- All Management Learning Resources

- Change management models

Executive summary

Organizations must often change their practices, outlook or norms to improve, innovate, and stay competitive in VUCA world. There are plenty of change management models that promise a framework for implementing major changes in organizations. From Kotter’s ‘8 step Model’, McKinsey's ‘7-S model’ to Lewin's ‘unfreeze, change and refreeze’ model - all these frameworks claim, in one way or another, to be the best way to make sense of and implement change and innovation initiatives. What assumptions are behind these models and do the traditional, famous models really hold up? In this dossier, we take a critical look at traditional change management models and introduce you to some alternatives that can help implement change successfully.

Contents

- Executive summary

- Change models reflect assumptions about how organizations work

- Traditional change models are linear frameworks: X leads to Y

- Traditional change management focuses on the role of senior management

- Organizational dynamics are changing and change models should reflect this

- Change is an ongoing process involving multiple actors

- Strategy as practice: strategy seeps through every aspect of an organization

- Emergent change theory: change emerges from below and is a continuous process

- Chaos theory: systems are dynamic by design and unpredictable

- Nudging: subtle changes in behavior can lead to major adaptation

- Change and communication: How to manage change with discourses

- Alternative change management theories help step outside the box and yield new results

- Conclusion

- Key take-aways

- References and further reading

Change models reflect assumptions about how organizations work

Change management can be defined as seeking to improve an “organization’s direction, structure and capabilities to serve the ever-changing needs of external and internal customers” (Moran and Brightman, 2001, p.111). Organizational change is vital in operational and strategic terms and is intimately linked to organizational strategy (see By, 2005). However, the way in which change is conceived is deeply-reflective of assumptions about organizations. These assumptions, in turn, determine what will be possible to conceive and to achieve. Therefore, it makes sense to scrutinize the models commonly used and to ask whether using them truly leads to the best-possible change interventions and innovation scenarios.

