience is linked to success

The organizations that do well during a crisis and show resilience take precautionary measures so that they are not overwhelmed when a crisis occurs. These precautionary actions can include employee training for dealing with emergencies or the formulation of a continuity plan in case there is a collapse in the economy.

Precautionary measures help overcome failure and withstand disruption

Previous research has found that it is important for organizations to guide against failure yet also to be strategic in recovering from a disruption (Timmerman, 1981). Organizations that are resilient have the ability to be dynamic and also show stability allowing them to continue operations after a major mishap (Woods & Hollnagel, 2006).

Restaurants or hospitals during the Covid-19 crisis exemplify organizational resilience

For example, during COVID19 many restaurants were forced to close their doors after state-wide orders in different countries across the world. However, several restaurants continued to serve food through delivery services or other means. This is an example of resiliency during a difficult period. In an early study of resiliency, Meyer (1982) examined hospitals and found that resilient hospitals responded well to a sudden doctor’s strike and were able to continue effectively during the crisis and restored order.

Resilient organizations invest resources during a crisis

Overall, organizational science suggests that resilient organizations do not restrict resources when dealing with threats to their existence (Gittell, Cameron, Lim & Rivas, 2006). Rather they deploy internal resources so they are able to continue operations after a crisis.

One example of this can be found in the time of the terrorist attacks on 9/11; firms that laid off people due to the attacks found that their relationships with customers were compromised and they found it difficult to regain profitability (Gittell et al., 2006). However, those firms with the largest financial reserves prior to 9/11 were able to return to previous levels of profitability - or even surpass them - without layoffs of staff (Gittell et al., 2006).

Why are some organizations more resilient than others?

The research on organizational resiliency suggests that successful firms are prepared for adversity and yet are also proactive and flexible when encountering a crisis. Resilient firms prepare for difficult situations and show a “generalized capacity to investigate, to learn, and to act, without knowing in advance what one will be called to act upon.” (Wildavsky, 1988).

Resilience stems from preparation, flexibility and appreciation

Another reason why some firms are more resilient than others is that they value their staff. When people make mistakes in the workplace this is not seen as a source of error, but rather an opportunity to learn from the incident and to build resilience (Hollnagel, Woods & Leveson, 2006). This shift in thinking results in an organizational culture that focuses on the observation and containment of problems (Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003).

