- All Management Learning Resources

- change resistance in organizations

Executive summary

Change is an inevitable, all pervasive part of life and organizations need to predict and plan for future changes. People are programmed psychologically to resist change as they prefer status quo and familiar situations, dislike cognitive dissonance, and abhor the unknown. Several antecedents determine the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral impact of change on work and individual outcomes. The work context, change process, and individual factors can determine the degree of resistance faced by a change.

All resistance is not bad as it can force management professionals to anticipate employees’ response to the change, plan change management strategically, and keep the employees in the loop as important stakeholders. We have a look at change resistance, why it is important and how to overcome it in this CQ Dossier.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Organizations need to plan and prepare for change

- What is change resistance?

- Change resistance manifests in emotions, attitudes, and behavior

- What makes people resist change?

- Work context, change process, and individual factors determine resistance to change

- Resistance to change can show a range of negative behaviors

- Resistance may be overhyped as a villain

- Resistance carries its own benefits

- Change management can overcome resistance to change

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

Organizations need to plan and prepare for change

Change is an inevitable and essential part of life and organizations and their management are no different. It is all pervasive and can be seen at the individual, group, organizational, national, and international level. Its pace cannot be predicted; for example, no one could have foreseen that a global pandemic would change everything for people around the world, bringing economic powerhouses crashing to their feet and unifying people across cultures in solidarity.

COVID-19 may have taken everyone by surprise - however, it is still possible to predict most changes based on established procedures, technological know-how, and savvy managerial judgement.

What is change resistance?

The inevitability is not limited to change alone but also to the resistance to it. It is unfair to suppose that employees always respond negatively to all changes, however, people are psychologically programmed to resist any change in status quo.

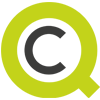

Using a meta-analysis of seventy-nine studies over 60 years, Oreg et al. (2011) created a model to explain resistance. It is adapted here for a simplified understanding: Reactions to change initiatives in organizations are determined based on the causes and the antecedent conditions of the change - this is rooted in organizational culture, support, and the kind of employee profile an organization has along with the planned process, perceived impact, and contents of the change.

The reactions occur at three levels: emotional, cognitive, and behavioral. These reactions, ultimately, translate into the work and personal outcomes.

Change resistance manifests in emotions, attitudes, and behavior

To be fair, any reaction to change manifests through an emotional, cognitive, and hence, behavioral response. However, as seen before, people are psychologically more prone to resist change than to respond positively to it.

Oreg et al.’s (2011) model shows that five pre-existing conditions and causes can influence how employees perceive a change.For instance, any positive change, including a more lucrative incentive scheme will be viewed with suspicion in organizations that do not have a positive culture and where distrust prevails.

Similarly, any change that flouts the principles of distributive justice like the incentives being revised only for the sales department is sure to cause heartburn and resistance. Feelings of being let down, disappointment, doubt, and suspicion will form an adverse opinion against the change and its agents and culminate in resistive behavior.

What makes people resist change?

Psychologists have been interested to know what reasons prompt people to respond negatively to change as early as the late 19th century. Jost (2015) has conducted a systematic literature review of pertinent socio-psychology studies and reported that:

- People prefer tradition and customs over progress (Veblen, 1899)

- People’s habits become reinforced over time with familiarity making them dislike novelty (McDougall, 1908)

- Change forces cognitive dissonance making people avoid new information and seek out the old (Festinger, 1962)

- Change may imply letting go of the existing circle triggering resistance (Hardin and Higgins, 1996)

- Ego, self-interest, a heightened sense of self-worth motivate resistance (Crano, 1995)

- People resist ideas propagated by agents whom they dislike and distrust (Turner, 1991)

- Strength of opposition increases with the expert power of the change agent whom they have rejected (Tormala and Petty, 2004)

- Resistance is high if the proposed change goes against people’ ideological beliefs (Eagly and Kulesa, 1997; Flynn, Nyhan and Reifler, 2017)

- Individual differences determine how people perceive openness, what they consider to be a threat, what mode and frequency of communication they prefer, and their relationship with the agents of change (Erwin and Garman, 2010).

Work context, change process, and individual factors determine resistance to change