Traditional change models are linear frameworks: X leads to Y

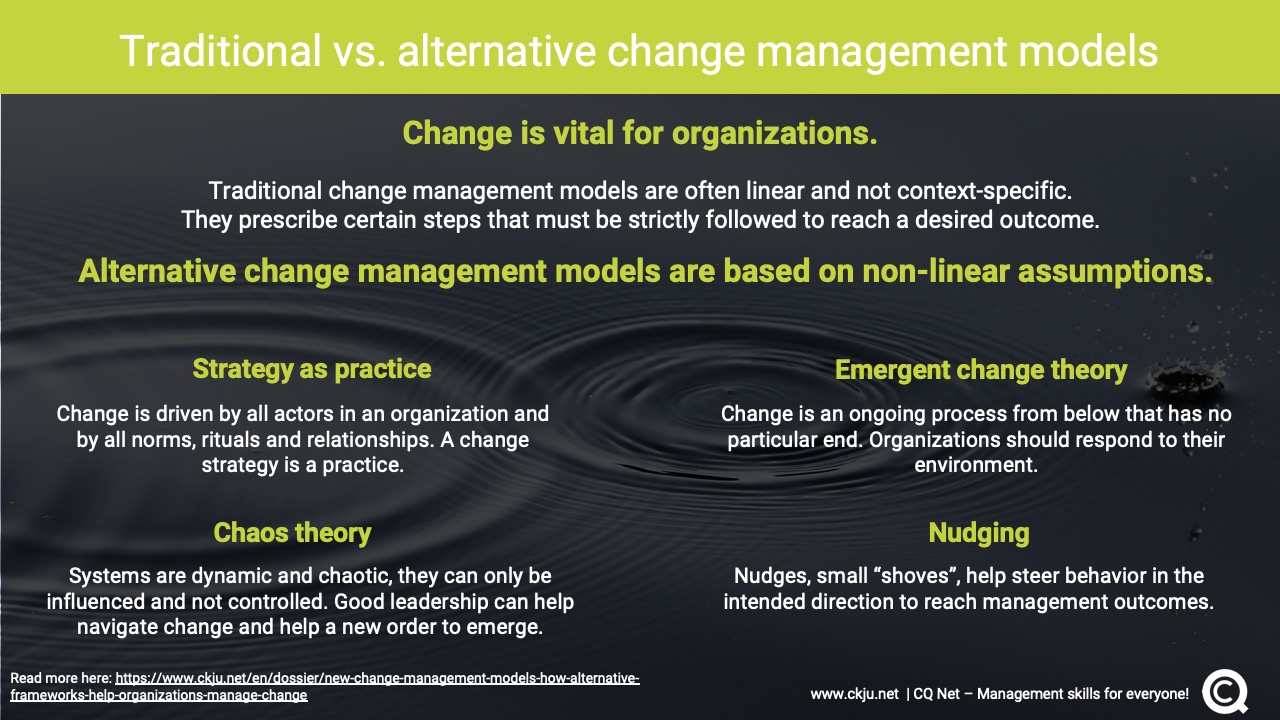

In organizational development, the majority of change models prescribe a series of steps that organizations need to complete in order to implement change or innovations (Graetz & Smith, 2010). Most traditional models indeed consider change to be a step-by-step process that applies to organizations regardless of context or individual situation.

To give an example: John Kotter’s 8 step Model encourages change agents to:

- increase urgency;

- build guiding team;

- develop a vision;

- communicate for buy-in;

- empower action;

- create short term wins;

- be persistent and

- make change permanent.

Kotter (1996) states that these steps should be completed in a linear fashion and to skip steps will not produce a satisfactory result. Kotter also advises against making mistakes in any of the phases and warns that this will slow momentum and negate previous gains (Kotter, 1996).

Similarly, Luecke’s 7 step Model prescribes three steps:

- the mobilization of energy and commitment

- developing a shared vision

- identifying leadership to enact the change (Luecke, 2003).

Both Kotter (1996) and Luecke (2003) state that these steps should be completed in a linear fashion and to skip steps will not produce a satisfactory result. For change to be successful, these steps should be followed strictly with no mistakes as this would slow momentum.

Traditional change management focuses on the role of senior management

At the center of these classical models is a focus on senior management demonstrating effective leadership behaviors, such as showing charisma through emotional language and being role models for vision and change (Graetz & Smith, 2010). From a logical and linear perspective, these models seem ideal in that they provide organizations and change agents with a template of prescribed steps to enact innovation and increase openness to change within the organization. However, the empirical research to support these linear approaches is weak.

In a recent meta-analytic review, Jones et al. (2019) analyzed 200 organizational change case studies. They found that the majority of change initiatives used traditional change models with a particular focus on Kotter’s Eight Steps model. However, although some of the initiatives were successful, there were failures: On the one hand, change initiatives did not succeed because the steps were not followed properly.

On the other hand, they sometimes succeeded but even without following the mode. In addition, although most change models suggest that strong leadership is needed for organizational change, there is little empirical evidence to support this notion (Parry, 2011) and in Jones et al.’s study, change did not work despite the best leadership models were implemented. Such findings challenge the effectiveness of such models and raise the question of whether they can be successful in the first place.

Organizational dynamics are changing and change models should reflect this

There is an ongoing debate among scholars as to whether management practices need to stay the same, shift, or be re-invented altogether to stay up-to-date with current advancements and developments in the VUCA world. As such, there has been discussion about new practices and norms that are emerging. These call for a new view of organizations as such: organizational design is changing, hierarchical management models are becoming increasingly outdated and classical leader-follower relationships are changing.

In a study with business executives on the differences between the traditional and digital environment, Kane et al. (2017) find that agility and the ability to experiment are crucial for organizational survival. With such considerable changes in the business environment and in organizational practice per se, there is also an increased need for new frameworks that take into account this nature. In particular change management models, that serve the very purpose of helping organizations to best implement innovations, must therefore step away from the way that business has been done until now (see Felin and Powell, 2016).

Change is an ongoing process involving multiple actors

Beyond the traditional focus on linearity and controllability, there are several noteworthy traditions and streams in literature that showcase alternative and less strict models of fostering change and innovation. These are built on the underlying assumption that change management is a continuous process of improvement (see Moran and Brightman, 2001).

Strategy as practice: strategy seeps through every aspect of an organization

In the strategy as practice (SAP) approach, the underlying assumption is that strategy, which is usually confined to top management only, is not a dominant top-down procedure but rather an ongoing practice that permeates an organization in all aspects. SAP-based change management initiatives posit that it is the discourse in an organization that enables, develops and implements strategic objectives (Golsorkhi et al., 2010). In other words, it is the norms and rituals in organizations that influence change. These must be constantly re-evaluated and re-aligned to achieve the desired outcome.