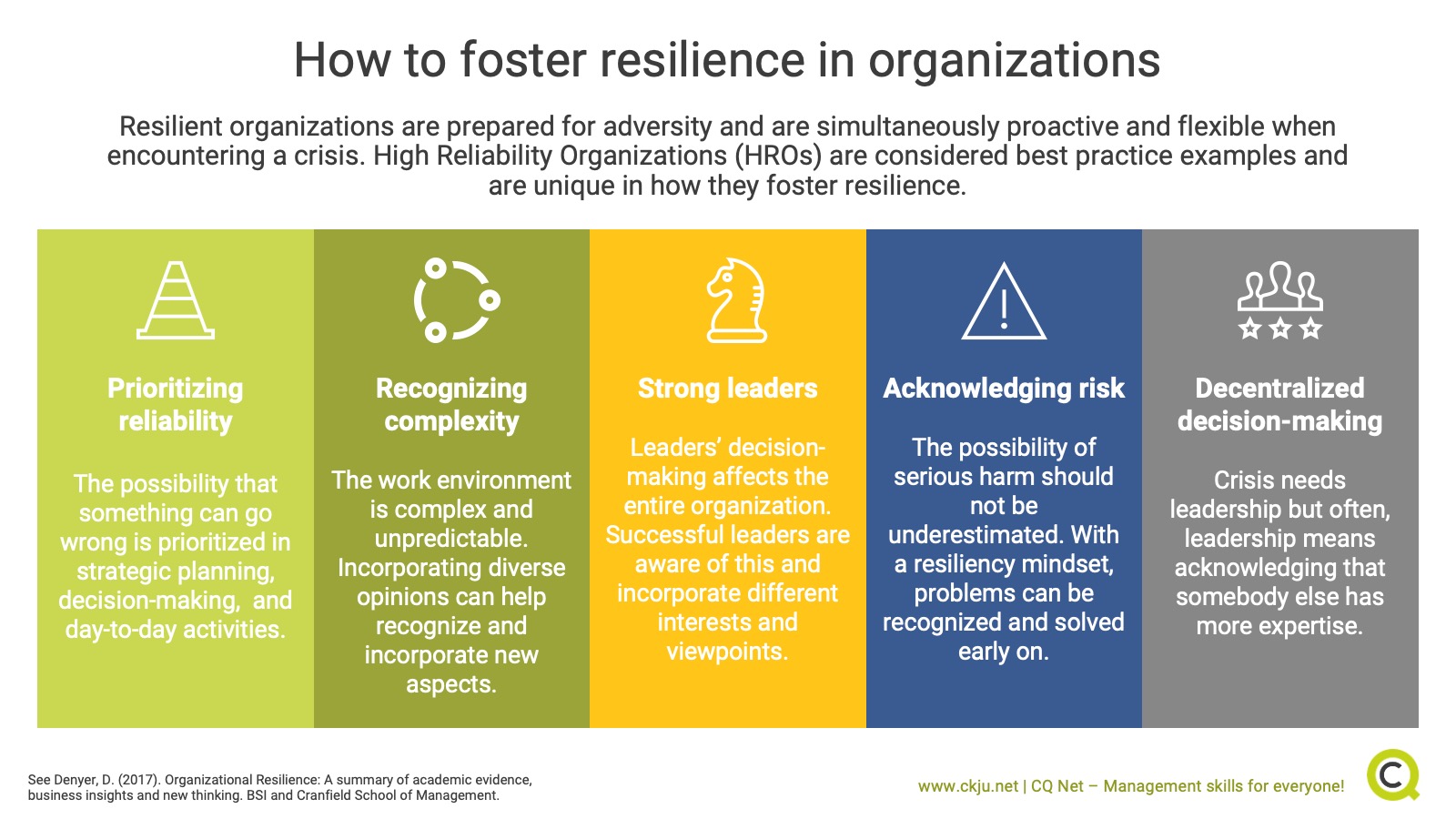

High reliability organizations are more resilient than others

Another reason why some organizations are more resilient than others is because they are highly reliable and efficient in their procedures and practices. Organizational scientists and practitioners refer to these organizations as ‘high reliability organizations.’ (Denyer, 2017) or HROs. HROs such as nuclear facilities, oil and gas companies, and commercial airlines, operate in complex and sometimes dangerous environments so there are many opportunities for failure; however, HROs rarely experience operating failures (Denyer, 2017).

High reliability organizations have a unique way of thinking

Organizational scientists believe the reasons why HROs are so effective is because of the teamwork and cognitive functioning among staff that aims to avoid or mitigate incidents (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007). In particular, HROs engage in mindful organizing.

High reliability organizations (HROs) use five interdependent strategies that foster resilience:

- They prioritize reliability and are sensitive to possible threats. There is a focus on the possibility that something could go wrong (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007)

- They don’t rely on simple interpretations of events. HROs make a deliberate effort to create a complete picture of the work environment. They also encourage diversity in perceptions so that assumptions can be challenged.

- The leadership in HROs is strong and senior management and staff are aware that their decision making can affect the entire organization (Weick & Sutcliffe, 2007).

- HROs show a commitment to a resiliency mindset that recognizing things will go wrong yet can be identified and resolved through a minimization of harm.

- HROs value their staff through recognizing those who are experts and allowing them to make critical decision during a crisis. Senior leaders practice walk around to reinforce behaviors and to help fix critical issues.

How can organizations become more resilient?

There are several human resource practices that are effective in enabling organizations to become resilient.

Individuals are key to fostering organizational resilience

One of the best ways that organizations can foster resiliency is through providing individual training and development of specialized competencies to enhance resiliency (Coutu, 2002). The other way that organizations can foster resiliency is through increasing the motivation and psychological resources of their employees such as self-efficacy, optimism, hope and resiliency (Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003).

Organizations can accomplish this through giving employees task autonomy and discretion because this builds a sense of self-efficacy and competence (Sutcliffe & Vogus, 2003). This boost of confidence can enable employees to respond well during challenging situations such as COVID19 (Masten & Reed, 2002).

Critical appraisal of organizational resilience: Solidity rating 4

Based on the empirical evidence on organizational resiliency as an important characteristic during a crisis, this CQ Dossier is assigned a Level 4 rating (based on a 1- 5 measurement scale). A level 4 is the second highest rating score for a CQ Dossier, based on the evidence demonstrating that resilience is indeed effective for organizations when dealing with a crisis such as COVID-19. Although more research is needed on how resilient organizations cope during a crisis, there is a trajectory of research to demonstrate the importance of this characteristic.

Conclusion

The research on organizational resilience shows that it is an important characteristic for organizations because it helps them deal with a crisis such as COVID-19 through preparation, dynamic planning and proactive behavior. Organizations can build resilience through specific training that equips employees with the psychological capital needed to be resilient during difficult times.

Key take-aways

- Resilient organizations anticipate, prepare for, respond and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and prosper

- Organizational resilience occurs when organizations create, invent and discover unknown markets

- It is important for organizations to guide against failure yet also to be strategic in recovering from a disruption

- Resilient organizations do not restrict resources when dealing with threats to their existence

- Successful firms are prepared for adversity and yet are also proactive and flexible when encountering a crisis

- High reliability organizations demonstrate resilience through effective teamwork and cognitive functioning among staff to mitigate disaster

- Providing training to enhance employees’ psychological capital can foster resilience in organizations

References and further reading

Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. Harvard Business Review, 80, 5.

Denyer, D. (2017). Organizational Resilience: A summary of academic evidence, business insights and new thinking. BSI and Cranfield School of Management.

Gittell, J.H., Cameron, K., Lim, S. and Rivas, V. (2006). Relationships, layoffs, and organizational resilience: airline industry responses to September 11. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 42, pp. 300-329.

Hollnagel, E., Woods, D.D. and Leveson, N. (2006). Resilience Engineering – Concepts and Precepts. Ashgate Publishing.

Masten, A.S. and Reed, M.J. (2002). Resilience in development. In C. R. Snyder and S. Lopez (Eds.). Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 74-88). Oxford Uk. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

Meyer, A.D. (1982). Adapting to Environmental Jolts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 27(4), pp. 515-537.

Sutcliffe, K.M. and Vogus, T. J. (2003). ‘Organizing for Resilience’ in K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton and R. E. Quinn (eds) Positive Organizational Scholarship pp. 94-110, San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Timmerman, P. (1981). Vulnerability, Resilience and the Collapse of Society: A Review of Models and Possible Climatic Application, Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Weick, K.E. and Sutcliffe, K.M. (2007). Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty, second edition. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass.

Wildavsky, A. (1988). Searching for Safety. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction Press.

Woods, D. D. and Hollnagel, E. (2006). Joint Cognitive Systems: Patterns in Cognitive Systems Engineering, Boca Raton, FL, Taylor and Francis.

About the Author