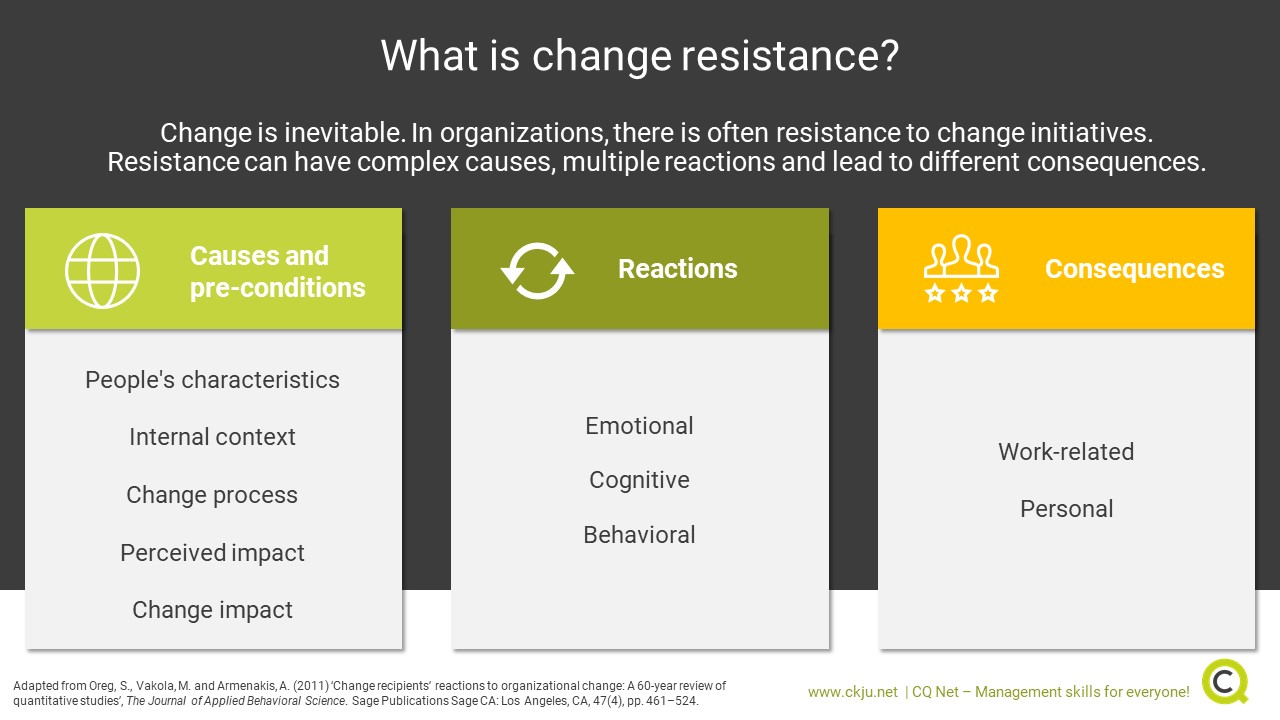

Van Dam et al. (2008)’s model of resistance is simplified for reproduction here:

If the leader-member relationships and the organizational climate are perceived favorably, employees will view the change favorably. If they have trust in the competence and the intention of the management, if the information is shared with them openly and frequently, and if they are involved in the process of planning and implementing change, resistance will be lower.

This is why organizations today invest in identifying and communicating to not only their employees but all high priority stakeholders.

Finally, individual employee’s openness to change and the number of years she has worked with the organization or the team, will also affect how she views the change and her response. However, we have seen that there are far more individual factors that impact how individuals perceive each change.

Resistance to change can show a range of negative behaviors

Negative reactions to change can be seen in explicit behaviors ranging from stress, anxiety, to withdrawal behaviors like the intention to quit the organization (Oreg, Michel and By, 2013; Vakola, Armenakis and Oreg, 2013). In a more immediate reaction, employees may be motivated to resist the change and prevent it from happening by undermining it or flatly opposing it.

Resistance may be overhyped as a villain

There is an interesting angle to the resistance story which proposes that it is not the individual predispositions, rather the acts of the managers as they introduce something new or fail to communicate and involve employees that causes resistance (Ford, Ford and D’Amelio, 2008).

This view is important as it shows that every change may not receive resistance and, in fact, some may even be welcome by employees. It also says that the onus of ensuring that a change is received well lies with the management as it is the organizational culture and trust that play a vital role in the equation.

In fact, Dent & Goldberg (1999) describe it as a bankrupt mental model which turns the organization into a seat of war with the us vs. them mentality. Torrington et al. (2014) assert that people love change and it is wrong to generalize that all people all the time resist change.

Resistance carries its own benefits

Resistance is good as it can show loopholes in the process or in the contents of the change and make its proposers consider it more objectively before its implementation (Ford, Ford and D’Amelio, 2008).

Resistance shows passion which when channeled properly can be leveraged to implement the change more efficiently (Weisbord, 1987). For instance, once the employees are explained the rationale behind a new technological change, their resistance can turn into passion to learn and master it at work.

Resistance to change forces managers to plan change management, to create a strategy to implement it, to communicate with the employees, and to keep their ears to the ground to allay fears and provide support. Without the fear of resistance, organizations will have to suffer extensive losses as managers initiate changes without due planning or reflection.

Change management can overcome resistance to change

There are several models that have sought to use the available knowledge and apply it to overcome resistance and make the change a success. The evidence behind these models varies and it cannot be said for sure to what extent they specifically help understand change resistance, rather than change as a whole.