In order for change management to be successful, it is therefore necessary to conceive change on the structural level and to implement it on the instrumental level, i.e. in relationships, language, communication, expression, work ethic, and so on (see Hendry, 2000). As such, SAP is an approach that considers organizations as evolving entities that are in a continued process of change and growth (Whittington, 1996).

Emergent change theory: change emerges from below and is a continuous process

The theory of emergent change suggests that change is a continuous process with an open, unpredictable end, in which organizations respond proactively to environmental stimuli (Burnes, 2004). Traditional and planned change efforts often focus on diminishing restrictive environmental forces and remedying them - emergent change efforts take a different approach and focus on identifying the enabling forces and enhancing them (Livene-Tarandech and Bartunek, 2009:13). In this vein, change is conceived as coming from the bottom-up, rather than the top-down (Bamford & Forrester, 2003).

Successful change interventions occur when organizations gain understanding of the complex dynamics affecting them and identify the range of solutions to address the problem; too much focus on detailed plans and projections can erode the implementation of a successful organizational change initiative (Burnes, 2004).There are several benefits to employing a change model based on emergent change theory: emergent change is sustainable due to its sensitivity to local contingencies, it helps manage needs of autonomy, control and expression, and it helps make use of tacit knowledge (see Weick, 2000 in Liebhart and Lorenzo, 2010).

Chaos theory: systems are dynamic by design and unpredictable

One of the most influential theories of organizational development is chaos theory, which also acknowledges that change is not a linear process. In change theory, there are multiple factors - both internal and external - that influence organizations. Systems are dynamic (and chaotic) by design and characterized by the social relationships within them (Levy, 1994). Therefore, no forecasts on impact can be made and no outcomes of initiatives could ever be predicted or replicated (Thietart and Forgues, 1995).

Given the complexity of workplace dynamics, it is important to realize that traditional linear models fall short of providing an adequate narrative of how change influences organizations in day-to-day work. This is an advantage of chaos theory: it is reflective of daily realities. However, this also means that in the context of change management, one needs to understand organizations cannot be controlled but only influenced. As such, change management in this theory requires faith and trust that the organization and actors within it to some extent can regulate itself, with the help of guidance from leadership. Smith & Humphries (2004) state that this will allow for the emergence of a new order based on self-organization.

Nudging: subtle changes in behavior can lead to major adaptation

Contrasting the above-mentioned change management frameworks, nudging is an approach that is not open ended but goal-oriented. Nudging originally comes from behavioral economics and refers to the use of subtle “pushes” to behavior that lead to a desired outcome. These pushes (=nudges) are based on human heuristics, so patterns in human behavior that can be made use of for certain ends. For example, providing open spaces in an office can lead to employees being more productive and innovative as there is more room to think, and less pressure to deliver.

When it comes to change management as a broader initiative, Ebert and Freibichler (2017), the major proponents of nudging for management, point out that nudge management is not intrusive - rather, it is easily scalable, and employees are not forced to make changes to their working habits. The entire process is more subtle. However, just as nudging has its benefits, it has also been critiqued for providing room for abuse and unethical behavior. In addition, not all people respond equally to nudges, (Benkert and Netzer, 2018) meaning that nudging is probably best used as a supplementary tool to more all-encompassing change management initiatives.