- Lewin (1951)’s change management model of unfreezing established practices and beliefs, setting up the change, and refreezing the knowledge and beliefs in the new reality is one of the most popular models.

- Lewin (1951) recommended that change agents should recruit and leverage the driving forces for change while controlling or removing the restraining forces.

- Bandura (1986) suggested that change agents should realize that people make conscious choices based on what motivates them and how they perceive the change will facilitate or inhibit their ability to meet their goals. Therefore, change agents need to pay special attention to motivators.

- Eisenstat, Spector and Beer (1990) reported that six steps of realigning tasks by mobilizing commitment, creating a shared vision, building consensus, involving all departments organically, institutionalizing the involvement, and monitoring the strategies can create effective change.

- Thaler and Sunstein (2009)’s nudge theory suggests that small changes and constant encouragement can not only identify the deep-rooted beliefs within people, they can also eliminate the harmful ones and build on the positive ones.

There are many more change management models which can help in understanding what drives change and how it can be made into a success. Successful change agents learn to diagnose the situation and proceed with proper planning.

Key take-aways

- Resistance to change is as inevitable as change itself

- Antecedent conditions can influence the intensity and form of resistance

- Several psychological factors prompt people to resist change

- Managers can and should take effective steps to manage change systematically

- Resistance is good as it forces managers to initiate only those changes that they can justify and implement properly

- Change models can help in understanding the mechanics of change

References and further reading

Bandura, A. (1986) ‘Social foundations of thought and action’, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1986.

Crano, W. D. (1995) ‘Attitude strength and vested interest’, Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences, 4, pp. 131–157.

Van Dam, K., Oreg, S. and Schyns, B. (2008) ‘Daily work contexts and resistance to organisational change: The role of leader–member exchange, development climate, and change process characteristics’, Applied psychology. Wiley Online Library, 57(2), pp. 313–334.

Dent, E. B. and Goldberg, S. G. (1999) ‘Challenging “resistance to change”’, The Journal of applied behavioral science. Sage Publications Sage CA: Thousand Oaks, CA, 35(1), pp. 25–41.

Eagly, A. H. and Kulesa, P. (1997) ‘Attitudes, attitude structure, and resistance to change’, Environmental ethics and behavior, pp. 122–153.

Eisenstat, R., Spector, B. and Beer, M. (1990) ‘Why change programs don’t produce change’, Harvard Business Review, 68(6), pp. 158–166.

Erwin, D. G. and Garman, A. N. (2010) ‘Resistance to organizational change: linking research and practice’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Festinger, L. (1962) A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford university press.

Flynn, D. J., Nyhan, B. and Reifler, J. (2017) ‘The nature and origins of misperceptions: Understanding false and unsupported beliefs about politics’, Political Psychology. Wiley Online Library, 38, pp. 127–150.

Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W. and D’Amelio, A. (2008) ‘Resistance to change: The rest of the story’, Academy of management Review. Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY, 33(2), pp. 362–377.

Hardin, C. D. and Higgins, E. T. (1996) ‘Shared reality: How social verification makes the subjective objective.’ The Guilford Press.

Jost, J. T. (2015) ‘Resistance to change: A social psychological perspective’, Social Research: An International Quarterly. Johns Hopkins University Press, 82(3), pp. 607–636.

Lewin, K. (1951) ‘Field theory in social science’. Harper.

McDougall, W. J. (1908) An introduction to Social Psychology. New York: Luce.

Oreg, S., Michel, A. and By, R. T. (2013) The psychology of organizational change: Viewing change from the employee’s perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Oreg, S., Vakola, M. and Armenakis, A. (2011) ‘Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies’, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 47(4), pp. 461–524.

Peters, T. J., Waterman, R. H. and Jones, I. (1982) ‘In search of excellence: Lessons from America’s best-run companies’. Harper & Row New York.

Thaler, R. H. and Sunstein, C. R. (2009) Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

Tormala, Z. L. and Petty, R. E. (2004) ‘Source credibility and attitude certainty: A metacognitive analysis of resistance to persuasion’, Journal of Consumer Psychology. Wiley Online Library, 14(4), pp. 427–442.

Torrington, D., Hall, L. and Taylor, S. (2014) ‘Human Resource Management’, in Human Resource Management, pp. 440–441. Available at: http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/7920/.

Turner, J. C. (1991) Social Influence. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Vakola, M., Armenakis, A. and Oreg, S. (2013) ‘Reactions to organizational change from an individual differences perspective: A review of empirical research’, The psychology of organizational change: Viewing change from the employee’s perspective. Cambridge University Press New York, pp. 95–122.

Veblen, T. (1899) The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. New York: Heubsch.

Weisbord, M. R. (1987) Productive workplaces: Organizing and managing for dignity, meaning and community. Jossey-Bass.

About the Author