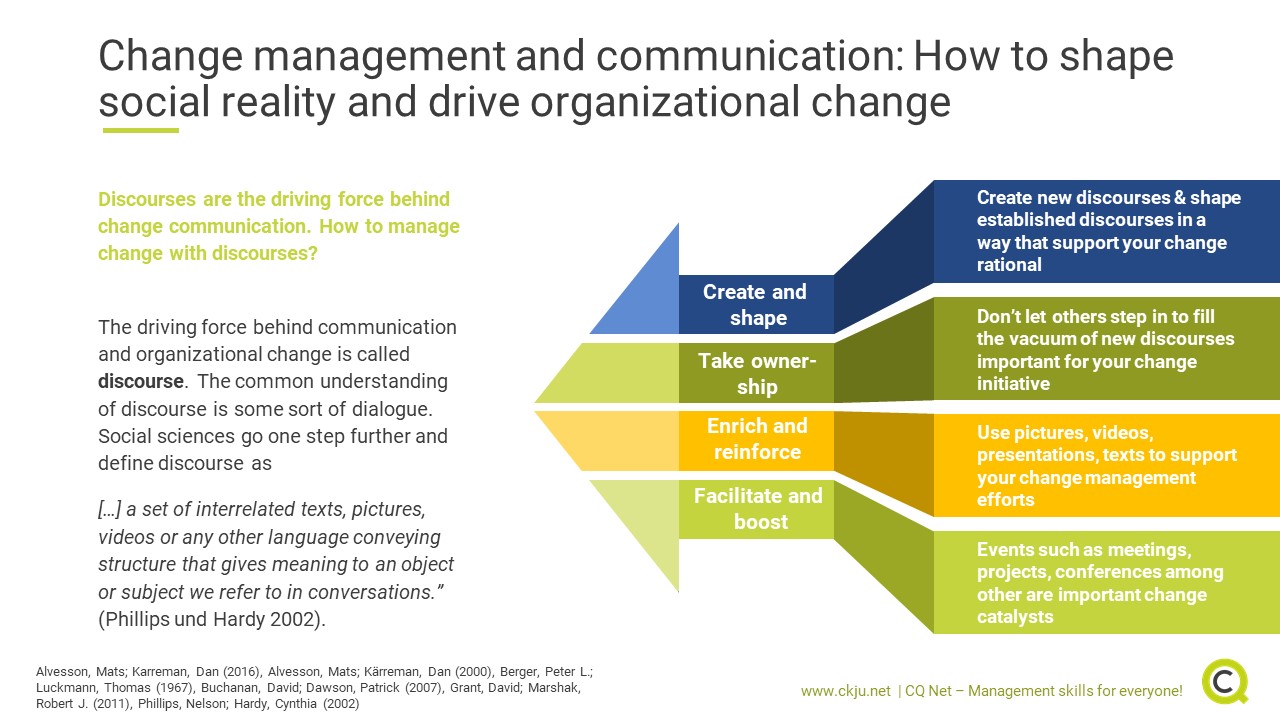

Change and communication: How to manage change with discourses

Another alternative change management model emphasizes the role communication and language plays in driving and inhibiting change. The underlying assumption of "discourse-based change management" is that social reality is not static but constructed by communication and language use. Once social reality changes, people adjust their behavior in a way such that newly introduced norms, expectations, cultural values and power relationships are met.

The theoretical foundation of this change mangement model goes back to social constructivism (e.g. Berger und Luckmann 1967). It states that communication is the driving force behind institutionalization which is when newly introduced discourses start to be taken for granted. As with most alternative change management models, discourse-based change management assumes that change cannot be managed in a linear, controlled and top-down manner. Instead, it emphasizes that communication is an important lever to manage change and that this lever is not just available to a specific group of people but to almost anyone.

Alternative change management theories help step outside the box and yield new results

The alternative theories outlined above have in common that change is not a static concept that is implemented from the top to achieve a certain result. Rather, they all assume that change is a gradual process that is characterized by many actors and instrumental factors that often cannot be controlled. In the words of Graetz and Smith (2010, p.136),

“[...] understanding change as part of a continuing work in progress calls for a much broader canvas that seeks out competing voices, and works with the resulting ambiguities, contradictions and tensions of messy reality”.

Considering that many organizations still favor strict planning and hierarchical relationships as a manner to conduct business, it makes sense to keep in mind that there are other ways to achieve results. In particular the context of the VUCA world raises the need for flexibility and adaptability not only in mission outlook, but also daily practice. Scientifically, this is slowly emerging: By (2005) points out that there is no existing measurement tool for change management in the ways mentioned in this article. A new, dynamic tool would help carry out empirical studies and help make conclusions on the success or failure of change interventions that take into account the dynamic nature of change.

Conclusion

Organizations must evolve and adapt in an increasingly complex environment. Unfortunately, traditional models are outdated in prescribing remedies to deal with change in a ways that are truly effective and all-encompassing. One of the issues of traditional change programs, for which research exists, is the lack of success: around 70% of change initiatives fail to produce success. This is because there is a lack of an effective frameworks that enable organizations to implement and manage organizational change on their own terms and in their own specific environment and situation (Burnes, 2004).

Rather, the most successful innovations occur when organizations are prepared to deal with external and internal events through constantly evaluating and monitoring the environment (Burnes, 2004), and remaining flexible and experimental in their responses. As such, it makes sense to consider alternative approaches and the underlying assumptions to determine on a case-by-case basis which change management model is the most lucrative.

Key take-aways

- Traditional change management models are often linear and not context-specific

- The VUCA world requires organizations to adapt and to remain flexible

- Alternative change management models have completely different underlying assumptions about organizations

- Strategy as practice conceives strategy to be bottom-up and to be implemented in every aspect of the organization, from communication to rituals and norms, to standardized work processes.

- Emergent change theory considers change to be open-ended and to best be managed by reacting to new stimuli proactively

- Chaos theory assumes systems are inherently chaotic and unpredictable. Chaos should be embraced and change is carried by everyone and cannot be controlled, only influenced

- Nudging for management focuses on subtly altering behavior by providing an environment that leads people to act in a desired way, thereby culminating in change.

- Change management is vital and alternative theories enable new opportunities, visions and actions

References and further reading

Bamford, D. R., & Forrester, P. L. (2003). Managing planned and emergent change within an operations management environment. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 23, 546-564.

Benkert, J. M. and Netzer, N. (2018). Informational Requirements of Nudging. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 126 No. 6, pp 2323.

Berger, Peter L.; Luckmann, Thomas (1967): The Social Construction of Reality. A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Random House.

Burnes, B. (2004). Emergent change and planned change – competitors of Allies? International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 24, 9, 886-902.

By, T. R. (2005) Organisational change management: A critical review, Journal of Change Management, 5:4, 369-380.

Ebert, P. and Freibichler, W. (2017). Nudge Management: applying behavioural science to increase knowledge worker productivity. Journal of Organization Design, Vol. 6 No. 4.

Felin and Powell (2016) Designing organizations for dynamic capabilities. in Cousins, B. (2018) Design Thinking: Organizational Learning in VUCA Environments. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17 No. 2.

G.C. Kane, D. Palmer, A.N. Phillips, D. Kiron, and N. Buckley (2017). Achieving Digital Maturity. MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte University Press, July 2017.

Goh S.C., Elliott C. and Quon T.K. (2012). The Relationship Between Learning Capability and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analytic Examination. The Learning Organization Vol. 19 No. 2.

Golsorkhi, D., Rouleau, L., Seidl, D. & Vaara, E. (Eds.) (2010). Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graetz, F., & Smith, A. (2010). Managing Organizational Change: A philosophies of Change Approach. Journal of Change Management, 10, 2, 135-154.

Hendry, J. (2000), Strategic Decision Mking, Discourse, And Strategy As Social Practice. Journal of Management Studies, 37: 955-978.

Jones, J., Firth, J., Hannibal, C., & Ogunseyin, M. (2019). Factors Contributing to Organizational Change Success or Failure: A Qualitative Meta-Analysis of 200 Reflective Case Studies. Evidence-Based Initiatives for Organizational Change and Development.

Levy, D. (1994). Chaos theory and strategy: Theory, application, and managerial implications. Strategic Management Journal, 15, 167-178.

Livne-Tarandach, R. & Bartunek,J. (2009) ‘A new horizon for organizational change and development scholarship: Connecting planned and emergent change’ In: Woodman, R; Pasmore, W. & Shani A. (Eds) Research in Organizational Change & Development, 17. Bingley: Emeral Group Publishing Ltd.

Luecke, R. (2003). Managing Change and Transition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Moran, J. W. and Brightman, B. K. (2001) ‘Leading organizational change’, Career Development International, 6(2), 111 –118.

Parry, K. W. (2011). Leadership and organization theory. In A. Bryman, D. Collinson, K. Grint, B. Jackson, & M. Uhl-Bien (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Leadership, 53-70. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd.

Smith, A. & Humphries, C. (2004). Complexity theory as a practical management tool: A critical evaluation. Organization Management Journal, 1(2), 91-106.

Thietart, R. A., & Forgues, B. (1995). Chaos theory and organization. Organization Science, 6, 19-31.

Weick, K. E. (2000) Emergent change as universal in organizations in Liebhart, Margrit and Garcia-Lorenzo, Lucia (2010) Between planned and emergent change: decision maker’s perceptions of managing change in organisations. International journal of knowledge, culture and change management, 10 (5), 214-225.

Whittington, R. (1996) Strategy as practice, Long Range Planning, 29(5), 731–735.

About the Author